Overview:

New documentary Silver Dollar Road tells the story of massive Black wealth taken through faulty laws and loopholes.

Message from the editor: This article was produced by the nonprofit journalism publication Capital & Main. It is republished with permission.

One generation after the end of slavery, the Reels family bought a plot of land along the coast of North Carolina. They raised their kids along the waterfront and gathered along the banks and at one another’s houses — all along Silver Dollar Road — to celebrate birthdays, parties and holidays. Their property became a safe haven for other Black families looking to enjoy the coast at a time when the state’s beaches were still segregated. Members of the family, including Mamie Reels Ellison and Kim Duhon, still reminisce about those not-too-distant rosy memories today.

As first reported in ProPublica in 2019, the Reels’ family story took a dark turn. One of the descendants, Shedrick Reels, moved away from home and tried to turn a profit by selling land that belonged to the family as “heirs’ property,” land passed down without titles in an era when many African Americans did not trust the U.S. legal system. Shedrick’s decision to sell in the 1970s came to haunt his nephews Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels, who were fighting the new owners for their family’s land, when at a 2011 court appearance, the two brothers were arrested without being charged of a crime or given a jury trial during the eight years they were imprisoned. The pair became the longest-serving inmates for civil contempt in U.S. history at the time of ProPublica’s reporting.

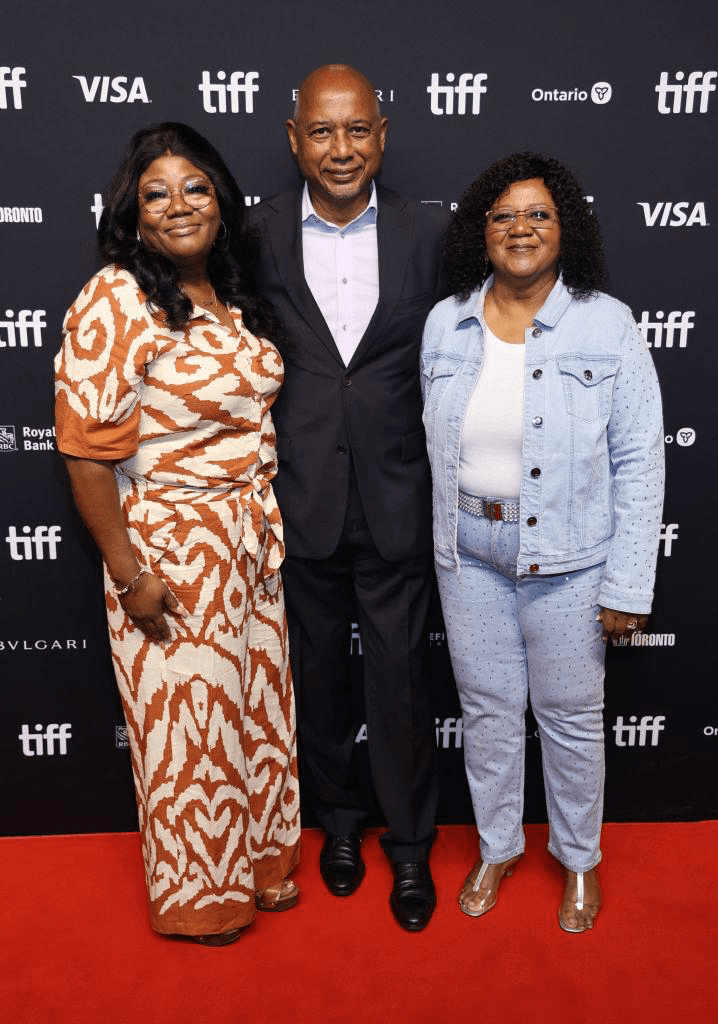

Now, Raoul Peck (I Am Not Your Negro, Exterminate All the Brutes) the Oscar-nominated director who also served as Haiti’s minister of culture, turns his camera on the Reels family’s ongoing struggle to regain their property in Silver Dollar Road.

In collaboration with ProPublica, the director breaks down the Reels’ case and explores the larger issue of heirs’ property and its contribution to the loss of Black family homes. In this conversation with Capital & Main, Peck explains his collaboration process, how Silver Dollar Road is in conversation with his previous documentaries and developing the film with his editor.

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Capital & Main: The original ProPublica piece was published in 2019. What drew you to tell the Reels’ story in a movie?

Raoul Peck: I was offered the project as a producer, and I did my homework. I saw the material. I watched a lot of the archives, the shooting they had done. I read or watched the interviews. I had a pretty detailed idea of what was at stake, the characters, the story, the drama and the extensive research by Lizzie Presser [the ProPublica reporter who wrote the investigative news story]. It had to be a totally autonomous film that you can watch several times, and it’s a film with characters, with storyline, with emotions, with poetry, et cetera.

One aspect is that I could connect the story to my filmography. It almost feels like a trilogy with I Am Not Your Negro and Exterminate All the Brutes because all three speak of land, speak of injustice, speak of America and the role of this country in the history of the world or the history of capitalism. Even though it’s a more personal story about a very specific family, I saw the way to link it to the bigger story and to the biggest structural underlying problems.

Why did you decide to tell the broader story of Black land loss through the family’s personal experiences?

It’s a permanent back-and-forth between the existing material, what you see, what you feel on site, meeting people, having conversations. I had a lot of discussion with Lizzie. She was very often there with us testing different narratives.

At some point, I felt that Lizzie was so deep in that story, I wondered if I could [leave] her out of the narration. But of course, she’s a journalist, and journalists tend not to be part of the story, and I understood that. That helped me see, OK, then I still have to make a choice who is telling the story. I didn’t want to be the one, and very clearly it was Mamie [Reels Ellison] and Kim [Duhon], and at some point it was also a political decision because I had the whole shape of the story, including all the other sides. I could make the artistic choice to say, “You know what? I’m staying with the family.” It’s their point of view. I don’t want to interview whoever is the owner of the property. I want to have my camera inside looking out.

That’s why the images that Mamie filmed were the most important moment in the whole film because it concretized the idea of invaders — the cell phone images with the guy in the back. They are all white, and symbolically, you see the representative of the law, you see the surveyor, you see the guy cutting the electricity. You see it’s the whole society as it is organized that is invading the intimacy of that family. Before that happens, I had to make sure that you felt at home with that family and you were watching the invaders coming in.

This film is mostly built around present-day interviews with the Reels family, which is a departure from your previous documentaries like I Am Not Your Negro and Exterminate All the Brutes. Why did you do it this way?

What decides is always reality. If you have seen my other films or at least some of them, you will see that I use whatever I get and whatever is real. My job is to put it in a way that it means something and people can understand what it means. I had 90 hours of footage, more or less. Not everything was good, but I could make choices because I knew that a big chunk of that would be in the film. I had to see how it looks and because you can’t say, “OK, I’m not going to watch all this. I’m going to start shooting my own thing.” It wouldn’t be rational.

I did the contrary: I edited about 40 minutes of what existed to really see what I have. So, it’s a step-by-step process. People sometimes believe that you just sit down and you have the whole film. No, it’s an organic process. You go one step, and then you see what you have, what is missing, and go for what is missing. And then new ideas come, like the portraits. A film is a process.

When we were ready to shoot, I knew exactly what I wanted to shoot, and I didn’t need to spend six months shooting everything or redoing all the interviews. I knew what interview I needed, I knew what was missing, and I knew who I had to choose to make the interviews. It’s a very different way to approach it, but that’s how I make my films.

Could you tell me more about that collaboration with Lizzie? How closely did you two work together on the film?

She came to one or two of the shooting periods. She came at the beginning because she’s the one introducing us to the family, and then she stepped back a bit because I had to go through my own process. The connection with the family went very well very quickly because they trusted Lizzie. She was really part of the household. She knew everything about them; she knew everybody. When I came, some of them knew about I Am Not Your Negro, so there was a great deal of respect and trust as well. It didn’t take me much time to feel at home as well.

Do you have an update on the Reels and their situation since this film was made?

We all are in constant contact with them. A film is not the end; it’s the beginning of something else. I will be forever linked to them. We are helping as well to make sure that the rest of the property is secure and they are in contact with lawyers who would know how to deal with heirs’ property. There is a wider program in place that we are trying to put in place to link that specific case with all the other [heirs’ property] cases in this country.

There are multiple groups working on that for many years already, but they are spread throughout because each locality has its own set of rules, its own set of laws, which makes things complicated. Some have started reforms, and there is money on the federal level to deal with heirs’ property, but it’s not being used properly. We hope that Congress will renew it in the next farm bill. The idea of the film is that it can attract more attention [to the issue of heirs’ property] because it’s a national problem.

What was your writing process like for Silver Dollar Road since it is different from your previous documentaries?

Well, I would say my most important partner was my editor, Alexandra Strauss, because we really wrote the film together, and there is a kind of osmosis between us, film after film. When you start or when you’re very young, you tend to be in the editing room all the time with your editor because you want to survey every cut, but after so many years of experience and working with the same person, there are incredible shortcuts. If I give her some material, I give her text, and she knows what to do, but usually, I give her storylines, and we bump ideas back and forth, or she can try something. It’s always a work in progress.

It’s complicated, but all films are all complicated in the editing [process]. What do you keep? What do you need for the narration? How do you make sure that the audience will be able to follow a story? Because a story is basically a choice. You choose to tell that specific story, and that’s what I did. I didn’t want to make the story about the back-and-forth of the case. No, it’s a case of a family, told by the family the way they see it, and the drama that it caused. The family will go on, live their life, and the fight continues. That’s the story.

Copyright 2023 Capital & Main