Last Updated on June 24, 2024 by BVN

Overview: Ron Clayton, a Fontana native, became homeless after losing his wife and two adult children, leading to severe anxiety and depression. His health conditions worsened while living on the streets, and he was unable to access medical care due to clerical red tape. The link between health and homelessness is often overlooked, with poor health being a major cause of homelessness and homelessness exacerbating health conditions. The homeless population is aging, and the state’s healthcare system is difficult to navigate, especially for older adults. The state’s Master Plan for Aging aims to address the needs of the growing older adult population, but the lack of current information on the costs and results of homelessness programs makes it difficult to determine if their programs are successful.

Aryana Noroozi

In 1999, Fontana native Ron Clayton, 67, tragically lost his wife Debi to an asthma attack and what he believed was a broken heart. After losing two of their adult children, she gave up, he said.

After losing his son in a tragic accident and a few years later, his daughter while he was incarcerated, Ron sunk into a deep depression. He eventually developed intense anxiety that severely hindered his ability to function, including working, paying bills and maintaining his emotional and mental well-being.

“It is a loss. It’s one thing to lose a child — f— that, but [when] your wife is just gone, what do you do? I lost it,” Ron said.

From a young age, Ron had goals about where he would work, and how he would retire early and become a grandfather. He previously worked in a Sunkist plant in Ontario and later, as an Automotive Service Excellence certified mechanic. Ron opened his own mechanic business in San Bernardino. He enjoyed traveling, woodworking and was proud that he paid off his home. He never expected to lose his wife and child back-to-back.

“You do the dope to hide the emotions and then the dope takes over,” Ron said. He described how each morning he woke up feeling lost and the desire to drink, do a line of drugs, smoke a pipe — anything to take away his grief.

Ron is bipolar, schizophrenic and suffers from major anxiety disorder. He was diagnosed approximately 20 years ago. Shortly after his wife’s death, he sold his truck and RV for a fraction of what they were worth and “went off the grid.” He had no contact with anyone and lived in a secluded outdoor area in Redlands.

His journey to becoming homeless was ignited by loss, resulting in Ron experiencing a serious decline in his physical, mental and emotional health. While homeless, Ron also served time in prison.

Ron’s story is one of many that point to a vicious cycle between health and homelessness. Mental and physical health conditions can lead to one losing their home and landing on the streets which then creates and compounds health problems and makes it harder to access care. Poor mental and physical health conditions can lead to an individual losing their home and landing on the streets, which creates and compounds further health complications. This presents obstacles to accessing care, creating a cycle of homelessness in which health is a key factor keeping people on the streets.

Fractured systems lead to gaps in access to care

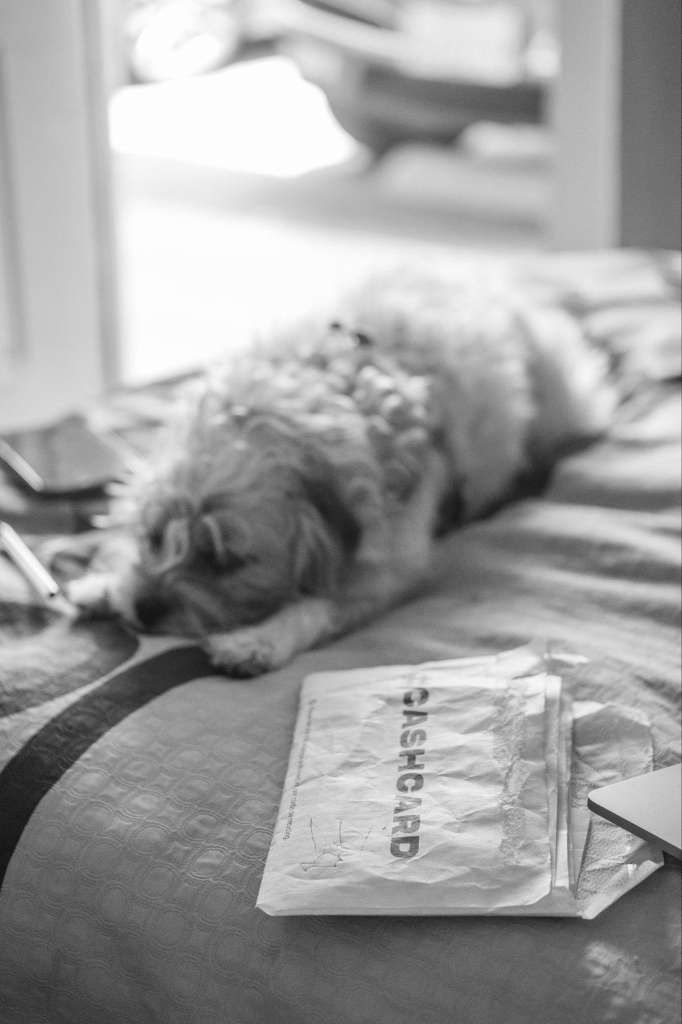

Ron was recently placed in housing in a San Bernardino motel, after living on the streets for more than 15 years. Kristen Malaby, Healthcare in Action’s Care Management Supervisor of the Inland Empire region, was able to connect Ron to services through the Salvation Army after someone attempted to harm him while living in an encampment. The charity organization is currently partnered with San Bernardino County to provide housing in the motel through the Housing and Disability Advocacy Program.

Having a secure place of his own to sleep every night has improved some of his health conditions, but not others which include chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (CPOD), injured joints, heart problems and dental needs.

However, the greatest challenge for Ron remains the state’s inability to process his paperwork that indicates he is no longer in prison. Ron was released from prison in 2019, yet is still unable to access medical care due to clerical red tape. Effective in January 2023, under CalAIM’s Justice-Involved Initiative, people who meet criteria, such as having a confirmed or suspected mental health diagnosis, and are preparing to be released from prison are eligible to be enrolled in Medi-Cal 90 days prior to their release.

Ron was recently turned away from a dental office where he hoped to receive dentures. The office receptionist explained that the incarceration hold on his records indicate that he is still in prison, and therefore unable to receive treatment.

Currently, Ron receives treatment from Healthcare in Action, an organization of healthcare professionals, community health workers and social workers who provide medical care to unhoused individuals across California by traveling directly to homeless encampments. They try to provide as much medical care as possible under limited conditions and funding. Ron receives services and medication for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, anxiety and depression at no cost until he can resolve the complications with Medi-Cal.

Shouldering the burden of being homeless together

Ron recently met Missy, 44, who began living on the streets less than a month ago. They met when their dogs ran up to one another at the hotel. Their stories bear similarities.

Missy became homeless after a close friend relapsed on methamphetamine and kicked her out of his home. She had been his caretaker while he received treatment for cancer.

“I dropped everything to help other people, and this is what happens,” she said. “This is why people give up on people and I’m trying not to do that.”

Like Ron, Missy also lost her youngest son, Shiloh, who was only a child when he passed away due to health complications.

Missy also has a history with substance addiction.

“When you sober up, your feelings come back and they come back hard and you have nothing to crutch,” she said. “You have nightmares. You wake up and you can’t smoke something to make you go back to sleep. You can’t smoke something while you’re sitting there awake with all those images still in your head.”

Missy makes sure that Ron takes care of his health. She reminds him to take his medications and helps him apply nicotine patches, among other tasks.

Ron and Missy are among 4,195 people in San Bernardino County experiencing homelessness, according to the 2023 San Bernardino County Homeless Point in Time Count survey.

With $24 billion spent by state and local governments to address homelessness in the last five years, resources are often focused on solutions such as housing, rehabilitation and harm reduction.

For those like Ron, whose health conditions can lead to homelessness, there is a significant need for mental health care for aging adults at an earlier stage in their life.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI), social determinants of health are factors in a person’s life, such as the conditions in the places where they live, learn, work and play, that increase their health risks and impact outcomes, including mental health.

NAMI points to the link between a person’s ability to access housing and how this can affect mental health and wellness, and the ability to maintain housing or a job.

“Once homeless, if individuals have poor health, their poor health can reduce their energy and ability to complete tasks that would be needed to resolve their homelessness such as gaining employment, finding housing, and attending appointments with service providers,” said Marcus Cannon, the deputy director of behavioral health at Riverside University Health System. He explained that while homeless, chronic pain can also worsen and lead to substance use and abuse.

Homeless older adults face worse health risks

A 2022 UCSF study that followed and surveyed 450 older adults for four and a half years in Oakland, CA, found that individuals who became homeless at age 50 or later were roughly 60% more likely to die while living on the streets than those who became homeless earlier in life. Although the study was limited in size, it gives a glimpse into the outcomes homeless older adults face.

“My health sucks. I can’t breathe. I have bad shoulders, knees and hips,” said Ron. While homeless, Ron has been struck by moving vehicles three times while riding his bike. He suffered a stroke in 2002, and a heart attack last October.

Cannon emphasized how stable housing is vital for long-term health improvement and maintenance.

“Stable housing provides the predictability and stability needed to build a foundation of health,” he said. “Without stable housing it is difficult to store or refrigerate medications, hygiene can be compromised, chronic stress increases and sleep is catastrophically interrupted. All of these have profound negative impacts on health.”

“I’ve always had to try to hold this [together],” Ron said, pointing to his head. “Losing my wife and children made it harder and harder.”

As Ron’s mental health deteriorated and he found himself on the streets, his physical conditions also worsened. He would carry supplies out to the secluded encampment where he lived. Ron recalled carrying 12 gallons of water and falling, further injuring his joints.

Coupled with Ron’s age as an elderly adult experiencing homelessness, he is at higher risk of worse outcomes. According to the state’s Homeless Data Integration System (HDIS), of the 148,000 older adults (50 years and older) who were served by homeless programs, 40% experienced chronic homelessness between July 1, 2018 and June 30, 2021.

Chronic health conditions such as high blood pressure, diabetes and asthma can become exacerbated by living on the streets as it is difficult to store medication, prevent it from being stolen or destroyed, as well as receive refills from the pharmacy and consistently take it.

In addition to chronic conditions, mental health conditions require consistent medication and the repercussions of not taking them can be severe and even fatal.

Twelve percent of the state’s homeless population reported experiencing hallucinations in a 30-day time period and more than a quarter said they’d been hospitalized for a mental health condition, according to a recent UCSF survey.

Street medicine health care providers locally and across the state have found success by meeting patients where they are — in encampments or outdoor public spaces. However, as California’s homeless population grows, the need for more expansive and equitable care still lingers. For older adults like Ron with increasing physical health needs, street medicine won’t suffice.

Additional barriers to accessing health care and navigating the state’s healthcare system include the lack of digital literacy among older adults who are used to speaking with people over the phone. Now, many systems are digital and allow beneficiaries to access important documents online or through a phone app, but older adults fail to navigate these apps and often forget their passwords, Malaby explained.

“[They] have to now deal with and try to navigate the world in the form that is now nearly impossible,” she said. “In fact, it shuts a person down.”

State plans for addressing homelessness still fall short

With nearly a third of the nation’s homeless population residing within California, seniors are estimated to be the fastest-growing group. From 2017 to 2021, California’s overall senior population grew by 7% while the number of people 55 and over who sought homelessness services increased by 84%, an increase greater than in any other age group.

As Ron’s experience indicates, homeless seniors face additional obstacles to receiving healthcare in a system that is difficult for individuals of all ages and circumstances to navigate.

“If the system would have been here I would not be in this position right now,” Ron said. “The system has failed and everyone knows this, but no one gives a shit.”

When examining solutions from the state, California’s Master Plan for Aging outlines strategies for the next decade, in effort to address California’s growing older adult (60 and older) population and their needs. By 2030, 10.8 million Californians will be an older adult, accounting for one-quarter of the state’s population. The first goal to accomplish by 2030 is housing for all ages and stages.

According to the California Department of Aging, to address the growing crisis of older adult homelessness, the California Department of Aging (CDA), with support from philanthropic partners, convened multi-sector leaders and subject matter experts to focus on strategies to prevent and end older adult homelessness.

“The solution to preventing and ending older adult homelessness requires a whole-of-society approach involving government, community organizations, philanthropy, and private partners,” said Garth Stapley, Information Officer at the California Department of Aging.

In April a statewide audit was conducted on the billions spent related to homelessness across California. The results of the audit reported that the state doesn’t have current information on the ongoing costs and results of its homelessness programs because the California Interagency Council on Homelessness has not analyzed spending past 2021. Much of the major funding sources failed to produce the adequate data to determine whether or not their programs were successful.

“State level data is always appreciated, but we don’t need state level data to confirm decades of research that show that lack of housing worsens health,” Cannon said. “Conversely, we have decades of experience of housing homeless individuals, keeping them housed and seeing their health improve.”

Since securing housing, Ron’s health has improved, however, he cannot receive the total care he needs until his issue with Medi-Cal is resolved.

“Homeless people need close help, not [services that] come by once a year, but help continuously,” he said.

Unlike Ron, Missy’s time on the streets just began. When she became homeless she called to find services for herself and her dogs. Her dogs received temporary housing and were taken away while Missy remained without services.

“I didn’t receive anything. I didn’t receive any other phone calls back,” she said. “How far does it have to go before I actually do receive help? Do I have to go all the way to being down in the dirt? Do I get a tent?”

For now, Missy is focused on supporting Ron as she waits to access services.

In spite of his current situation and ongoing health needs, Ron is receiving some health services that are helping to support his physical and mental health needs. Eventually, like thousands of adults in the state, Ron will require more care as he continues to age.

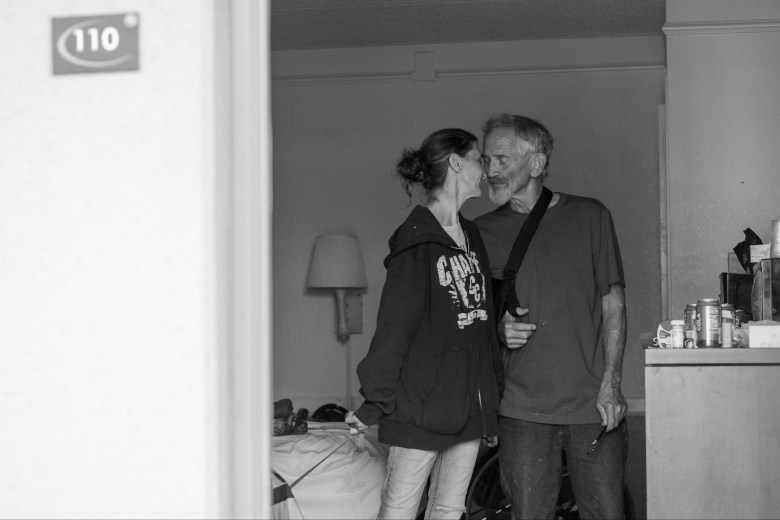

Recently, the Healthcare in Action team paid Ron a visit in his motel room, and met Missy for the first time. They all shared that they had not seen Ron this happy in a while and were pleased to find someone was helping him keep up with his health. Some of the team members chatted with Missy about Ron’s medications.

After they left, Missy remarked how well Ron did with five different people from the street medicine team in the small motel room. Ron and Missy shared a smile and talked about Ron receiving shoulder surgery once his insurance clears and how Missy will care for him.

“If you make somebody smile and they’re happy, then that person will make somebody else smile and they’ll be happy,” said Ron. “The world should be happy and not so greedy.”

This Black Voice News project is supported by the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism, and is part of “Healing California,” a yearlong reporting Ethnic Media Collaborative venture with print, online and broadcast outlets across California.