Last Updated on March 8, 2023 by BVN

Image: Chuck Bibbs

Breanna Reeves |

Reentering your community and rebuilding life after paying one’s debt to society is often riddled with unexpected obstacles and impeded by limited access to support. In this series, you will follow the reentry journey of Michael Jurado, a formerly incarcerated individual, as he navigates the challenges faced by himself and others as they struggle to cleanse themselves of the stigma of incarceration and discover the community organizations working valiantly to fill gaps in support left open by state and local governments.

In 2015, Santa Clara public defender Sajid Khan was assigned to represent 14-year-old Christian Haro Cotero. Cortero was being prosecuted as an adult by the Santa Clara district attorney’s office after he confessed to the non-fatal stabbing of 17-year-old Manuel Esquibel.

Cotero’s mother contacted Silicon Valley De-Bug, a community advocacy organization based in San Jose, for help. De-Bug reached out to Khan to meet Cortero’s family.

“Through the course of that case, I worked with Christian’s mother and with the people from Silicon Valley De-Bug to develop information that would be helpful to Christian’s defense and to try to secure the best outcome for him,” Khan explained.

Behind Cotero’s crime was a history of abuse at the hands of his father and subsequent depression, a history that Khan laid out to prosecutors when he urged them to keep the case in juvenile court — which they refused. Detailing Cotero’s mental, emotional and familial history to the court as a mitigating factor in his case is one of the methods employed by De-Bug.

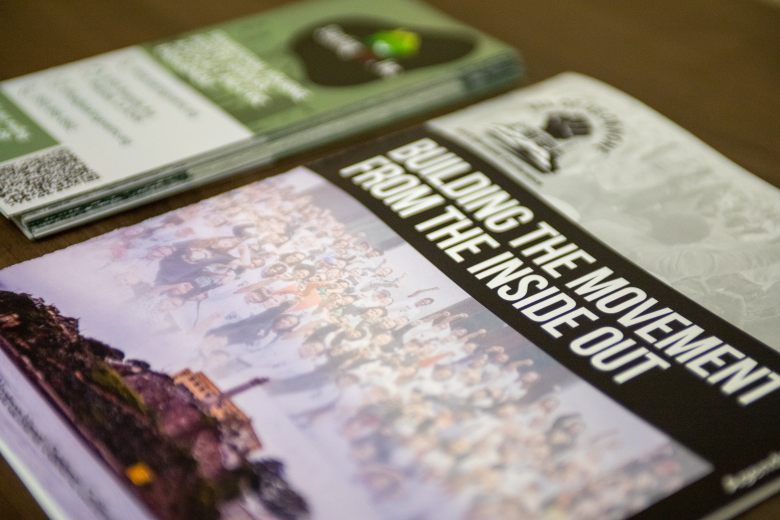

Participatory Defense

This approach is called participatory defense, a community-based process developed by De-Bug to support people facing criminal charges. Participatory defense involves creating “social biography packets.” In simple terms, it’s a dossier that presents the person facing charges to the court as more than a case number, more than another offender.

“Defense attorneys call this a mitigation packet, and they’ll hand this to the district attorney and say, ‘Here are all the reasons why you shouldn’t give this person four years for…say [breaking] into a store,’” explained Zach Kirk, who works for De-Bug. Social biography packets are intended to provide context, to present extenuating circumstances such as a history of mental and emotional problems, physical abuse, substance abuse or other tough circumstances that contributed to criminal behavior.

In his role, Kirk supports organizations who practice participatory defense, whether it’s assisting with training, filling out data requests or walking an attorney through training.

Cotero’s case was the first time Khan had used participatory defense in court as a public defender. Khan said he was initially hesitant to communicate with and involve community organizations and families in the direct representation of people because he was trained to maintain clients’ confidentiality.

“I came up as an attorney where we are trained to keep our cards pretty close to the vest and where we don’t really let ‘outsiders’ into our process,” Khan said. “So, it was hard to imagine how we could incorporate people outside of that fold into the representation. [But,] I’ve learned that there’s a significant benefit to our clients that can be gained from this model.”

Social biography packets consist of personal background information, pictures and other details about a person’s life and circumstances. They can include letters from drug counselors or doctors about mental health as well as statements from rehabilitation programs.

The packets show the court that the sum of a person’s experiences should be considered when a person is sentenced for a bad decision they made. The goal is to get a lesser sentence than what’s being offered by the district attorney or is recommended by the penal code, whether that’s no incarceration or less time incarcerated.

Growing a network

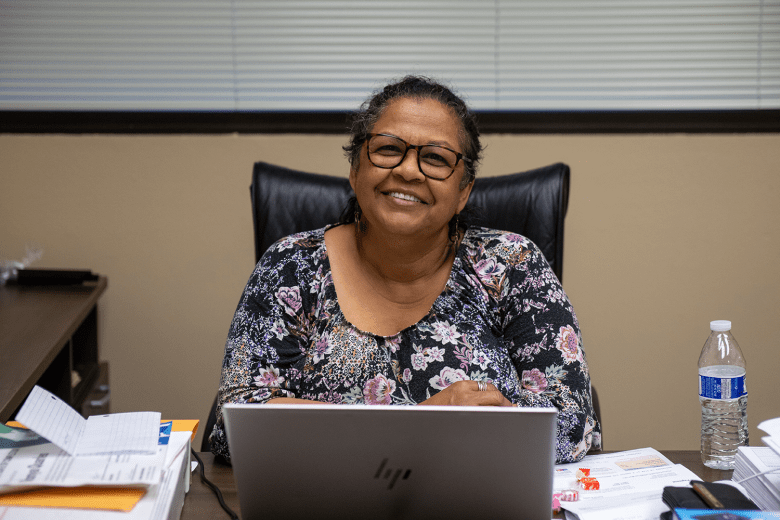

Vonya Quarles is co-founder of Starting Over, a nonprofit organization that provides support and services to people who have been impacted by the criminal justice system. She was first introduced to the participatory defense model in 2016 during a discussion with Raj Jayadev, De-Bug’s founder.

“It was exciting to me as a criminal defense attorney to actually feel like you could lean into the community to help bridge the differences that we see when it comes to resources, and criminal prosecution,” Quarles said.

The participatory defense model was developed in 2015 by Jayadev, who is also the coordinator of Silicon Valley De-Bug’s Albert Cobarrubias Justice Project. Before participatory defense and its focus on humanizing defendants, families and community members crowded courtrooms in a show of support and to pressure judges in sentencing. There was no “singular approach” that helped families, Kirk explained. There was a lack of organization and an inability to communicate with attorneys regarding the law and how to best support their family members like there is now.

Participatory defense has grown into a national network with several dozen hubs across the U.S. De-Bug affiliates that use the model, host training and informational meetings and introduce the model to public defenders and other attorneys. The hubs don’t offer legal advice. Instead, they work to train and educate family members on how the court operates and how their loved ones could be impacted by sentencing.

Starting Over is part of the Inland Empire’s participatory defense hub. Michael Jurado is a participatory defense specialist with Starting Over. His job is to assist people who have loved ones with open court cases. Along with his colleague, participatory defense organizer Toya Vick, Jurado meets weekly with families to help them navigate the court system and create social biography packets.

Vick was trained as a participatory defense organizer in 2017 while she was facing life in prison after being falsely accused of fraud. While facing charges, Vick put together a portfolio of her life that detailed her accomplishments and gave it to her attorney. At the time she was a commissioner for the city of Moreno Valley and a sergeant parent for the Moreno Valley Unified School District. She compiled her own social biography packet before she recognized it as such.

“When I found out that participatory defense has social bios as well, I [was] like, ‘Wow, I can really engage in that’ because I feel like that had power in the court proceedings,” Vick said.

By 2020, Vick’s case was dismissed and she resumed her work at Starting Over, helping families navigate the criminal justice system and empowering them to use their voice to support their loved ones.

“We’re not saying that public defenders or any attorneys are inadequate, or whatever,” Vick explained. “We’re here to support the community members and give the families the time that an attorney and a public defender cannot give.”

Lives saved by “time saved”

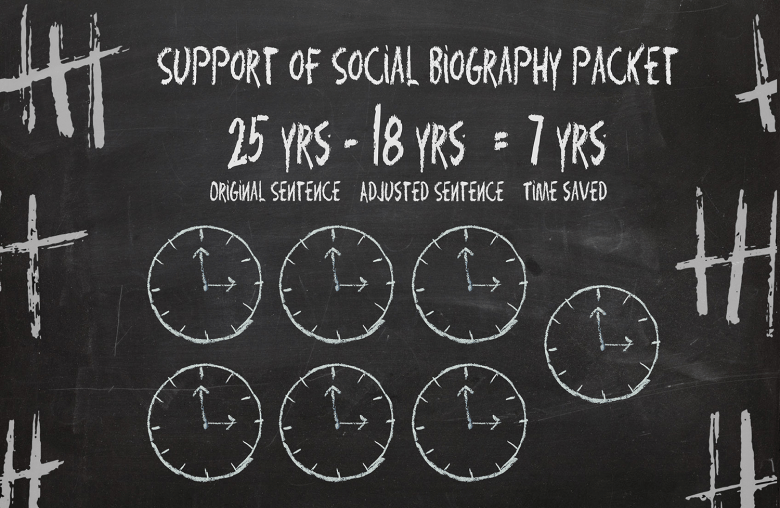

Since Starting Over began implementing and educating families on participatory defense, Jurado estimates that they have helped those facing charges save between 90 to 100 years. “Time saved” is a key measurement that allows hubs to track the impact they make. Time saved is calculated by taking the amount of time a person is facing at sentencing (“time served”) and subtracting that from the years they are actually sentenced to.

With approximately 30 hubs across more than a dozen states, the participatory defense network has calculated that together, they have saved 6,500 years of incarceration on behalf of people facing charges.

“We are dealing with a system of mass incarceration that has reduced justice to months in jail and years in prison and has often utilized life sentences as our only response to harm in our communities,” Khan said. “With participatory defense, public defenders, communities and people facing charges are given the opportunity to advocate for alternatives to incarceration or reduced incarceration.”

“I think seeing more people, seeing communities behind their loved one resonates with the courts as well,” explained Juardo.

While time saved is an important way to measure the impact of the participatory defense model, Khan said that it’s not the first benefit that comes to mind for him. Demonstrating the humanity of people in the system and those accused of harm, he said, has been the best thing that has come from practicing participatory defense.

Because participatory defense is unconventional compared to traditional handling of a criminal case, public defenders and lawyers are hesitant to embrace the model. That trepidation can be seen in Riverside County. Quarles said the model hasn’t been practiced much in places outside the Bay Area. In Riverside, said Quarles, everyone “tiptoes” around law enforcement, specifically the district attorney and sheriff’s offices.

“Participatory defense actually goes around that. We don’t even have to worry about the district attorney or the sheriff,” Quarles said. “[The model] focuses on how a person can lift up their loved one and humanize them so that the courts can see beyond the police report or the [court] filings and see who they are.”

Quarles said she believes that attorneys’ reluctance to engage in participatory defense can be attributed to busy schedules and unwillingness to discuss their clients. But, she believes that with this approach, they are building a more supportive and proactive public safety “ecosystem.”

Vick explained that participatory defense organizers work to bridge the gap between attorneys and communities, but oftentimes attorneys and public defenders mistake their efforts as an attempt to sabotage the case.

“We’re not here to overstep them. We’re not here to insult them and their education. We’re not saying that they’re incompetent — what we want to do is just be an extra resource to them and our community, as well as educate our community, giving [them] the support and love and the empowerment that they’re due,” Vick said.

Progress, not perfection

Steven Harmon has worked as a criminal defense lawyer for nearly 50 years and has spent nine years as a public defender in Riverside County. Several years ago, his office was contacted by Quarles about utilizing participatory defense. Since then, he’s started a program that allows Starting Over to recommend families to the public defender’s office who then matches attorneys with families who contribute information about their loved one.

“Participatory defense is just one aspect of the new wave of criminal justice reform. It’s just one part of the way the system and criminal defense should be enhanced and changed, and so on,” Harmon explained. “I’m very excited about the new prospects, the new ideas of criminal justice reform that are being utilized.”

Participatory defense doesn’t guarantee a favorable outcome, but using the model has been transformative. Communities and families are able to actively participate in advocating on behalf of their loved one against a system that easily disregards a person based solely on one mistake.

“It helps to show not just the community support, but show the judge who else this person is because all they see is a paper record that was provided to the court for the purpose of prosecution,” Quarles explained. “They don’t know that this person has been a single mom, struggling with poverty and addiction and had eight years of continued success, and relapsed and ended up catching another case.”

Harmon explained that it can be difficult to measure positive outcomes as a result of practicing participatory defense because there are many factors that are at play as it relates to positive or negative case outcomes.

“But that doesn’t mean that it’s not a worthy goal, and doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t continue to try it,” Harmon said. “And even if it doesn’t work, for instance, it’s still worth the effort and the try to the client and to the family — knowing that no stone was left unturned.”

With participatory defense, mitigating circumstances are brought to light in court. According to Khan, this model asks public defenders to step away from what’s only on paper and pushes them to connect with family members to understand more about the person who is being accused which will ultimately benefit their client.

Quarles said that she remembers a case in which a young person was facing 96 years for a charge. She couldn’t go into detail, but explained that social biographies are helpful during negotiations. The young person was facing 96 years imprisonment, but ended up with no time sentenced in adult court.

“I’m really grateful to De-Bug and Raj, in particular, for first creating [participatory defense] and sharing it with the community,” Quarles shared. “And, I can’t speak enough about the outcomes. I mean, to that person’s family, 96 years was a death sentence.”

Starting Over

Part 1: Every Exit is An Entrance

Part 2: Enter at Your Own Risk

Part 3: Proceed With Caution