Last Updated on July 9, 2024 by BVN

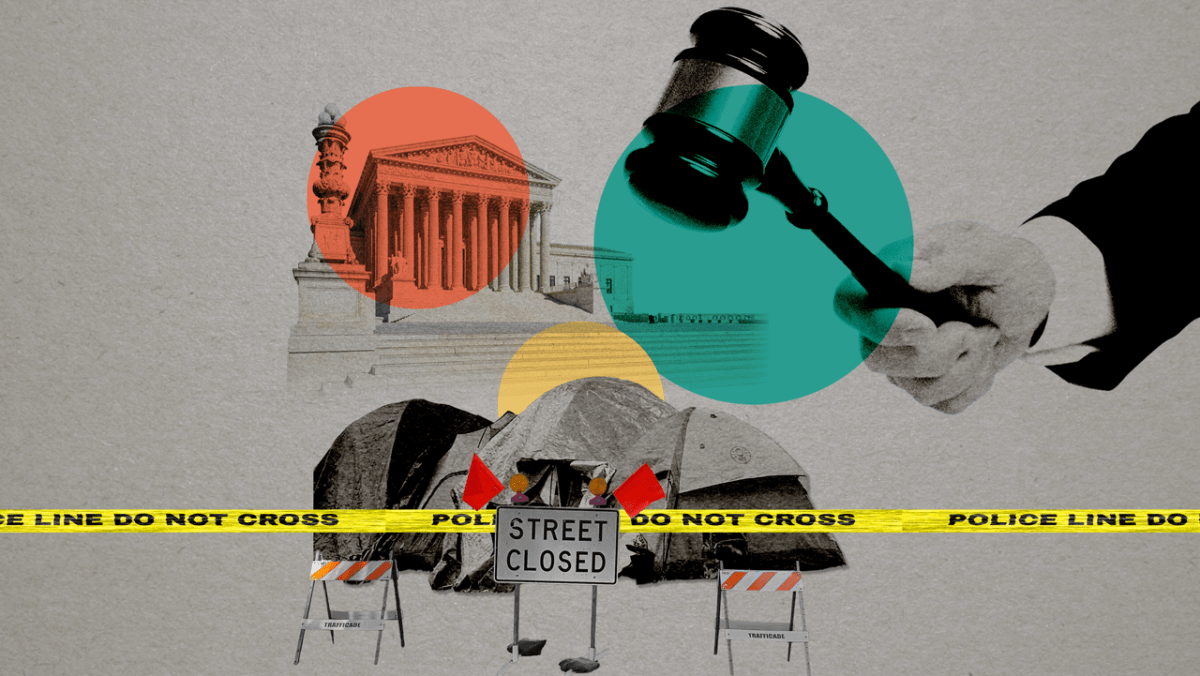

Overview: The Supreme Court ruled that cities can enforce bans on homeless individuals who sleep outside in public places, overturning a California appeals court ruling that found these laws to be cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment. The decision has disappointed housing advocates, who argue that the ruling does nothing to address the root causes of homelessness such as the growing housing crisis, lack of community investments, and lack of consensus on what it means to be homeless. The ruling has led to increased enforcement of penalties such as fines and jail time on homeless individuals, causing a destabilizing cascade of harm.

Breanna Reeves

The Supreme Court ruled that cities are allowed to enforce bans on homeless individuals who sleep outside in public places. The 6-3 ruling, decided on June 28, overturned a California appeals court ruling that found these laws to be cruel and unusual punishment under the Eighth Amendment.

In the case City of Grants Pass v. Johnson, the Court ruled that the Eighth Amendment clause that prohibits “cruel and unusual punishment” does not prevent the City of Grants Pass, OR from enforcing criminal penalties against homeless people who are sleeping outdoors.

“Homelessness is complex. Its causes are many. So may be the public policy responses required to address it,” wrote Justice Neil Gorsuch, who delivered the majority opinion. “The Constitution’s Eighth Amendment serves many important functions, but it does not authorize federal judges to wrest those rights and responsibilities from the American people and in their place dictate this Nation’s homelessness policy.”

With the Court leaving the decision in state hands on whether to enforce penalties such as fines and jail time on homeless individuals sleeping or camping in public spaces, housing advocates are disappointed by the Court’s ruling.

In a state like California — home to 30% of the nation’s homeless population — encampment sweeps are commonplace across cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco. Although homeless individuals are not always criminally penalized, encampment sweeps often inflict more harm on homeless individuals.

“We are literally writing a formula designed to disenfranchise unhoused communities. I will even go as far to say particularly unhoused communities of color, and so it’s painful,” said Claire Jefferson-Glipa, executive director of Family Promise, a Riverside-based organization that serves unhoused children and their families. “This ruling itself is really dangerous work.”

The California Budget & Policy Center reported that in calendar year 2021, among the 270,000 individuals who made contact with local homeless providers, Black Californians comprised over one in four of the unhoused people who made contact.

Jefferson-Glipa emphasized that the Court’s decision is part of a greater theme: “We don’t want to see homelessness.”

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote that criminalizing homelessness and sleep is “unconscionable and unconstitutional.”

“Criminalizing homelessness can cause a destabilizing cascade of harm,” Sotomayor wrote. While acknowledging the dangers and risks of large homeless encampments, she noted the shortcomings cities face with lack of shelters, safety risks among vulnerable homeless individuals, and how unpaid fines among homeless individuals result in the loss of employment and benefits.

According to Jefferson-Glipa, the Court’s decision does nothing to address the root causes of homelessness such as the growing housing crisis, lack of community investments, fractured support services and lack of consensus on what it means to be homeless.

There are two definitions of homelessness often used across the U.S. The Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) defines homelessness across four categories: literally homeless; imminent risk of homelessness; homeless under other federal statutes; and fleeing/attempting to flee domestic violence. However, each category does not receive access to supportive service grants or is subject to partial access to services.

The other definition is utilized by the California Department of Education which uses the McKinney-Vento Act. In this definition, homeless children and youth are defined as individuals who do not have a fixed, regular,and adequate nighttime residence.

Jefferson-Glipa explained that these definitions are lacking in understanding the complexities of homelessness and does not recognize unstable housing such as hopping from one temporary residence to another in order to survive. As a result, homeless individuals and families do not qualify for different subsidies or vouchers under either definition.

Oftentimes, to access resources as a homeless person, organizations examine the length of time spent being houseless (within 30 days), excluding living in a temporary motel or short-term residence. To receive access to some services, a person must be literally houseless, according to Jefferson-Glipa.

“To add fuel to that fire is this most recent decision by those folks that wear those robes — I can’t even call them justices because there’s nothing just about it,” Jefferson-Glipa explained. “We would like for this challenge to not disturb our eyes and to not hold us accountable to the promise of this nation: life, liberty and pursuit of happiness.”

Following the Court’s ruling, Gov. Gavin Newsom applauded the outcome that gives states the authority to “enforce policies to clear unsafe encampments from our streets.”

But local authorities across California have already practiced removing encampments and homeless individuals from public areas, especially in areas in which events are taking place. Some cities have implemented anti-homeless practices such as removing benches from bus stops, adding large planters to sidewalks, and in Los Angeles County, going as far as playing loud music at train stations with large homeless populations to dissuade them from being there.

“It’s a challenge, absolutely, to actually see yourself in the humanity of our unhoused community, and then recognize that we all are suffering the same problem,” said Jefferson-Glipa.