Last Updated on January 12, 2024 by BVN

If you are having thoughts of suicide, you can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 988 or the Inland SoCal Crisis & Suicide Helpline at (951) 686- HELP (4357). Other resources are available here.

Prince James Story

Less than a month after he was placed in a mental health cell for hallucinating and expressing suicidal thoughts, Mario Solis swallowed a pencil, a toothbrush and two plastic bags of soap.

When corrections officers found him — minutes after they had checked on him, according to a Riverside County Coroner’s report — he was lying behind the cell door, toilet water flooded the floor.

Solis, 31, was pronounced dead in the early hours of Sept. 3, 2022, at the Cois M. Byrd Detention Center in Murrieta. The coroner labeled his death an accident.

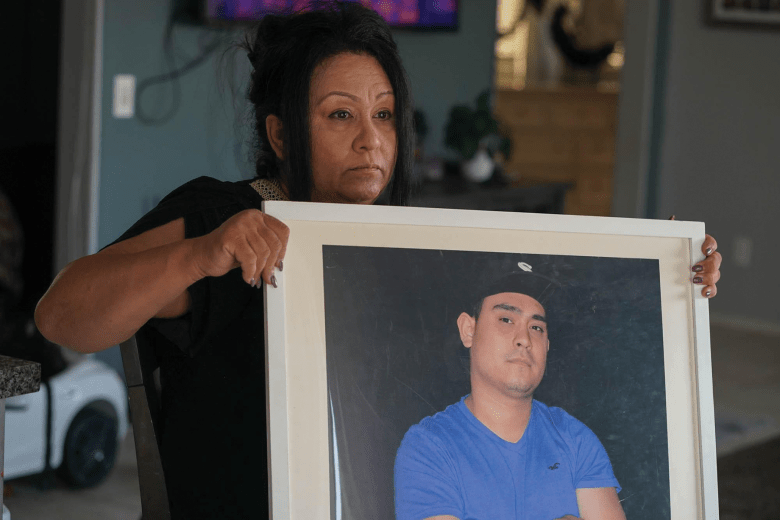

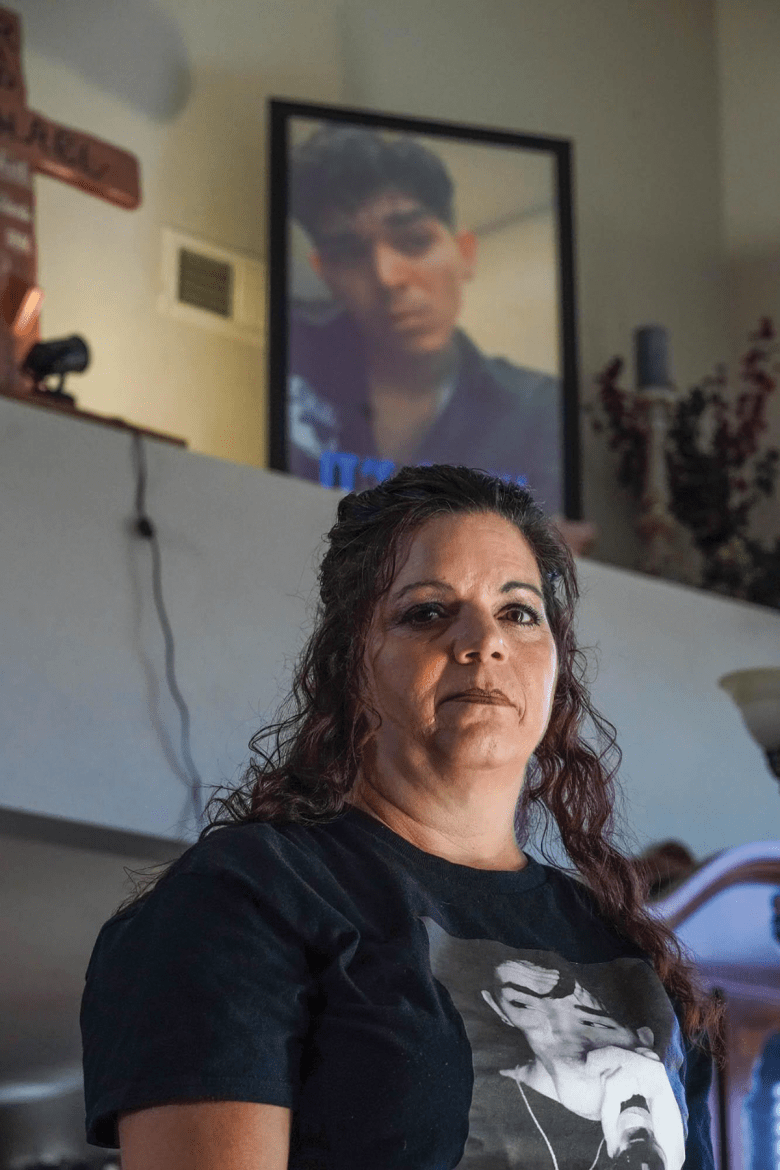

His mother is suing the county for wrongful death and other allegations. Sara Solis claims the jail’s medical staff should have recognized that her son had mental health issues and placed him in a mental health cell when he was booked into jail in April.

Several families of people who died in custody in 2022 are suing the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department for negligence and wrongful death. And the state attorney general is investigating the department for allegedly violating the civil rights of incarcerated people.

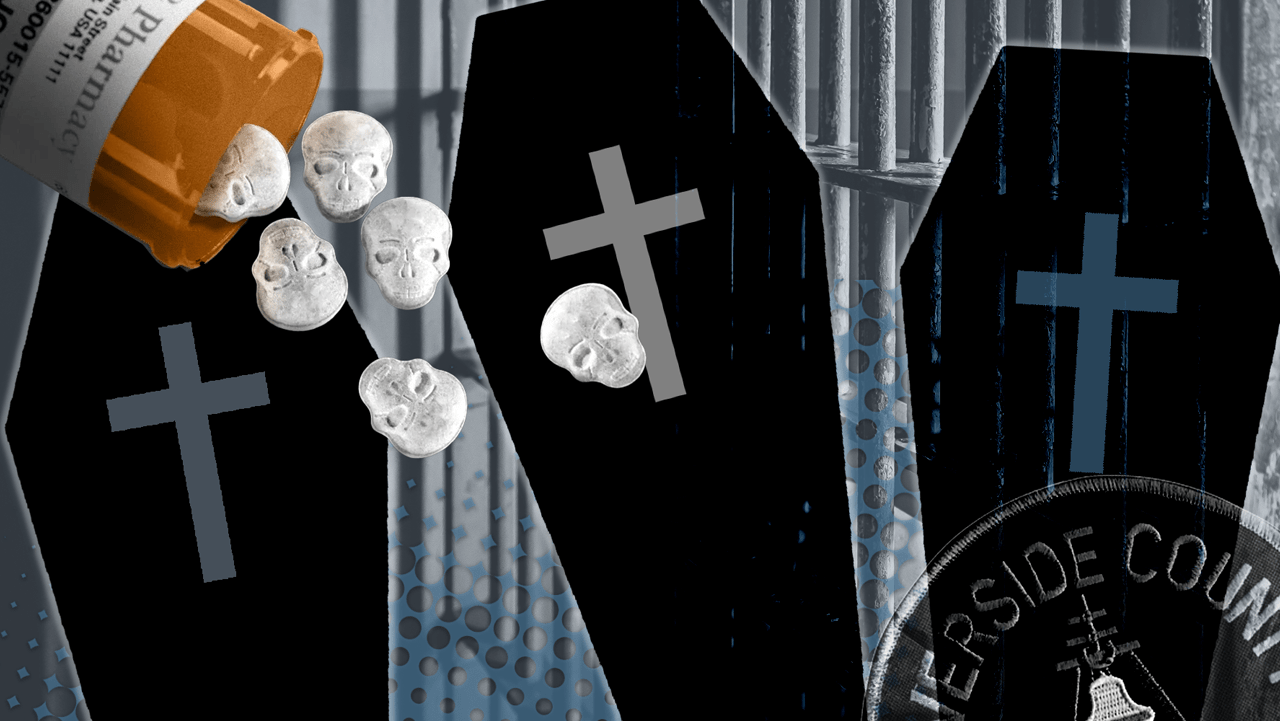

Mario Solis was among 19 people who died in Riverside County jails in 2022 — the third-highest in custody death rate of any large California county, a Black Voice News and inewsource analysis of state jail data found.

(Graphic by Shakeara Mingo, BVN)

The Sheriff’s Department contends that only 18 people died in custody, though it reported 19 deaths to state officials. At issue is whether to count the death of a man in a sobering cell who overdosed and later died in a hospital.

Coroner’s reports, lawsuits and interviews reveal details about the deadliest year in a decade in the county’s jails. Of the 16 coroner’s reports reviewed by Black Voice News, ten of the deaths were listed as accidental overdoses or suicides, five as natural deaths and one as a homicide. The Sheriff’s Department, which oversees the coroner’s office, wouldn’t release two reports and one of the reports is pending authorization for release.

Black Voice News also requested video footage, security logs and other records related to the deaths under the California Public Records Act. After being advised by the Sheriff’s Department on more than one occasion of the need for time extensions to respond, the department finally declared it “has determined that responsive records exist; however, the records requested are exempt from disclosure under the California Public Records Act,” while also directing Black Voice News to Riverside University Health System (RUHS) regarding a couple of items requested.

The people who died in 2022 were primarily Hispanic men, the largest group in Riverside County jails last year. All those who died were awaiting trial and had yet to be found guilty of the crimes that led to their confinement.

The spike in deaths — a jump from 12 in 2021 during the COVID-19 pandemic — happened as Riverside County jails, like many correctional facilities, grappled with a national fentanyl crisis and a burgeoning mental health population.

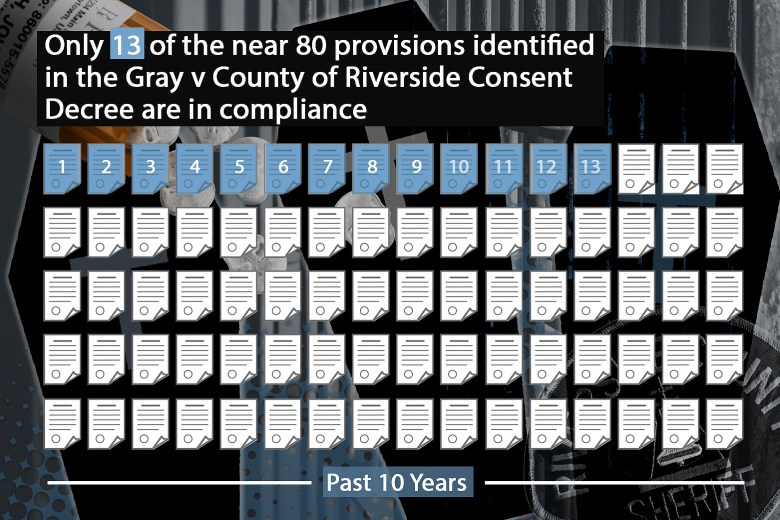

But many of the questions surrounding the 2022 deaths — how corrections officers monitor people in custody and the quality of mental health care behind bars — are similar to issues in a 2013 federal lawsuit that forced Riverside County to improve the medical and mental health care of incarcerated people.

Nearly a decade after a court-monitored settlement in the case, the jails have yet to meet requirements under the ongoing consent decree, an agreement with the plaintiffs in the lawsuit. The county has complied with only 13 of the roughly 80 provisions detailed in the consent decree. The court no longer monitors those 13 items; however, the plaintiffs still dispute whether the jails have satisfied about 67 other provisions in the decree, such as maintaining adequate medical and mental health staff to care for people in custody and effectively evaluating and housing people with the most severe mental health problems.

Sara Norman of the nonprofit Prison Law Office, which brought the lawsuit against the county, said jail officials have improved medical and mental health care for people in custody, but have more to do. Norman, who helps monitor the decree, said the increase in deaths in 2022 is concerning.

“This points to something going on that must be addressed, or maybe multiple things going on that must be addressed,” said Norman, who has asked court-appointed experts to review how the jails investigated the deaths. “The problem lies not so much with medically avoidable deaths as with drug overdoses and suicides.”

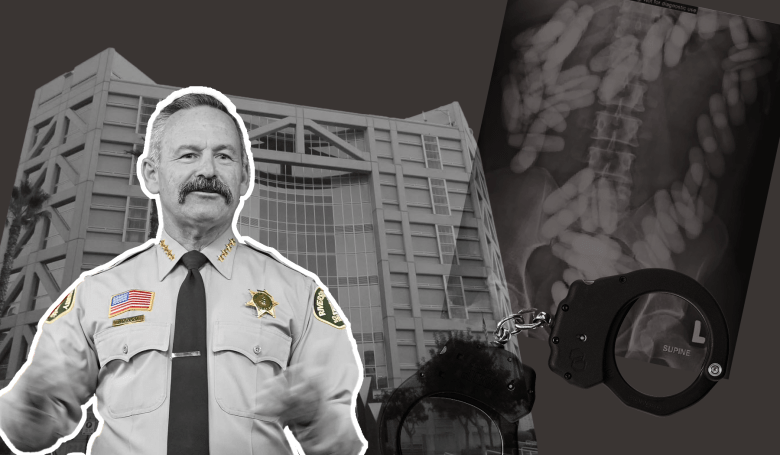

Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco said his staff followed the same procedures in 2022 as in past years when fewer deaths occurred.

“I don’t know why there were that many,” Bianco said of the 2022 deaths, adding that every death concerns him. “It was extremely unfortunate, but it certainly wasn’t at the hands of our deputies. It certainly wasn’t because we weren’t trying to prevent them and stop them.”

Families question jail officials about fatal drug overdoses

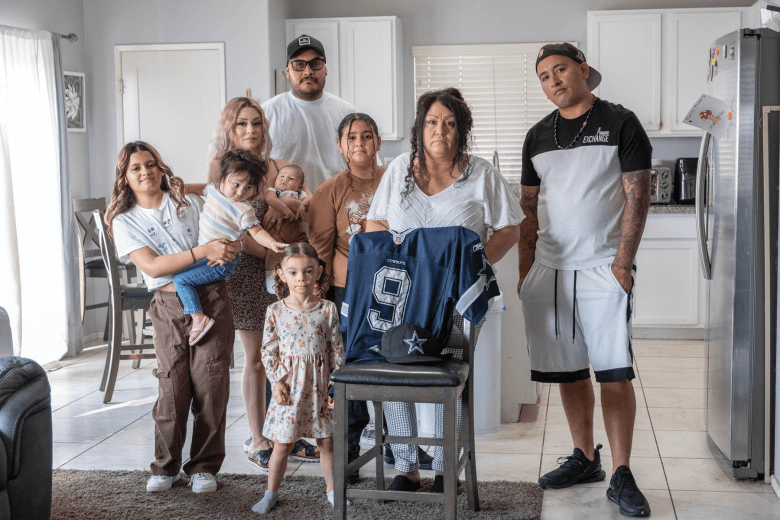

Richard Matus Jr., 29, was one of seven people whose deaths were listed as accidental drug overdoses by the Riverside County Coroner’s Office. He died at Cois M. Byrd Detention Center shortly after midnight on Aug. 11, 2022, his daughter’s first day of eighth grade.

After guards conducted a routine hourly check, records show Matus’ cellmate left the room. When he returned two minutes later, according to the coroner’s report, Matus was unresponsive and lying on the floor. Ten minutes later, his cellmate alerted correctional staff.

At the time of his death, four years into custody, Matus was preparing to represent himself on charges of robbery and attempted murder. He had dismissed his court-appointed attorney, who wanted him to accept a plea deal.

An autopsy concluded that Matus overdosed on fentanyl. But his mother, Lisa Matus, said her son would never knowingly take drugs.

In a wrongful death lawsuit, attorneys for his family claim that deputies didn’t notice he needed emergency treatment because they failed to conduct safety and welfare checks. The lawsuit also cites civil rights violations and medical malpractice, among other allegations.

In an interview with Black Voice News, Lisa Matus also said there were contradictions in the coroner’s report. The initial report didn’t note trauma or abrasions to his body; however, the final coroner’s report stated that there was blunt trauma to his head, abdomen and extremities.

“The autopsy report says there was blunt force trauma but not enough to cause death,” she said. “OK, so then what happened? Did somebody fight him and give him drugs?”

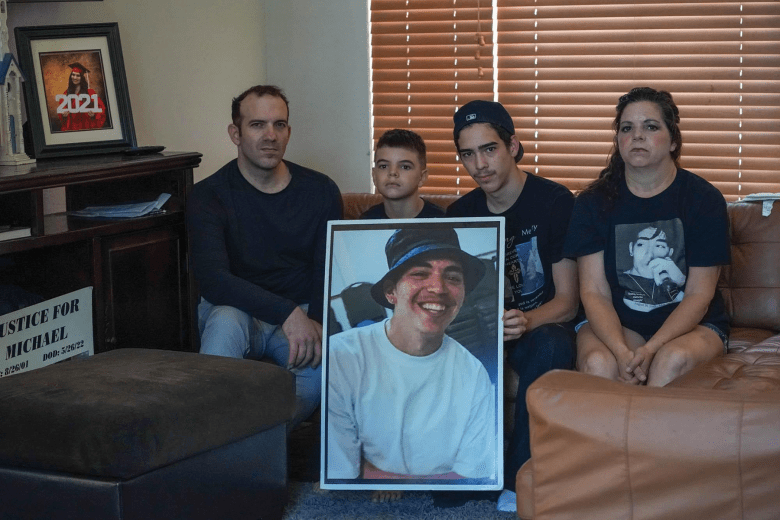

Michael Vasquez also died of a fentanyl overdose in the Cois M. Byrd Detention Center in 2022, according to a coroner’s report. He was one of three people who died of an overdose in the facility and one of two in his housing unit.

Vasquez, who died on May 26, 2022, had been in custody for only six days. At 20, he was the youngest person to die in Riverside County jails last year.

His mother, Kathy Nigro, is suing the county for failing to protect, wrongful death and other allegations. Like Lisa Matus, Nigro believes deputies weren’t conducting hourly inspections of inmates’ cells in general population, as required by state guidelines.

Without security logs or camera footage, Black Voice News couldn’t confirm Nigro’s and Matus’ allegations.

Nigro recalled how she learned her son was dead.

“It was almost 1:30 in the morning, and I heard a knock on my door. It was an officer,” she explained. “He asked, ‘Were you aware your son was arrested last Friday?’ I said yes. He said, ‘I’m sorry. He’s passed away.’”

As the oldest of seven children, Vasquez was considered “the man of the house.” When he was charged with robbery, his mother said she wanted him to sit in jail for a little bit to contemplate his actions. Nigro never thought he would die there.

“I can’t believe he’s not going to come back,” she said.

The fentanyl crisis hits county jails

Nationally, drug overdoses are the third-leading cause of jail deaths. Seven of the 19 deaths in Riverside County jails in 2022 were accidental drug overdoses, according to the coroner’s office.

Fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid, is a particularly deadly threat, Bianco said. Of the 116 fentanyl-related overdoses in 2022, he said jail staff prevented the deaths of 110 people. Black Voice News couldn’t independently confirm the figures.

The jails purchased X-ray machines and hired drug-sniffing dogs to stop drugs from entering the jails, Bianco said, before adding that correctional staff shouldn’t be expected to find everything.

“There is a market to purposely smuggle drugs into jail,” said Bianco, claiming that people get arrested so they can bring drugs into the facilities. “They swallow it, they insert it, they’re underneath their fingernails, their toenails. They do everything they can to try and get it in, and unfortunately, sometimes they make it.”

In late December, the Sheriff’s Department arrested nine people following a two-month investigation into illegal drug smuggling in the Riverside County jails. Five of the people were arrested for conspiring to smuggle drugs into the jails, including incarcerated people, according to the news release.

In an interview in the fall, Black Voice News asked Bianco if he thought correctional staff could be selling drugs in the jails. He said investigators have caught officers doing that twice in the past 20 years. In both cases, he said inmates reported them.

“We know for me to say employees would never bring drugs into the jail — I mean, that’s silly,” the sheriff said.

In September, Bianco dismissed two Riverside County deputies charged with drug possession — Brent Bishop Turnwall, 22, and Jorge Oceguera-Rocha, 25.

Neither was accused of distributing drugs in the jails. But Turnwall was arrested at work at the Cois M. Byrd Detention Center and charged with being under the influence of drugs.

Oceguera-Rocha, who worked at the Larry D. Smith Correctional Facility, was charged with possession of narcotics for sale and transportation with the intent to distribute narcotics. When the department’s Specials Investigation Bureau arrested him, he had more than 100 pounds of packaged fentanyl pills in his vehicle.

Riverside County jails didn’t create the fentanyl crisis. Still, they are responsible for managing it behind bars, said Norman of the Prison Law Office.

The jails have improved how they respond to drug overdoses by equipping deputies with naloxone, which can reverse the effects of opioid overdoses, and doing preventive work, such as talking to people in custody about the dangers of fentanyl, she said.

Norman uses an analogy to explain the county’s obligation to address the fentanyl epidemic. People come into jail with diabetes, which is an epidemic too. The county didn’t cause the diabetes crisis, but it’s responsible for treating inmates who are diabetics, no matter how difficult.

“In a similar way, there is a fentanyl epidemic. It’s terrifying. It’s not of the county’s making, but it’s their duty to address the health of the people in the system,” she said. “And that includes both the security to keep fentanyl out and the mental health [care] to keep people from turning to drugs in despair. “

Improved medical care, but continuing issues with mental health care in jails

When the Prison Law Office sued Riverside County in 2013, the conditions in the jails were “shocking,” said Norman. One plaintiff had been given mood-altering psychotropic drugs, even though he hadn’t been evaluated by a mental health expert.

Another plaintiff suffered severe injuries in an accident shortly before she was incarcerated and didn’t receive timely follow-up care, causing a medical device to become lodged in her body.

Ten years later, the Riverside County jails have significantly improved access to medical care for people in custody, said Norman, adding that the county is “putting a tremendous amount of work” into complying with the remaining 67 provisions in the consent decree.

The agreement, hammered out between county officials and representatives for the jail plaintiffs, requires Riverside County to provide incarcerated people with the same level of care the average person could find in the community. The decree also requires the jails to accommodate people with disabilities.

Among the most contentious issues in the decree are the medical and mental health staffing requirements, which have yet to be achieved. According to the agreement, the jails are required to hire 256 medical and mental health professionals, including doctors, behavioral health therapists and nurses, with different licenses, skills and expertise. To comply with the consent decree, each staff category — for example, psychiatrist or licensed vocational nurse — is required to achieve 90% of its mandated staffing goal.

Although the jails haven’t met the goal, they have improved significantly, Norman said.

The jails have boosted medical staff in all five facilities — once they only had one doctor for all the facilities, now they have multiple people at each jail — and replaced paper health files with a more efficient electronic record-keeping system, she said. “It takes a while to reform a system like this, to build from the ground up,” she explained. “I’m not happy with how long it’s taking, but I don’t find it surprising.”

Janet Zimmerman, a spokesperson for the Riverside University Health System, which provides medical and mental health care in the jails, wouldn’t provide staffing figures for medical professionals, but said there were about 150 behavioral health experts working in the jails.

Zimmerman argues that staff numbers don’t provide a complete picture of the quality of care in the jails. People in custody have access to telehealth options, on-site clinics and specialty care — important elements of quality care, she said.

She emphasized that the jails have met or exceeded standards set by the nonprofit National Commission on Correctional Health Care since 2017, proving that incarcerated people are receiving quality health care. The commission establishes national standards for correctional institutions; however, jails and prisons aren’t required to be accredited by the commission.

Bianco said the staffing goals in the consent decree are arbitrary.

“Ms. Norman knows that we are providing the care that we’re supposed to provide for the inmates. We are not deficient in the care that we’re providing them,” Bianco said. “But she also knows that we’re not meeting the [hiring] requirements. So, she can truthfully say that we are deficient in areas of mental health.”

The number of mental health cases in Riverside County jails has grown more than 50% over the past three years, climbing from 6,600 to 10,300, according to state corrections data.

Aside from staffing issues, the jails aren’t in compliance with other provisions in the consent decree affecting how correctional staff evaluate people with mental health diagnoses.

According to the decree, people housed in safety cells, which are designed for inmates who are a threat to themselves and others, should be evaluated daily by a clinical therapist or someone with more training. Safety cells are padded rooms that have multiple cameras and a door window but no furniture, sinks, standard toilets or objects that people can use to harm themselves or others.

People who are booked and sent to a mental health cell or transferred from the general population to a safety cell should be evaluated by a clinical therapist within 48 hours.

Supervisors are required to inspect safety cells and safety cell logs to ensure that policies are followed and that the cells are cleaned and sanitized. The agreement also requires the jails to develop plans to transition people from safety cells to mental health cells and back to general population cells, if appropriate.

Norman said the new court-ordered mental health expert will present a preliminary report on treatment in the jails in December 2023.

Providing adequate mental health care for people in jails and prisons is a challenge across the country.

Jails and prisons aren’t set up to treat people with mental illness, said Craig Haney, a distinguished professor in the psychology department at the University of California Santa Cruz who studies the effects of incarceration. Yet they’re often forced to provide mental health care without enough staff to safely and effectively manage treatment, he said.

“We don’t have a functioning, adequate public mental health system in the United States,” said Haney. “As a result, people suffering from mental health problems often end up in the criminal justice system.”

Suicides raise concerns about monitoring of incarcerated persons

The day before he died in a mental health cell after swallowing a toothbrush and other objects, Mario Solis refused to take his medication, according to a coroner’s report.

Solis’ death was deemed an accident, though attorneys for the family believe he killed himself.

“Typically on suicides they tell their cellmate or someone would say they were talking about killing themselves or they leave notes,” said Bianco, explaining why the death was labeled an accident. “For him, there was no indication that he was trying to commit suicide. He was just eating things.”

During a mental health evaluation when he was booked into jail, Solis denied having suicidal thoughts. So he was placed in general population, according to a coroner’s report. When he began displaying erratic behavior, the report said, he was evaluated again and placed in a mental health cell for closer observation where he died. (The coroner’s report said he was in a safety cell.)

Denisse Gastélum, who is suing the county on behalf of the families of Solis and Alicia Upton, who also committed suicide in 2022, said the jails aren’t properly monitoring people with mental illness.

When a person is booked into jail, they’re screened to determine if they have mental health issues and to decide where to house them. The consent decree requires a registered nurse to ask them a series of questions, including whether they have attempted suicide in the past or are thinking about it. If they answer yes to any of the questions, they’re referred to medical and mental health staff for further screening.

Safety cells, the most restrictive housing, are reserved for people at risk of hurting themselves and others. State guidelines require deputies to check on people in safety cells every 15 minutes.

People with other “severe” mental health diagnoses are placed in mental health cells with cameras so they can be monitored. People with less critical diagnoses are placed in general population cells without cameras, where deputies check on them hourly as with all incarcerated people, said Riverside County Chief Deputy James Krachmer.

Upton, 21, was in a mental health cell at the Robert Presley Detention Center when she tied her bedsheet to the top bunk and hanged herself on April 28, 2022. According to a coroner’s report, deputies didn’t notice Upton’s body on camera or start life-saving measures for 20 minutes.

Footage from a camera in the cell showed Upton looping the bed sheet around her neck, the coroner’s report states. Four minutes later, she tied the sheet to the upper bunk and hanged herself

When she was booked into jail on April 19, Upton told jail officials she “always kinda [sic] wanted to die” and said she had multiple personalities, the report said. Two days after being booked, she was put in a safety cell after kicking other inmates’ cell doors; later, she was moved back to the mental health cell, where she hanged herself.

“It’s very clear that their mental health staff doesn’t know what the hell they’re doing in those jails,” Gastélum said. “Because Ms. Upton and Mr. Solis committed suicide in such tragic and obvious ways, they missed every single sign that you had a suicidal [incarerated person] on your watch.”

Gastélum doesn’t represent the family of Robert Robinson, who killed himself on Sept. 7, 2022. Still, his death also raises concerns about how well deputies monitor people and the quality of mental health care in the county jails.

Robinson, 41, died less than 24 hours after arriving at the Robert Presley Detention Center, where he was in protective custody in a single cell, according to the coroner’s report. On the day of his death, he warned jail personnel that he would kill himself. But after consulting with a mental health professional, he was returned to his cell in general population housing.

A video shows him hanging himself right after an hourly cell check, according to the coroner’s report. Deputies didn’t discover his body until more than an hour later. A toxicology report detected amphetamines and morphine in Robinson’s system.

Referring to the suicides, Bianco said there’s a limit to what jail personnel can do.

“We do everything in our power to prevent suicides. The bottom line is if someone’s going to kill themselves, they’re going to find a way to kill themselves,” he said. “And usually, it’s not the first time they try. They keep trying until they’re successful.”

Questions about accountability

But before the spike in jail deaths in 2022, the Sheriff’s Department had been under scrutiny for years for its treatment of people in custody and officer-involved shootings.

“These things have been happening in Riverside for a long time. The only difference is that the numbers have spiked to a ridiculous level,” said Luis Nolasco, senior community engagement and policy advocate at the ACLU of Southern California, which urged Attorney General Rob Bonta to investigate the Sheriff’s Department.

Since 2014, several Riverside County grand juries have investigated the department, recommending a range of changes, some of which are relevant to issues surrounding the 2022 deaths. The department rejected most of the recommendations, according to grand jury records.

A grand jury suggested that medical or psychiatric staff conduct routine rounds in holding and sobering cells to ensure people are receiving timely mental health support.

On Aug. 26, 2022, Octavio Zarzueta Jr., 30, died at a local hospital after being held in a sobering cell for public intoxication. His family is suing the county alleging corrections officers failed to properly assess or monitor him.

Another grand jury recommended that the department improve how it maintains incident logs, providing a more accurate, detailed description of what happened and identifying who wrote the report. The jury also proposed that the reports be screened for continuity and reviewed by a supervisor. Families suing the county have challenged the accuracy of jail records.

Lisa Matus and other family members of people who died in custody in 2022 are waiting for answers from Bianco.

“All we want you to say is, ‘Let me look into it. Let me see what happened.’ Because obviously, [the sheriff] wasn’t there,” she said. “So how can he say he knows that everything’s good across the board if he’s not in all the jails all the time watching what people do.”

Gail Fry contributed to this report.

This project is a collaboration between the Investigative Editing Corps and Report for America and produced with support from inewsource, a nonprofit investigative newsroom in San Diego.