Last Updated on April 9, 2024 by BVN

Breanna Reeves | Photos by Aryana Noroozi

In recognition of the advocacy and efforts of the J.W. Vines Medical Society, the University of California, Riverside (UCR) renamed their annual Diversity Equity and Inclusion Colloquium to the UCR School of Medicine’s J.W. Vines Diversity Equity and Inclusion Colloquium. The J.W. Vines Medical Society is a nonprofit organization that supports Black physicians and medical students across the Inland Empire with mentoring and educational opportunities.

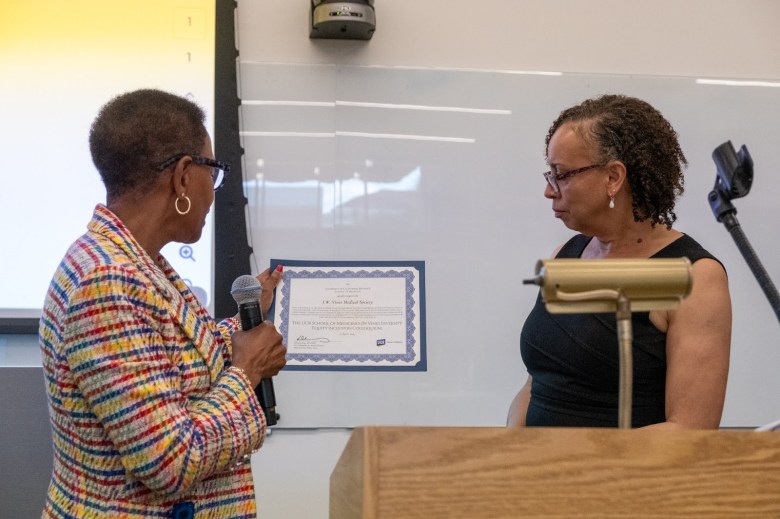

“This important recognition will ensure that the story and legacy of these important contributions are a part of our history and are woven into our ongoing work far into the future,” said Dr. Deborah Deas, Dean of UCR’s School of Medicine. Dr. Deas presented the certificate to current J.W. Vines Medical Society President Dr. Leita Harris during a UCR event celebrating the society’s impact on the School of Medicine.

This certificate is one of the many accolades awarded to the J.W. Vines Medical Society over the course of its history. UCR hosted a celebration, honoring the society for their efforts and contributions to the School of Medicine and forging a pathway for Black students and other students of color who were systematically eliminated from the school’s biomedical division.

Here’s a timeline of how the Vines Society’s dedication to supporting the advancement and success of Black medical students made a lasting impact on the community and UCR’s School of Medicine.

1974

In July, UCR’s Division of Biomedical Sciences launches after receiving approval from Gov. Jerry Brown. The program initiated the idea of establishing a medical school on the campus. The division is jointly operated by UCR and University of California, Los Angeles’s (UCLA) Program in Biomedical Sciences, a seven-year accelerated Bachelor of Science/MD program.

Initially, UCR’s Division of Biomedical Sciences set out to admit as many high scoring students to the program to improve and increase undergraduate enrollment at the time.

According to Dr. Craig Byus, former dean and program director for the Division of Biomedical Sciences, the program did well and brought in an estimated 200 students per year. Students in the Biomedical Sciences Division had the highest retention rates among any other majors on campus.

Decades later, as the division was in the process of transforming into the School of Medicine, UCR faced challenges with poor administrative leadership, reduced faculty, poor recruitment, inadequate student support resources, and a lack of Black students.

“Now, the Vines Society stepped into this huge leadership vacuum, and they were advocates, but they really stepped into this vacuum. They provided both a needed vision of what the State of California’s Inland Empire needed,” said Dr. Byus. “And they brought the leadership ability to get it accomplished by going to the legislature and getting it done.”

1987

The James Wesley Vines Medical Society Inc. (JWV) is granted a charter to organize as a component society of the National Medical Association and the Golden State Medical Association in the Pomona Valley Area. The first meeting is held in February where Dr. Benjamin G. Vines, an internist, is elected president.

1989

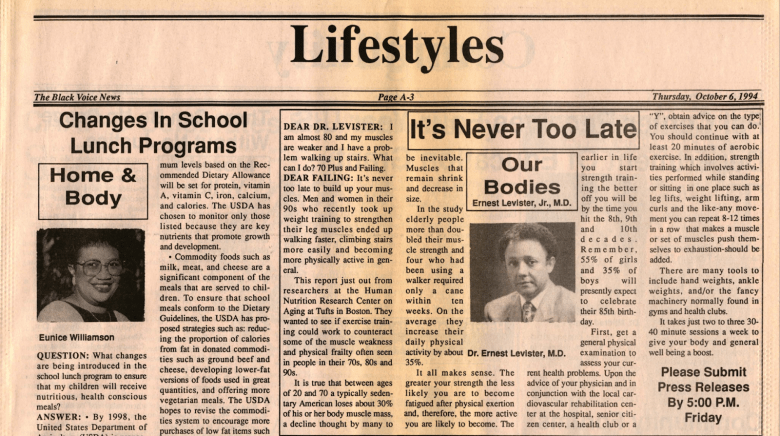

Dr. Vines holds the position of president of the James Wesley Vines Medical Society, Inc. (JWV) until he passed away. Dr. Ernest Levister Jr., a member of the society, serves as a columnist for Black Voice News where he writes weekly articles about a variety of health topics and answers health questions from community members.

1994

Dr. Levister serves as president and the name of the society changes from JWV to James Wesley Vines, Jr. M.D. Medical Society, Inc., a component of the National Medical Association.

1995

The J.W. Vines Medical Society becomes concerned about UCR’s Biomedical Sciences program when they are invited to a campus event hosted by a student organization called African Americans United in Science.

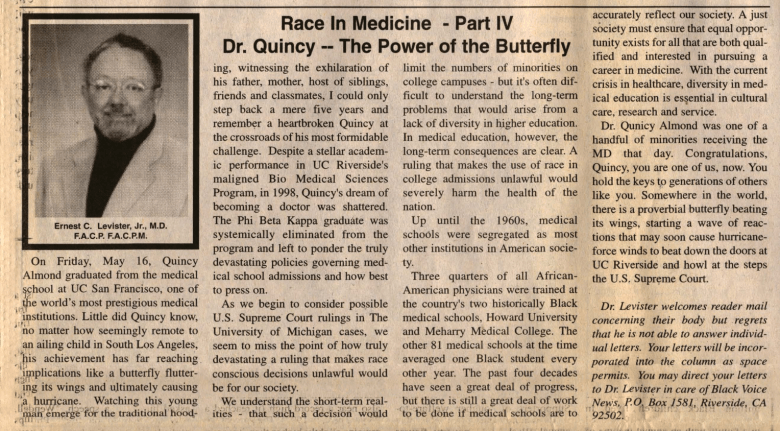

Dr. Levister recalled the event being held in honor of a student, Blake Wilson, who was expected to become the second Black student accepted into the biomedical program in its 28-year history.

“Growing concerns over the low minority selection rate were compounded when Wilson and several other highly qualified students, including Quincy Almond, a junior and Phi Beta Kappa failed to make the final cuts,” Dr. Levister said during his speech at the celebration.

“What I witnessed first hand shook me to the core. And Quincy was one of my mentees, and I cried for and with him.”

The Vines Society repeatedly seeks answers from UCR administration about how highly qualified Black students were “systematically weeded out” of the program and urge them to address the inequity.

“We were repeatedly rebuffed and ignored,” Dr. Levister said.

1997

UCR’s Division of Biomedical Sciences program is renamed the UCR/UCLA Thomas Haider Program in Biomedical Sciences after a gift to the program from Dr. Thomas Haider, a spinal surgeon, and his wife Salma. The Haiders support the establishment of a medical school at UCR and are proponents for admitting underserved students into the program.

2000

“After years of constant broken promises, members of the Vines concluded that UCR’s commitment to changing the program and boosting minority rates were an abject and cascading failure,” Dr. Levister said.

Following this conclusion, the Vines Society wrote a resolution that says they will no longer recommend the program for minority students. They launch a state-wide media campaign and mail the resolution to lawmakers, other medical schools, high school advisors, teachers and major medical societies. They also send letters to the UCLA Chancellor and dean of the medical school.

2001

Members of the Vines Medical Society go to Sacramento to address and meet with lawmakers and the Assembly Budget Subcommittee for Higher Education and Finances.

The J.W. Vines Foundation Inc. is established as a philanthropic component of the James Wesley Vines, Jr. M.D. Medical Society Inc. The Vines Foundation provides mentoring, physician shadowing and support to college students.

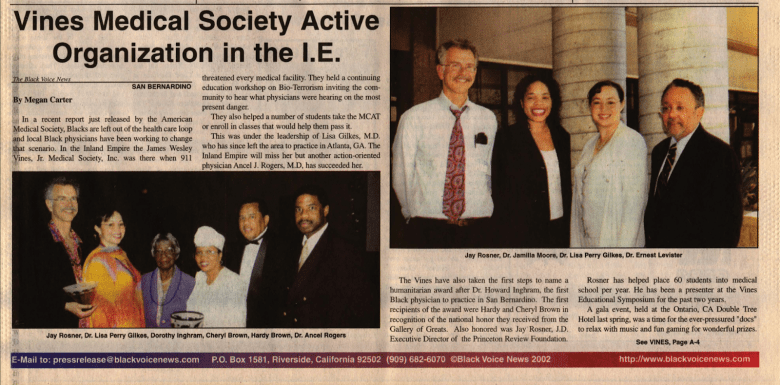

2002

Dr. Levister and the J.W. Vines Medical Society lobbies the California Legislature to mandate structural and curricular changes to the UCR/UCLA Thomas Haider Program that will expand opportunities for underrepresented students to join the program.

“After more than seven years, and help from politicians, local churches, the business community, organizations, health care leaders and members of the greater Inland community, the Vines finally succeeded in forcing change to the UC Riverside biomed program,” Dr. Levinster explained.

The support and advocacy on behalf of the J.W. Vines Medical Society leads to UCR establishing a new mission: “to improve the health of the people of California and, especially, to serve Inland Southern California by training a diverse workforce of physicians.”

Dr. Levister supports the establishment of the student organization, African Americans United in Science. The J.W. Vines Medical Society also supports students with lectures, mentoring, a summer medical enrichment program, and funding for MCAT preparation courses.

“Little known fact is, Dr. Levister actually bought me my first suit,” said Dr. Michael Nduati, former UCR Thomas Haider Program student and current UCR associate clinical professor. Dr. Nduati is now a member of the J.W. Vines Medical Society and was a co-founder of UCR’s African Americans United in Science alongside Dr. Shareece Davis.

2003

The National Medical Association hosts a conference in Indian Wells where members attend Accredited Continuing Medical Education (CME) workshops. The Vines Society leads a workshop where they focus on disparities in medicine and media/legislation.

2005

Dr. Nduati and Dr. Davis are some of the first Black students to graduate from the program in the UCR/UCLA Thomas Haider Program’s 30-year history. According to Dr. Levister, highly qualified African American students are systematically dumped from the program.

“It’s amazing to have the support of a group of local African American physicians and honestly, leaders in the community, that help us [and] support us through,” said Dr. Nduati during the UCR celebration.

“I genuinely believe that myself and other students like myself would not have succeeded without their intervention, because there were many highly qualified African American students before me, who didn’t get selected in the Biomedical Sciences.”

2008

After UCR proposed to establish a School of Medicine in 2006, UC Regents approve UCR’s proposal for a medical school, making it the sixth in the UC system.

2012

Dr. Ancel J. Rogers serves as president of the J.W. Vines Medical Society. In 2011, the school’s initial accreditation was denied due to concerns about the state’s ability to provide funding, but we were granted preliminary accreditation.

In October 2012, after getting alternative funding from private donors, local government and the UC system, the school was granted preliminary accreditation.

2013

The first class of 50 students are welcomed to the UCR School of Medicine for the white coat ceremony.

2023

UCR School of Medicine celebrates its 10 year anniversary. Since first admitting students in 2013, the school has graduated nearly 400 medical doctors. The school also prepared to open Education Building II as part of the School of Medicine.

2024

UCR School of Medicine Dean Dr. Deborah Deas renames their annual Diversity Equity and Inclusion Colloquium to the UCR School of Medicine’s J.W. Vines Diversity Equity and Inclusion Colloquium. The event will be hosted on May 22, 2024.