Last Updated on October 9, 2023 by BVN

Breanna Reeves

It’s clear that legislation as ambitious as AB 1793 required more instruction from the state, more communication between local jurisdictions, a public service campaign and generally, more guidance on the most efficient way to clear records of cannabis convictions.

Vonya Quarles, cofounder of Starting Over, Inc., explained that this has been a consistent issue with laws created at the state level.

“We don’t include in the law, the oversight or the ability to mandate counties to comply or have some repercussions or consequences for not complying,” Quarles said. “These counties pretend to be law and order, and therefore law and order for everyone except themselves.”

John Reitzel, a criminal justice professor at California State University, San Bernardino (CSUSB), said he doesn’t know how courts could have been incentivized to process and clear records in a timely manner because “it’s one branch of the government telling another branch of the government what they have to do in a society [in] which they’re co-equal.”

While AB 1706 eventually, explicitly required the courts to issue orders that recalled, dismissed, sealed or redesignated the cannabis convictions no later than March 1, 2023, one of the flaws in AB 1793’s infrastructure was not establishing a mandate in the first place or including methods of how this work could be done.

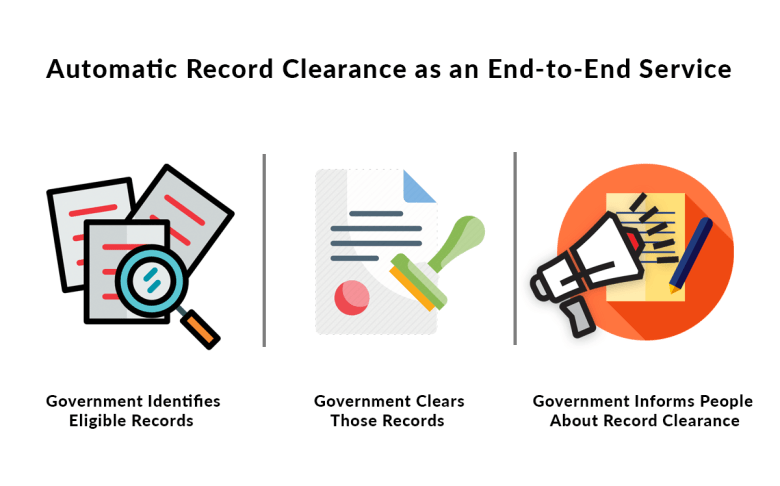

With Code for America’s Clear My Record pilot, the organization realized early on that automatic record clearance is a sizable task that would take substantial work to provide relief to people on such a large scale under AB 1793. Code for America wanted to support all counties in the state with automatic record clearance, especially counties that didn’t have the capacity or know how to streamline the process. To facilitate this they created the Clear My Record application for district attorneys to utilize.

“What we’ve learned and what we’ve recommended for our work across the country for automatic record clearance, is that there’s one central body who is determining eligibility,” said Alia Toran-Burrell, program director of Clear My Record, a service provided by Code for America.

“It’s not based on local jurisdictions identifying records and sending it up to the state. It’s really a state repository or centralized court system that is doing that work instead of individual counties.”

AB 1793 outlined a series of tasks assigned to different entities, beginning with the DOJ who was directed to review records. Assigning each entity specific tasks was intended to “create a state-mandated local program,” according to the law. But local jurisdictions operate differently and with their own set of procedures. It is this lack of consistency that led to the poor execution of AB 1793 across different regions in the state.

Generally, “systems” don’t communicate directly with one another, according to Los Angeles District Attorney George Gascón whose office partnered with Code for America’s Clear My Record. In a way, AB 1793 encouraged entities to communicate with one another in a collaborative manner, from the DOJ to district attorneys to public defenders and the courts to individuals — and like a game of Telephone in which distorted, whispered messages are passed on to other people, each entity had a different understanding of how to approach the law.

Although it has taken four years, nearly all eligible convictions have been granted relief under AB 1793.

According to the DOJ’s quarterly Legislative Report, in July 2019, there were 227,650 past convictions that were potentially eligible for dismissal, sealing or redesignation across all 58 counties. As of April 3, 2023, 206,052 of those convictions were granted some kind of relief. Still, 21,598 potentially eligible convictions remain.

In San Bernardino County, 3,717 past convictions that are potentially eligible for some sort of relief still linger. In Riverside County, just 81 remain.

The promise of automatic record clearance

“California is really at the forefront of automatic record clearance,” Toran-Burrell commented.

Alia Toran-Burrell, program director of Clear My Record, a service provided by Code for America, discusses how California is making progress with automatic record clearance.

With the passage of AB 1793 and subsequently AB 1706, California continues to make strides in implementing automatic clearance policies like AB 1076. Authored by Assemblymember Phil Ting (D-San Francisco) in 2019, the bill requires the DOJ to review statewide records and identify people who are eligible for automatic record clearance and who have already completed their sentence of a diversion program. Under AB 1076, relief is granted to an eligible person, without requiring a petition or motion.

In July, the DOJ released data from the Automated Record Relief (ARR) program as required under the law. The DOJ is required to publish the statistics annually on July 1. The data reflects automatic relief granted from July 1, 2022 to December 31, 2022 and displays statistics on the number of convictions and arrests granted relief across each county.

Approximately six million convictions and arrests have been granted relief under the Automatic Record Relief program across Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego Counties from July 1 to December 31, 2022. (Data visual by Breanna Reeves)

“California laws that prevent people living with a past conviction or arrest record from positively contributing to our communities make us all less safe,” Ting said in a press release.

“After someone has completed their sentence and paid their debts, we cannot continue to allow old legal records to create barriers to opportunity that destabilize families, undermine our economy, and worsen racial injustices.”

Toran-Burnell said California is “leaps and bounds” ahead of many places in terms of being a model for automatic record clearance policy. The progress the state has made toward drug policy reform is notable and a benchmark for other states to follow. As the state moves forward with more reformation laws, the legislature must learn from their successes and failures in order to continue to move the needle to redesign a fair criminal justice system.

Casualties of war

More than 50 years after the war on drugs began, states across the U.S. continue to repair the damage left behind — increase in mass incarceration, growth and abundance of prisons, costs to taxpayers and lives harmed as a result of criminal convictions.

A 2018 report published by the Center for American Progress, an independent policy institute, examined the impact and costs of the war on drugs. The longstanding campaign cost the U.S. an estimated $1 trillion, not considering the monetary costs to incarcerated persons, their families and other social problems.

In California, it costs an average of roughly $106,000 per year to incarcerate a person.

“We’ve had a war on drugs and things like that in our approach to drugs in this country for eons. But the bigger problem is the injustice and the harm that comes from those convictions, and how being convicted back in the 1990s, for instance, might still be harming you in 2022,” Reitzel remarked.

Drug reform policy in the state has improved considerably in the last decade with new laws seeking to restore justice for system-impacted people. California legislation like Prop. 47 (2014) reclassified certain drug offenses from felonies to misdemeanors and Prop. 64 (2016) legalized cannabis, reducing penalties for certain marijuana-related offenses.

With the state’s focus set on lessening the burden carried by past criminal convictions, California is leading the way in automatic record clearance policy.

On July 1, 2023, Senate Bill 731 took effect, which will automatically seal felony records after a certain amount of years. Notably, SB 731 will provide automatic clearance for most felonies from a person’s record four years after the case ends and there are no new felony convictions; prohibit a conviction record for possession of a specific controlled substance that is more than five years old from being used to deny a credential; and automatically seal arrest records for felonies punishable by state prison if no charges are brought within three years.

Introduced by Senator María Elena Durazo (D-Los Angeles), SB 731 marked California as the first state in U.S. history to allow nearly all old convictions on a person’s criminal record to be permanently sealed.

“Eight million people in California are living with an arrest or conviction on their record. Preventing people with a past conviction from positively contributing to their communities is a leading driver of recidivism, destabilizes families, undermines our economy, and makes our communities less safe,” Durazo said in a press release.

Total Drug Arrests by Race

Eight million people in California are living with an arrest or conviction on their record. More than 50 years after the war on drugs began, states across the U.S. continue to repair the damage left behind — increase in mass incarceration, growth and abundance of prisons, costs to taxpayers and lives harmed as a result of criminal convictions. (Data visual by Alex Reed for BVN)

Durazo further emphasized that California spends billions of dollars on rehabilitative services, but if people are obstructed from utilizing those resources, “we are simply wasting that money.”

There is still much work to be done in order to clear the residue left behind from five decades of harsh drug sentencing. Non-profit organizations like Code for America hope to replicate the work they’ve done with Clear My Record in California with other states such as Utah, who has since cleared roughly 350,000 criminal records using Code for America technology.

There’s no exact way to quantify or calculate the irreparable harm done by drug policies over time, but there is no doubt that such laws carried out had a devastating and long lasting impact on Black communities and communities of color, evident by the overrepresentation of Black and Hispanic individuals in prison and in arrest records.

As California, and the nation, work to heal some of the casualties, the hope is that as much focus will be placed on repairing the damage as was placed on creating the problem.

This investigation was supported with funding from the Data-Driven Reporting Project. The Data-Driven Reporting Project is funded by the Google News Initiative in partnership with Northwestern University | Medill

California's Marijuana Reform: Progress Made, But Challenges Persist for Black Communities

Part 1: The Legacy of America’s War on Drugs

Part 2: A Fragmented Criminal Justice System Results in Delay

Part 3: Oversight, Consequences and the Promise of Automatic Clearance