Last Updated on December 4, 2023 by BVN

Luca Martinez

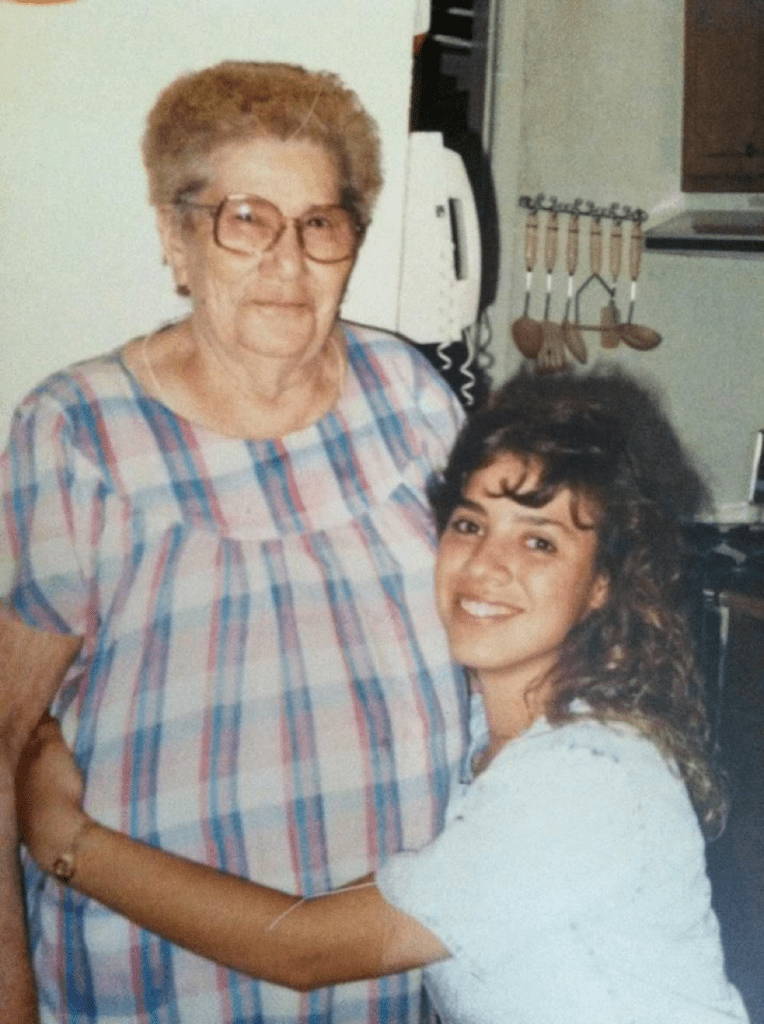

As a child, Yvette Marquez-Sharpnack would begrudgingly help her mother Vangie and grandmother Jesuista in the kitchen. Cooking Mexican food was a significant element of her Mexican family and their El Paso, Texas home.

But unlike her two elders, Marquez-Sharpnack didn’t feel a connection to the food in her younger years. Back then, she remembers the family teasing her for a lack of cooking desire.

“They said I would never find a husband without knowing how to cook,” said Marquez-Sharpnack, while laughing.

It wasn’t until years later that Marquez-Sharpnack realized the importance of keeping her family’s food and culture alive.

Marquez-Sharpnack recalled a specific day in her mid-20s when she craved her grandmother’s red enchiladas. Now living alone and away from her family, she called her mother to ask for the specific recipe.

That soon became a routine habit.

“I missed my culture, and I realized it was all surrounded by the food, parties and the celebrations,” Marquez-Sharpnack said. “Everything revolved around food.”

Eleven years ago, at the suggestion of her 8-year old daughter, Marquez-Sharpnack began preserving these recipes to share with the world. She eventually co-wrote a cookbook with her mother to showcase their family’s generations of authentic Mexican food.

“No matter what color you are, what your ethnicity is, food is our love language,” Marquez-Sharpnack said. “My food is not only for Mexican people or people who are of Mexican descent. That’s what I am trying to share. That anyone can make these recipes.”

Those feelings of love and togetherness toward food are not unique to Marquez-Sharpnack. Food is an universal human experience, with all people eating to live. But food is more than just a means for survival. It is also how people connect, retain and share their culture.

Food and Identity

There’s no doubt that food and identity are connected,” said Dr. Anthony Jerry, an

assistant professor of anthropology at UC Riverside. “People build their identities around food.”

In America, one of the most ethnically diverse and multicultural nations in the world, individuals will often try foods from different cultural and ethnic backgrounds. And lately, research shows that is happening more frequently.

According to the National Restaurant Association, 80% of consumers eat at least one ethnic cuisine per month and nearly one-third tried a new ethnic cuisine in the last year. The 2015 survey also found that two-thirds of consumers say they’re eating a wider variety of ethnic cuisines now than they were just five years ago.

A 2018 study showed people are willing to pay more for ethnic foods.

“Americans generally are more willing to try new food than they were only a decade or so ago, especially in restaurants, underscoring that the typical consumer today is becoming more adventurous and sophisticated when it comes to different cuisines and flavors,” said Annika Stensson, director of research communications for the National Restaurant Association, in a statement.

But this increase in ethnic food consumption and appeal comes at a time when hate crimes are on the rise across the nation.

The bias-fueled violence surged nearly 12% between 2020 and 2021, according to statistics released by the F.B.I. last March. The majority of the hate crimes reported, 64%, were prompted by prejudice based on the victim’s race or ethnicity.

A question about cultural connections

The disconnect between consumption and hate crimes raises questions about how effectively food is facilitating barrier breaking and bridging cultural connections.

“There’s a distance sometimes between people and their habits around consumption, and the people that represent, or the cultures that those foods represent, that might limit the possibility of bringing people together,” said Professor Jerry.

For Professor Jerry, there is no doubt that food allows for the opportunity to bring people together. But it takes more than just eating the food of a different culture.

Making cultural connections

So, how does a person get to the point where they create a relationship with the culture and people instead of just consuming the ethnic food?

The first step may be to understand the history of the term “ethnic” food and its controversial roots.

Dr. Krishnendu Ray, a professor of food studies at New York University, studied the influence of different food cultures in his 2016 book The Ethnic Restaurateur.

The term “ethnic” first appeared in the United States during the late 1950s, Professor Ray said.

At that time, the Civil Rights movement was quite visible and it led to the creation of “ethnic” — a third term in the relationship between Black and white.

“Ethnic becomes this not white, not Black, not foreign, but cheap and spicy,” said Professor Ray.

He argues the ethnic food category becomes associated with the food of poor immigrants in the United States and is seen as the opposite of fancy foods. In his book, Professor Ray cites the price of gourmet restaurants as evidence. Cuisines viewed as lower or stemming from poor people are routinely priced lower.

Mexican food is an example of this logic, historically associated with poor people’s food. Though the group has been the largest wave of immigrants in the U.S. since 1965, they have generally not escaped this perception.

“There’s still a lingering idea that if it’s authentic Mexican food, it cannot be expensive Mexican food,” Professor Ray said.

“Dipping their toes” into the culture

Studies reveal Mexican food reigns supreme alongside Chinese as the most popular ethnic food. But only about 2% of Mexican restaurants in large American cities are up-scale restaurants, Professor Ray said. In some ways, popularization can work against a food raising in the hierarchy of food.

That might explain why the sole increased consumption of certain foods doesn’t lead to breaking down barriers of discrimination and negative stereotypes.

“As humans, we’re really slick at compartmentalizing,” Professor Jerry said. “The food is one thing but the people—that’s different.

Professor Jerry gave an example from a few years back, when he was listening to NPR. In an audio clip, he heard a white woman expressing her love for Mexican food, but also blaming Mexican immigrants for her husband not being able to find a job.

“She really enjoyed the fact that Mexican folks, through food, enriched her life and the way they provided something for her to consume,” he said. “But when that relationship was turned upside down, it felt to her like they were taking from her.”

Food, Professor Jerry said, is a way for people to “dip their toes” into the culture but not fully commit. To go further, there must be environments where the food can be shared among people from different cultures and boundaries can be crossed.

Only then can people learn about the similarities of backgrounds, leading to the creation of relationships. Professor Jerry cited potlucks, block parties and intimate settings with the chef of the food as examples of how these relationships can be formed.

“Food is a starting point,” he said. “It brings people together. But does the rest of the environment facilitate the sharing process? If it does, the food is going to help do that work.”

Community restaurants in the Inland Empire, through their own family histories, are creating environments to build that community and break down barriers. We’ll examine those eateries and people to better understand how they form cultural connections.

For those restaurants, and Marquez-Sharpnack, food is that first step.

“With what’s going on in our world, I think there just needs to be more love and more inclusivity,” said Marquez-Sharpnack.

“We all have a mother, a grandmother and a lot of those special memories that we have with our family are about the foods that remind us of them.”

This project was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library.

Food is the Language of Love

Part 1: Everything Resolves Around Food

Part 2: A Restaurant Unlike Any Other

Part 3: The Taste of “Little Thumb”

Part 4: Spreading Nicaraguan Culture through a Dream Come True