Phyllis Kimber Wilcox |

“She tries to talk to the man about going to the hospital, and how he shouldn’t kill her. She even gets on her knees in front of him and prays to God to spare them both. The man looks up and says “You took everything from me. Just die. I don’t want to hear your voice.”

– Shannon’s Story

Between 2019 and 2020 nearly 30,000 domestic violence related calls streamed into 911 operators from residents in Riverside and San Bernardino Counties.

Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) has been described as sexual, physical, or psychological abuse perpetrated against one partner by another involved in an intimate relationship. These abusive behaviors may include stalking, threatening, hitting, destroying someone else’s personal property, or threatening to do harm to others.

The words domestic abuse or domestic violence often bring to mind what most would think of as traditional instances of abuse or intimate partner violence (IPV). In these cases, the kinds most individuals are familiar with, men are the sole perpetrators of violence against their partners or family members.

These tragedies, while horrific, look like what most dread and expect including—terribly bruised, battered, physically damaged (and in the most severe cases), murdered women and/or children. These horrible outcomes are far too often the experience of people around the world with survivors left to make sense of their experiences while attempting to rebuild their lives.

What Traditional DV Looks Like

Traditional domestic violence cases look like Shannon’s story. Stabbed multiple times by a man who said he would, “always love her.” Shannon survived by packing her stab wounds with sugar and waiting for a time when she felt safe to flee. Although she was offered help, she thought, “[They could] work it out.” Shannon’s background was full of abuse and violence, she had not known anything else her entire life and she feels lucky she lived to tell her story–the price she paid is the scars. She wears the scars of that abuse on her body and in her psyche to this day.

It also looks like Angela’s story. Angela told her story to Amnesty International.

Angela thought she was involved with, “[A] good person.” He was someone she had known for twenty years; however after the death of his mother, her partner’s behavior changed.

He bought a shotgun and a machete and became more combative. After a while, the physical abuse began. Although they broke up, Angela believed it would get better. “[They] were working it out…” That was until the moment he shot her after a disagreement while she sat in the bathtub. The shot left her paralyzed.

Angela survived and now speaks publicly about the issues that changed her life so dramatically including domestic violence and mental health.

While experiences like Angela’s may be the most common, new research is beginning to paint a more complex picture of this serious issue.

A Survivor’s Story

Longtime Inland Empire resident Deborah, (pseudonym) recently opened up to Black Voice News not only about how domestic violence changed her life but also about how, through her healing process, she was able to help change the way victims of domestic violence are treated in the most tragic of circumstances.

Deborah began by explaining how many women are initially surprised by their partners’ abusive behaviors. “It’s pretty typical and I only say this from my own kind of research and going through my experience–it’s not at all atypical.”

Deborah went on to explain how initially an abuser can appear to be charming, to be a nice person, to have their act together. “They seem very interested in you, what you are doing, and how you’re doing it. You know, very supportive—so you enter into the relationship. What you think is a very open relationship. There don’t appear to be any hidden agendas or not any you can foresee immediately. And then, things start to turn.”

Deborah spoke about how initially the warning signs are subtle. In other words, you might recognize them and not acknowledge them. “By that time you’re emotionally invested. You don’t want to see what your eyes are telling you, you’re in some form of mild denial.”

According to Deborah, “When things become more obvious there are three options.” She describes that process as thinking you can fix or cure it, or go into fight or flight or freeze mode. If you fight she explained, “You find yourself defeated physically, if you freeze you try to appease your abuser until they inevitably abuse you again, or you flee and ‘get the hell out of there.’” Though she acknowledged this can often put you in greater danger. “[This] is why a lot of women don’t leave.”

She calls this the cycle of abuse. Deborah tried to fix her relationship, then drifted into appeasement. Finally, when she decided to leave she had to prepare to leave quietly. Deborah was lucky. She had money, a supportive family, and some place to go. These are things a lot of women do not have.

Deborah was able to extricate herself from her dangerous situation with the help of the courts, the police, a support group and her family. Part of her healing process was to go into the prisons and speak with women who were jailed for killing or assaulting their abusers.

At the time, in the late 1980’s early 1990’s, the courts did not allow domestic violence as a mitigating factor when considering sentencing in cases where a victim kills or physically harms their abuser. Deborah was a part of helping to change the law. She’s modest about her role.

“I just jumped on the bandwagon. When I was going through my experience I was very, very fortunate and ended up in a support group with a woman who was very proactive in the area, actually doing counseling and providing legal services to women who were incarcerated. Through her, I was able to dovetail into what they were doing.”

Through the work of these women and others, the laws were changed. It is easier to get restraining orders now and domestic violence can be considered in the instances where a victim harms or kills their abuser.

Sometimes, It is Not Just a One-Way Street

It is often thought domestic abuse and violence is a one-way street, now studies are providing clues this is not always the case. New research indicates some people involved in domestic abuse and/or intimate partner violence (IPV) can be both victims, as well as perpetrators of abuse.

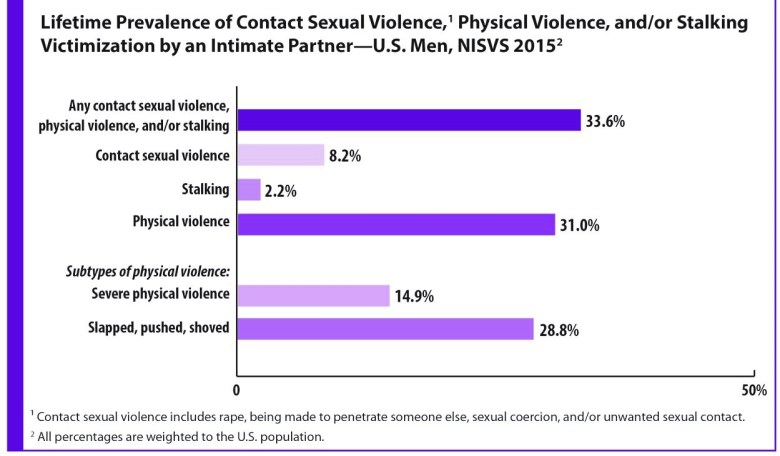

U.S. Men: Lifetime Prevalence of

Contact Sexual Violence, Physical Violence and/or Stalking Vicitimization by an Intimate Partner

The CDC’s National Violence Against Women survey found that 835,000 men are the victims of domestic violence every year. Men who experience IPV tend to under report their abuse. This is partly because they also have special concerns when it comes to contacting authorities. Men especially fear they will be identified as the perpetrator of abuse or fear being punished for defending themselves against an intimate partner who initiates the violence.

Readers may be surprised to learn the National Institute of Justice (NIJ) reports, “In relationships with abuse, a majority of the abuse was reported as mutual, referred to as bidirectional relationship abuse.” The agency further advises, “The rates were also relatively high.”

These findings, NIJ advises, highlights the need to better understand both relationship context and culture aspects undergirding bidirectional IPV in addition to exploring aspects related to prevention and intervention for both men and women.

According to data tracked by Social Solutions, a nonprofit consortium of social workers who use technology to drive social change more than 28 percent of men in the U.S. report having experienced rape, physical violence and/or stalking by an intimate partner in their lifetime. In addition, fully 15 percent of domestic violence victims in California are male. Something to keep in mind in this regard is that male victims of IPV often do not report such incidents because of the “perceived” advantage women have when it comes to using the system to punish or manipulate them.

Domestic Violence is not Just IPV

Domestic abuse is not just violence perpetrated between people who are sexually intimate but may occur between family members such as grown children against elder members of a family, or a dependent adult. This violence is described as elder and dependent adult abuse.

In cases of domestic abuse involving elders or dependent adults, warning signs according to the National Institute on Aging (2020), may include no longer participating in activities they once enjoyed, looking unkempt and dirty, appearing tired or complaining about lack of sleep, and/or withdrawing into themselves. Additional signs of concern may be physical such as unexplained sores, marks, bruises, or cuts. Other signs could include not having access to needed medical equipment such as walkers, canes, glasses etc.

Consider the 2018 case of a sixty-five-year-old woman in the inland region of Southern California when Rancho Cucamonga police answered a call for a welfare check.

When officers arrived at the residence, they found the woman strapped to a chair with a limited ability to speak. They learned she had not been moved in five days. Her caretaker, Brandon Carl, did not see to her needs.

The house was dirty and described as “not suitable,” by police. The woman could not stand on her own. She was taken to the hospital, while her caretaker and his friend, Sebastian Trujillo, who also lived in the home, were arrested.

The tendency to look at domestic abuse as an issue of gender as well as one where there are only singular victims, as well as a singular perpetrator, keeps the focus off providing the kinds of interventions which may be most effective in combating the issues at the heart of domestic abuse.

What are the Warning Signs?

There are warning signs of domestic abuse and usually more than one sign of abusive behavior may present themselves at the same time. In the case of IPV, these signs may not be present at the very beginning of the relationship and may become apparent over time.

This can include hypercritical behavior such as telling a partner or making them feel everything they do is inadequate and/or controlling behaviors such as keeping a partner away from others, especially important people in their lives like family members, friends, or peers.

Controlling behaviors are also common especially around financial issues and controlling physical movement. Jealousy behaviors can also be an indicator of domestic abuse as is pressuring or intimidating a partner into behaviors which normally they would not agree to such as sexual behaviors. The use of drugs or alcohol can also be signs of IPV.

Domestic violence is not just one form of violence, it is not limited by age or gender or sexual orientation or length of relationship. It is the violence perpetrated against those who are closest to the perpetrator. It is violence that can happen to anyone—men and women, children and youth, middle-aged and the elderly. It happens in long-term relationships or in date rape cases.

To stop domestic violence, we have to recognize it when we see it, and do what we can to provide safety, resources and information for those who need it.

Working to End Domestic Violence

The California Partnership to End Domestic violence is a coalition of more than a thousand advocates, organizations and groups across the state. For nearly 49 years the organization has worked in the areas of public policy, communications and capacity-building on cosmetic violence prevention and intervention strategies to advance social change. According to its website, the partnership believes by sharing expertise, advocates and policy-makers can end domestic violence.

Follow this link for Domestic Violence Assistance in Riverside County or this link for assistance in San Bernardino County. In case of emergency dial 911.

The Black Voice News Domestic Violence Series is supported by California Black Media’s Domestic Violence Journalism and Awareness Project and the Blue Cross Blue Shield Foundation of California.

Phyllis Kimber Wilcox is a reporter for Black Voice News. Her interests are the intersections of historic events with contemporary realities and their impacts on the persistent social, structural and economic barriers which continue to adversely affect and limit Black lives with an eye toward community-based solutions.