Last Updated on March 8, 2023 by BVN

Image: Chuck Bibbs

Breanna Reeves |

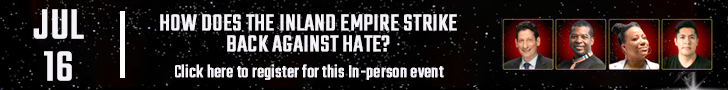

Reentering your community and rebuilding life after paying one’s debt to society is often riddled with unexpected obstacles and impeded by limited access to support. In this series, you will follow the reentry journey of Michael Jurado, a formerly incarcerated individual, as he navigates the challenges faced by himself and others as they struggle to cleanse themselves of the stigma of incarceration and discover the community organizations working valiantly to fill gaps in support left open by state and local governments.

Michael Jurado remembers being released from state prison in Corcoran, California, in October 2017. It was a Thursday and 31 years after he’d resigned to spend the rest of his life in prison.

A Los Angeles native, Jurado cycled through the criminal court system from age 17. He spent a year in a juvenile detention camp after being accused of brandishing a firearm in Inglewood. At age 21, he was arrested for his involvement in a robbery that resulted in the death of two people and another being seriously injured. The charges carried the death penalty, but Jurado was ultimately sentenced to 57 years to life under a plea agreement.

Jurado expected to spend the days following his release with his family in L.A. before he started a mandatory transitional program in San Diego. But, he was only able to spend one night at home. His parole officer told him he was going to start his program immediately.

Successful reintegration into society can be difficult to measure, but there are some factors that are considered important to researchers in reducing the chance that a formerly incarcerated person will reoffend. A 2011 Justice Quarterly article explained that social ties to family and stable employment are two key factors that play a role in the reentry process.

Dr. Annika Anderson is a sociology professor at California State University, San Bernardino. She also leads the CSU San Bernardino chapter of Project Rebound, a program that supports formerly incarcerated individuals pursuing their degree. In her research, she examines how community characteristics like high poverty and crime rates, access to services and family acceptance can impact reintegration.

“We have to remember that people who have committed crimes are also family members. They’re spouses, they’re parents, and they can positively contribute to society, especially if they’re given a second chance,” said Anderson.

Through it all, Jurado said his family was always supportive. He served four years of his sentence at Pelican Bay State Prison in Northern California, a 730-mile trip one-way from Los Angeles.

Jurado said that his family – especially his mother – was his “main support system” while he was in prison. “They made that 18-hour trip up there to visit me. That resonated with me because it didn’t matter where I went, they were always supportive,” he said.

A new law and Jurado’s “controlling offense”

Jurado never expected to be released from prison, let alone an early release. He was prepared to live out the rest of his life in prison for a crime he committed as a young man. Serving the minimum sentencing term, he would have been nearly 80 years-old if he was ever released.

But, a new state law passed in 2017 required the Board of Parole Hearings to consider parole for any offender’s “controlling offense” committed before they turned 25. A “controlling offense” is the charge a person was sentenced to that carries the longest amount of time incarcerated. (Effectively, this law eliminated life without parole terms for juvenile offenders because these offenders became eligible for parole in their 25th year of incarceration.) Jurado was granted early parole at his first hearing, a very rare decision by the parole board.

“I know God’s hand was in my freedom, and now it’s [about] what I’m going to do with this blessing. So, going into a reentry program was always a part of that transition. My thing is, most lifers are mandated to go to a program. [But,] what about people that don’t have life sentences?” Jurado asked.

most lifers are mandated to go to a program. [But,] what about people that don’t have life sentences?” Jurado asked.

Process failures in access to state’s rehabilitative programs

Access to programs in prison is determined by assessments that examine a person’s risk to reoffend, their behavioral needs and educational needs. State facilities offer in-prison programs in efforts by CDCR to increase rehabilitative services that reduce the odds newly released people will reoffend or be re-arrested, what’s known as recidivism.

However, a study of in-prison rehabilitative programs by the California State Auditor found that CDCR failed to consistently place incarcerated people on waitlists for rehabilitation programs and didn’t correctly prioritize those with the highest levels of need. The Auditor concluded that 62% of imprisoned persons who were released in fiscal year 2017-18 were released without having their rehabilitative needs met, despite being identified as having a high risk of reoffending post-release.

Rehabilitative services offered in CDCR facilities include Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to treat substance abuse and rebuild family relationships, vocational education training programs and academic classes. Despite these offerings, some people leave prison without having ever received or participated in any programming. And, they’re released with no guarantee of rehabilitative programming to help them re-enter society.

Newly released people in California often leave prison with just two hundred dollars — if they’re lucky. It’s not uncommon for a newly released individual to have no housing, employment or even transportation in place upon release. Jurado explained that from the time a person leaves prison with about $200 loaded onto a debit card they’re issued, they’re constantly chipping away at the only money they have to pay for necessities needed to leave the prison grounds.

Activation fee: $3. Bus ticket home: $87. First meal post-release: $20.

“So by the time you get home, you might have like $96 or something, and that’s what you’re supposed to base your future on — $96. You don’t have any clothes but what you brought with you from prison,” Jurado said.

“It’s like a setup for failure and [there’s] nothing in place that can assist these people getting out of prison in succeeding.”

Jurado believes that anyone released from prison should be afforded the opportunity to enter a transitional program, regardless of sentencing or time spent in prison. Anderson, however, suggests a different approach: risk needs assessment. The sociologist explains that it’s important to assess the needs of individuals on a case-by-case basis and examine their circumstances in order to address their immediate needs.

“We really need to think about how there’s not a one size fits all approach to everyone’s reentry process, especially in terms of the programs that we recommend individuals take,” Anderson said.

Anderson’s model relies on examining risks to specifically target people for “intensive services” based on their personal risk levels. “Who’s at a higher risk for recidivism compared to others?” she said. Anderson’s model hinges on thinking about what people need holistically, as a whole person with specific needs, in order to reduce their chances of reoffending.

A new approach to reentry

Transitional housing programs are geared toward helping vulnerable populations who may be experiencing housing and job insecurity. These programs offer structure and stability for individuals who need support and encouragement amid uncertainty. Such programs can play a vital role in the successful reentry of people newly released from prison.

Measuring the success of reentry is subjective and relative to specific components of a program, but some studies have demonstrated that community-based programs have positive outcomes. A 2019 analysis of successful approaches to reentry by the Harvard University Institute of Politics explains that community-based organizations emphasize other factors that lead to successful reentry because their priorities often differ from those of government-based organizations:

“Many of the criticisms of government-based organizations center on the fact that most of these programs focus on work and employability alone. Although these programs are successful to the extent that beneficiaries are able to secure jobs, these programs often fail to target the intersection of issues present at unemployment for formerly incarcerated citizens, nor do they focus on success in that particular job. On an even larger scale, these government-based programs tend to fail the communities they set out to help because they are rooted in states that consistently invest financial capital into incarcerating people while never focusing on the root of the crimes that plague the neighborhoods they often target.

“These issues often fall into the sphere of community-based programs, which emphasize larger issues of access to social services like healthcare, housing, and economic development.”

The analysis referenced the success of a community-based reentry program in Colorado called Work and Gain Education and Employment Skills (WAAGES) that reported a 2.5% recidivism rate for program members.

Additionally, a report published by the Justice Policy Institute last year compiled recommendations for improving reentry based on an analysis of Washington D.C. reentry service providers and stakeholders. Increasing representation of employees with lived experience in prison who can help others returning home.

Vonya Quarles launched Starting Over, Inc. in 2009 to work with individuals “who are returning, or who are carrying the collateral consequences of a criminal conviction.”

Quarles is an attorney, executive director of Starting Over and a founding member of the Riverside chapter of All of Us or None (AOUON), a grassroots organization that advocates for the rights of formerly and currently incarcerated people and their families. She also has firsthand experience with the prison system as a formerly incarcerated individual herself.

Quarles explains that it’s easy to write people off who have past criminal or felony convictions that can impact their reentry and reintegration process. But Starting Over and other community-based organizations seek to stop that way of thinking by reminding the community that formerly incarcerated persons deserve the same opportunities afforded to everyone else.

A new start

Starting Over blends direct services with civic engagement. The organization offers supportive services, including transitional housing with sober living and harm reduction, peer support, employment and financial and legal literacy services. Starting Over teaches those seeking services to be advocates for themselves and people like them.

A holistic approach from community-based programs like Starting Over can lead to better outcomes.

Since opening in 2009, Starting Over has helped hundreds of women, men and children who have been impacted by the criminal justice system in some way.

According to Quarles, Starting Over provides transitional housing to approximately 150 people per year while serving and working with an additional 400 people across other programs offered, such as the post conviction relief clinic, participatory defense hub, case management and advocacy programs like the Family Reunification Equity, and Empowerment (FREE) project.

Research published by Dr. Anderson, Noe J. Nava and Patricia Cortez in 2015 found that essential human needs’ resources like housing and food assistance, and legal assistance were two of the most frequently requested services among newly released individuals in San Bernardino County.

Starting Over has supported more than 7,000 people since opening, despite being a small organization that Quarles describes as underfunded.

Jurado chose to complete a transitional program in San Diego because he wanted to give himself a better chance at success, which meant leaving behind his old neighborhood and acquaintances. During the program, Jurado had stable housing, daily access to counselors, group counseling sessions, support, and transportation when he needed to complete important tasks like getting his driver’s license.

Recognizing the barriers to successful reentry created by problems with the state’s corrections system, Jurado began working with the San Diego chapter AOUON, which led him to Starting Over.

Jurado met Quarles when he relocated to Riverside, where his family lived after he completed his transitional program in San Diego. Then, Quarles was the director of the Riverside chapter of AOUON.

When Jurado and Quarles met, she asked him where he saw himself fitting into Starting Over. “She said, ‘Well, you make your position,’” Jurado recalled. So, he started as a volunteer with the organization.

Starting Over partners with other organizations such as AOUON to address and campaign against discriminatory policies that impact incarcerated and formerly incarcerated people. For instance, the Family Reunification, Equity and Empowerment (FREE) Project supports families who are navigating Child Protective Services and advocates for family reunification.

Partnerships have been critical in distinguishing Starting Over from other service-providing organizations because it combines direct services with policy and advocacy. Starting Over implements a “strength-based approach” to work with individuals — supporting and valuing the work they do and encouraging their self-advocacy.

Missteps moving forward

The prison system, arduous to navigate and difficult to leave behind, penalized Jurado again a few years after his release. He violated a condition of his parole when he visited his girlfriend’s son in prison.

Violating parole conditions — “technical violations” — can result in reincarceration, a factor that contributes to the steady recidivism rate in California. According to The Washington Post, 58.8% of California’s parolees went back to prison for a technical violation in fiscal year 2018-19.

California defines recidivism as “when a person is convicted of a subsequent crime within three years of being released from custody.” A California State Auditor report found recidivism rates for inmates in California have averaged nearly 50% over the last decade.

“I was inclined to go visit [my girlfriend’s son] and try to inspire him and just encourage him. I was rearrested as an ex-felon on prison grounds,” Jurado explained. “Vonya represented me in that criminal case. She got the case dismissed, but being a life inmate, I had to go in front of the [parole] board.”

The board found Jurado suitable for release after completing a 14-month sentence. He joined Quarles at Starting Over as a participatory defense coordinator. Jurado’s job is to help families that have loved ones with open criminal cases create social biographies to help humanize their loved ones in front of the court and foster community support for the accused.

“In terms of my job assignment, I also assist with food distribution where we give out food every second and fourth Friday of every month. I do outreach, too. I don’t keep myself in a narrow lane. I try to assist wherever I’m needed,” said Jurado.

The need for sustainable funding

While community-based programs have proven to have some impact on reentry success, sometimes more than government-led programs, these programs struggle to receive funding at the same level.

When Starting Over initially began, funding was scarce on the heels of the 2008 financial crisis. Quarles and her team did what they could to provide direct services.

“What we came to understand was that it was very, very difficult for Black-led organizations to get funding,” Quarles said. “So much so that funders began to recognize the disparity of who was getting funding, who had access to resources and capital, and who didn’t.”

It wasn’t until 2020, during racial protests in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder coupled with the COVID-19 pandemic, that Starting Over experienced an influx of resources they’d never had or expected. The organization learned to look beyond the local sector for funding and began extending their search for funding to the state and federal levels.

However, the limited amount of funding allocated to community-based organizations is a symptom of a flawed system in which local programs aren’t prioritized nor are the communities they serve.

“We get about 45% of our budget from foundations and 45% from adult reentry [state] grants,” Quarles explained. “And 10% from private donors, board members, board fundraisers, etcetera.”

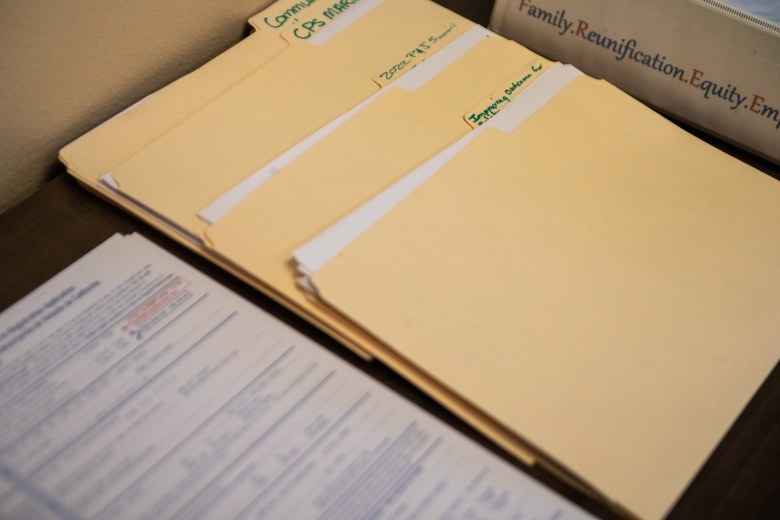

Starting Over, ACLU of Southern California and AOUON submitted a joint complaint last July, citing misuse of funds from the federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The funds were designated for programs specifically addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, but the complaint alleges millions of dollars given to Riverside County went to the Riverside Sheriff’s Department.

According to the complaint, the department used the funds for non-pandemic purposes: $2.7 million for office renovations, $1.3 million to upgrade its key card/video camera system and $660,000 to bulletproof its windows.

Funding for such programs has proven to be complex especially when dealing with pandemic-related issues such as health care for persons being released from state and local facilities. The organizations are still awaiting a decision regarding the recovery of the CARES Act funds.

With several dedicated donor partners and annual fundraiser luncheons, Starting Over manages to encourage, support and provide services for a community of people that society tends to write off.

“What’s amazing to me is that we’ll keep doing something that we know isn’t working over and over and over again. And that’s the way I see the criminal justice system — we know it’s not effective,” Quarles said, explaining that she will continue to ask why the same structure is in place if it doesn’t work and offer up more effective alternatives.