Last Updated on April 20, 2024 by BVN

Mapping Black California’s Racism as a Public Health Crisis Dashboard is a convenient tool to analyze how governing bodies and nongovernmental organizations have declared racism as a public health crisis and how they plan to address its impact. The dashboard examines the impact of racism on communities of color and analyzes how these declarations will address the systemic impacts.

Breanna Reeves

Editor’s Note: Mapping Black California (MBC), created by Black Voice News, is a project that aims to collect and publish data to help eliminate systemic inequalities. One of MBC’s projects is an interactive map of official declarations by local and regional government officials establishing racism as a public health crisis. The aim of this is to provide a resource for tracking and holding these entities accountable for following through on declarations and statements. For this series, Black Voice News partnered with The Starling Lab for Data Integrity, a research lab anchored at Stanford University’s School of Engineering and the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation. The Lab prototypes authentication technologies and principles to bring journalists, legal experts and archivists into the emerging world of the decentralized web. These tools underscore the importance of accuracy and serve to combat mis- and disinformation. Decentralized tools can create a technological chain that identifies the history, or “provenance,” of a piece of digital content, serving to reduce information uncertainty and bolster trust in digital content. To learn more about these technologies, click here.

In some ways, 2020 can be characterized as the year Earth stood still.

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported 118,000 cases worldwide and on March 11, officially declared a global pandemic as the coronavirus had already swept through 114 countries and killed 4,291 people since January 2020. By March 19, California Gov. Gavin Newsom declared a state of emergency and issued a stay-at-home order.

Time seemed to stop as cities mandated that their residents stay home and shelter-in-place as health officials and the government grappled with a rapidly spreading deadly virus.

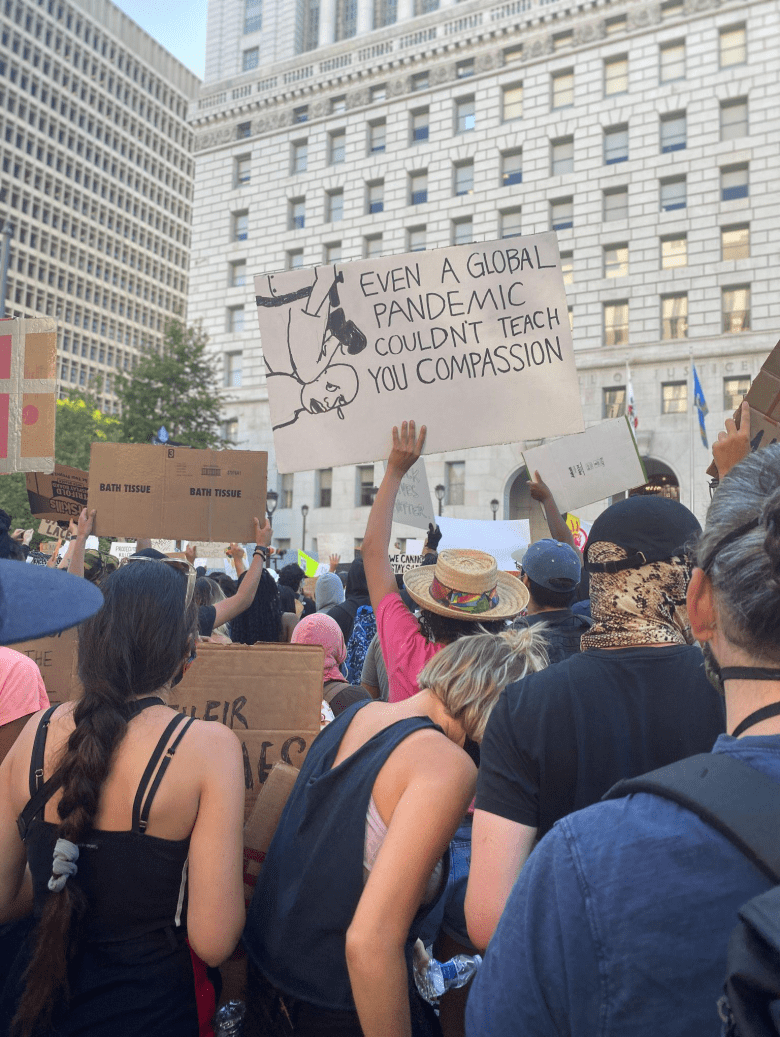

The second time Earth stood still was on May 25, 2020. For exactly 9 minutes and 29 seconds, the world watched as George Floyd, a 46-year-old Black man, was murdered by white Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin. Recorded on camera by Darnella Frazier, 17, the video quickly went viral and reignited a wave of rage among Black communities across the globe.

The murder of Floyd gave rise to a wave of protests across the world as communities, leaders and advocates called for an end to violent and racist practices carried out by police officers against Black people. Floyd’s murder was not the first time a Black person died in police custody or as a result of police actions in 2020. Months before Floyd’s death, 26-year-old Breonna Taylor was killed by Louisville police officers while she was asleep.

Early on in the pandemic, available data showed that Black populations experienced higher rates of COVID-19-related deaths in the U.S. According to an analysis by KFF, when adjusting for age, American Indian/American Native, Black and Hispanic people had higher rates of death compared with white people throughout the pandemic.

The California Department of Public Health began tracking COVID-19 data in January 2020 and found the COVID-19 death rate for Black people was 19% higher than the rate for all Californians.

Factors that contributed to the disproportionate rate of cases and deaths were Black people and people of color made up a large portion of “essential workers” — those who worked throughout the pandemic and who were exposed to the virus without proper safety measures; lack of access to personal protective equipment; and structural racism.

In the midst of it all, thousands of people mobilized on the street to protest sanctioned acts of violence by police, structural inequality that led to the high rates of death due to COVID-19, and demand recognition and reformation of it all.

On June 23, 2020, the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors declared racism as a public health crisis. The first governing body in the state to do so, the board signed a declaration that acknowledged and named racism as the root for many longstanding injustices that impact Black communities economically, socially, mentally, physically and beyond.

“WHEREAS, racism has given rise to geographic segregation that disproportionately exposes people of color to lead poisoning, poor air quality, inadequate nutrition, and under-resourced recreational and healthcare facilities…,” the declaration listed.

At the height of the pandemic, many people associated the declaration with being solely linked to public health, and the disparate outcomes that were made visible.

“But that’s not what it meant,” explained Diana Alexander, San Bernardino County assistant executive officer. “It meant that any kind of racism in a community impacts the health of the public area at large — because of the lack of access, lack of opportunity, the disparagement, the educational impacts, the health impacts, everything. It becomes a public health crisis.”

Following San Bernardino’s actions, the Riverside County Board of Supervisors unanimously voted to also declare racism as a public health crisis on Aug. 4, 2020. As the board recognized racism as a pervasive issue that upholds systems of inequity, they outlined a series of actions that county departments would take to extinguish inequitable practices.

The declaration called for the county to “identify and implement solutions to eliminate systemic inequity in all external services provided by the County including, but not limited to, the following sectors: Health; Social Services; Housing; Homelessness and Workforce….”

Three years after 31 jurisdictions made declarations, signed resolutions and outlined actions, the momentum to address racism as a public health crisis appears to have fizzled with residents not seeing much change to their neighborhoods or circumstances following the summer of protests. In some ways, the declarations seem like a distant memory or even a figment of imagination as focus pivoted to COVID-19 recovery and vaccination campaigns.

Were the declarations made by various governing bodies just words to appease enraged residents? And if not, how are residents able to hold their leaders accountable to their words and actions?

These are questions that led to the development and creation of the Racism as a Public Health Crisis Dashboard by research team Alex Reed and Candice Mays of Mapping Black California (MBC), a Black Voice News project that leverages data to support social justice initiatives. With support from The Starling Lab for Data Integrity at Stanford University and ESRI, Reed and Mays developed the dashboard which assesses governing bodies and nongovernmental organizations that passed resolutions acknowledging and declaring racism as a public health crisis — freezing those moments in time for the public to refer to.

Utilizing Starling Lab’s technology, MBC was able to authenticate the declarations and related documents, securely storing it in digital ledgers, creating a record of origin for digital content (and moments in time) for the public to refer to in the future.

“We’re creating copies of these things [so] that the minute they’re captured — and we use some special tools to capture it, either Browsertrix or Webrecorder — it creates a fingerprint,” explained Lindsay Walker, product lead at The Starling Lab for Data Integrity. “These tools allow you to capture all the code on a website, and mathematically prove what you captured.”

By using web recorder and blockchain technology, The Starling Lab for Data Integrity creates “immutable content” that is impossible to fake or change pieces of content without leaving evidence of those changes.

Blockchain can be described as a digital ledger with hundreds of computer systems recording and validating transactions. Walker described the process as how a bank keeps a record of transactions.

Consider how a bank keeps a ledger of debit card transactions and keeps a record of purchases made. With a bank, there’s a single entity like Chase, who is confirming that a transaction occurred and the account holder and the payee trusts the bank’s record of that transaction. Blockchain works in a similar way, but with thousands of entities (nodes) recording and confirming transactions. These same records can be kept for pieces of digital content like websites and photographs.

“When a major social justice event happens, a lot of promises are made,” Mays stated. “And then once the chatter around it, once the protesting around it, once the media around that event dies down — so do those promises.”

Researchers identified declarations and sorted the contents using the American Public Health Association’s (APHA) analysis template of resolutions as a foundation, and then modified the template to include particular “high needs” of specific regions across the state including COVID-19 and race specific identifiers.

The APHA released an initial dashboard that tracked declarations made across the country, but was more broadly focused on how all communities of color have been impacted by racism. MBC’s dashboard examines the impact of racism on communities of color and analyzes how declarations plan to address the systemic effects.

The rubric for examining resolutions divides them into two categories: Internal Policy & Governing and External Policy & Community Impact. Among the categories are criteria that includes several elements such as data & accountability, funding, community engagement and education. There are a total of nine elements outlined to analyze how declarations measure, such as which resolutions allocated funding or developed community listening sessions to address racism as a public health crisis.

The researchers examined different factors like census tracts and population sizes to determine population densities. Moreno Valley is identified as “Black dense” because Black people account for a great percentage of the total population.

“It’s helping us as researchers target areas that need to have pressure put on them when it comes to making these declarations,” said Reed.

Reed explained that including racial density markers allows other counties to learn from one another in terms of having a greater impact in communities that are Black and minority dense in the wake of the declarations.

At the time of the dashboard’s publication, California led the country in resolutions and there are 10 states that do not have any resolutions, at any level.

Twenty-five of the 31 city and county governments that made declarations included specific strategic actions related to data & accountability including Riverside, San Bernardino, Oakland and Santa Cruz Counties. The dashboard measures this criteria by declarations that stated they would create a task force for the purpose of data collection, issue data reports or conduct data analysis.

“Our North Star is closing racial disparities,” said Darlene Flynn, executive director of the City of Oakland’s Department of Race & Equity. “We have to be able to measure whether or not our services are being equitably distributed, because we know that people of color’s communities have been disinvested for 100 years on the west coast.”

The Oakland Board of Supervisors is one of the few governing bodies that declared racism as a public health crisis later on — in June 2022. With its resolution came actions that called on the city to dedicate financial resources to gather detailed geographic data and allocate up to $350,000 in funding for a Race and Equity Data Analyst and consulting services.

Other resolutions are less detailed regarding how they will carry out the promises made in their declarations, if any were made at all. For some declarations, acknowledgement of systemic racism was the extent of their actions.

At the height of the pandemic and on the frontlines of racial unrest, adopting a Racism as a Public Health Crisis declaration was supposed to be a revolutionary act. Years later, for some governing bodies, the act of doing so appears to have been more of a spectacle than a tangible promise.

Combating Racism as a Public Health Crisis

Part 1: Holding Leaders Accountable

Part 2: Santa Cruz County’s Inclusive Resolution

Part 3: Oakland Addresses Systemic Racism with Data-driven Approach

Part 4: Riverside and San Bernardino Counties Take Action Against Racism as a Public Health Crisis