Last Updated on December 4, 2023 by BVN

In the Beginning:

“[To] create a more secure, democratic, and prosperous world for the benefit of the American people and the international community.” The mission statement of the US Department of State established in 1789, resonates with the idea of the American dream, a dream lauded universally for more than three centuries. Yet, millions of Americans suffer from the impact of a history that disallows certain groups of people from experiencing prosperity.

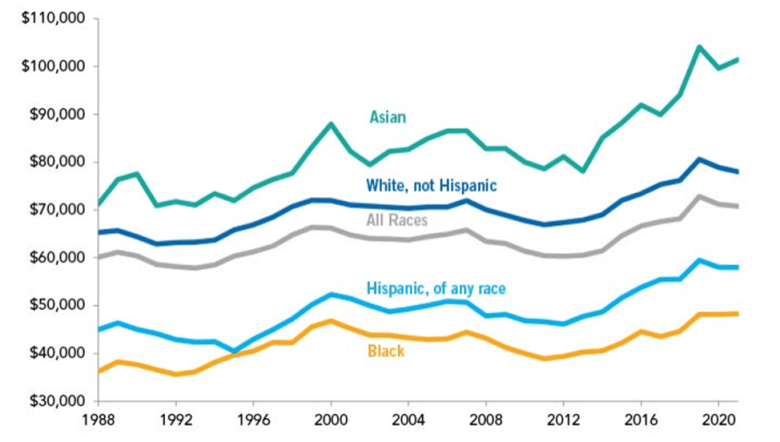

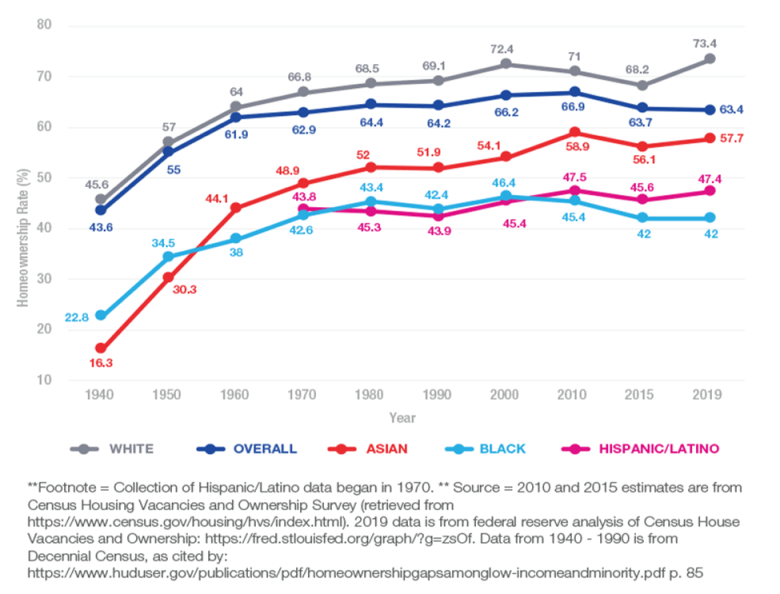

With the abolishment of slavery in 1865, came new and inventive ways to keep African Americans at a financial deficit, existing in an oppressive state that would hinder advancement in multiple areas of life. This includes one of the top foundational channels to building sustainability and intergenerational capital, the right to own real estate when and where one chooses.

One such establishment impacting traditional American life-building was the invention of redlining in neighborhoods across the country.

The impact of redlining left unhealed economic, health, safety, and educational bruises on communities nationwide that can still be seen today.

In the year 2020, 331.4 million people were reported to live in America, yet the US Census reports that 8.25 million people were identified as living in areas that were sectioned off as dangerous and redlined on maps around 80 years ago.

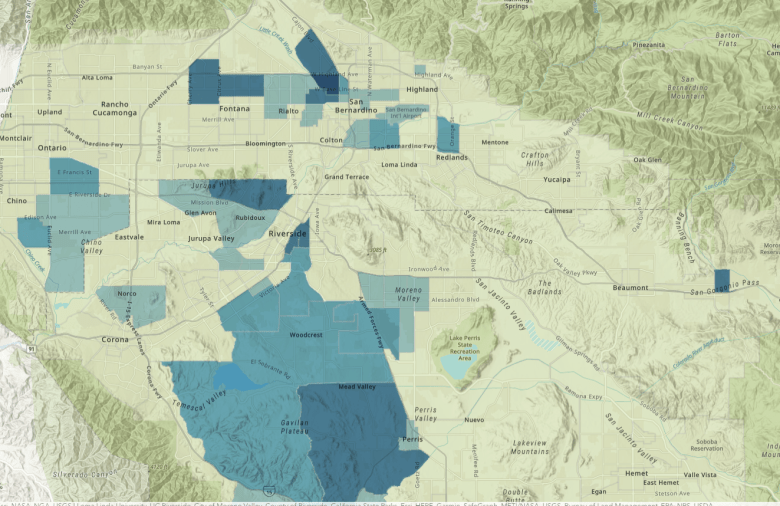

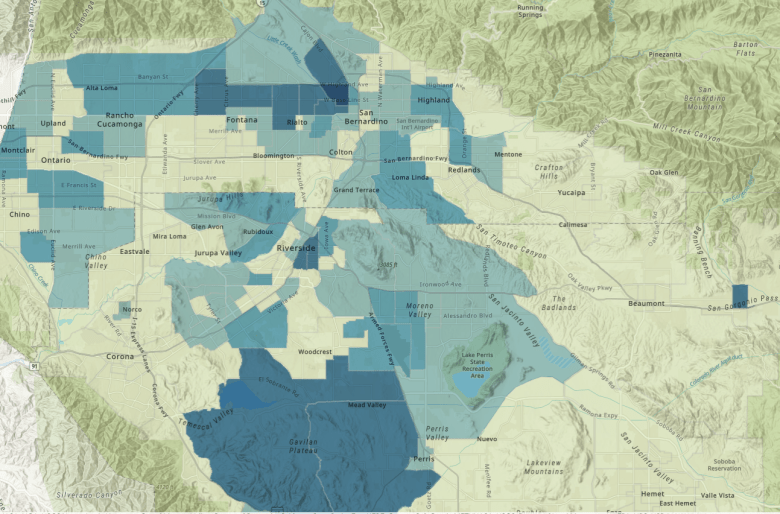

While many folks migrated west during the first and second waves of migration between the 1900’s and 1970’s for a better life, California still held in its fabric the stench of racist practices and was not exempt from the system of redlining. Deeper still, the Inland Empire – an urban and metropolitan area east of Los Angeles – carries its own rich history that embodied this practice. This history of segregation has contributed to ongoing racial inequalities and divides.

Redlining

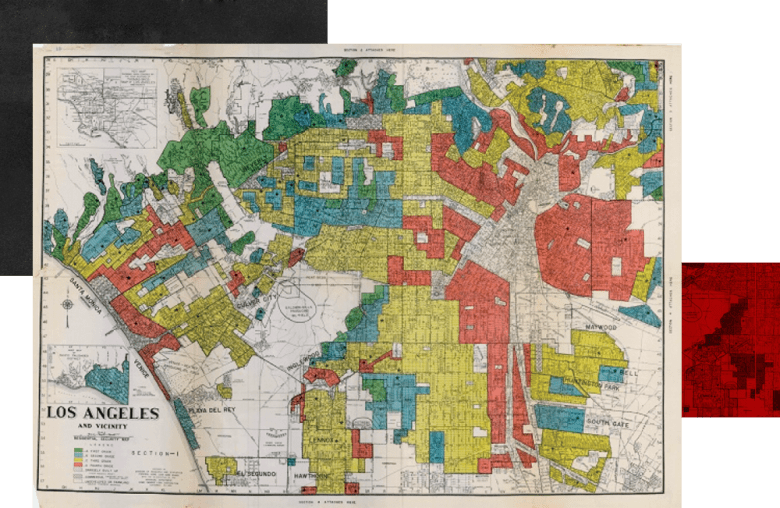

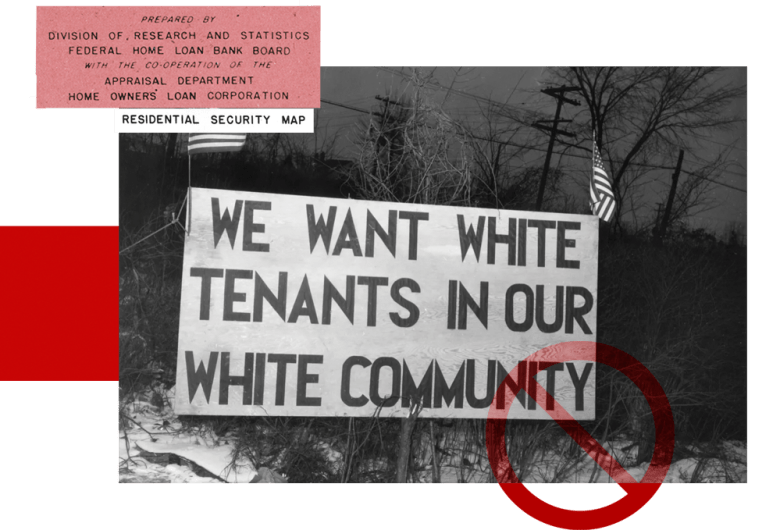

So, what is redlining? The term “redlining” was coined by sociologist John McKnight in the 1960s and derives from how the federal government and lenders would literally draw a red line on a map around neighborhoods that they would not invest in based on demographics alone. The federal reserve defines redlining as “the practice of denying a creditworthy applicant a loan for housing in a certain neighborhood even though the applicant may otherwise be eligible for the loan”.

In the 1930s the federal government began redlining real estate, marking “risky” neighborhoods for federal mortgage loans on the basis of race. This practice played a pivotal role in helping to create a segregated housing market.

In an interview with the Bridges That Carried Us Project, the late Frances Grice, a Civil Rights Activist who resided in the San Bernardino stated, “Every time I’d go to a real estate office, they’d send me back across the bridge….That was my first feeling that there was something wrong in this community. This beautiful valley that I’d seen, something was wrong. Then I noticed that all of the Black people lived on the other side of the freeway.”

Posed as a way to protect real estate investments, the actual practice of redlining became official in the year 1934 with the signing of the National Housing Act by President Franklin D. Roosevelt through the New Deal.

The National Housing Act included plans that were meant to help people with lower incomes. These initiatives included lower mortgages and longer payback periods allowing more individuals to buy homes. Through this, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) came into existence to ensure that people would not default on their homes, or as it was posed, security for investors.

This organization introduced maps that would section off various areas including ones considered hazardous, which were generally populated by Blacks and other minorities. These loans were denied to those living in hazardous or redlined areas, which resulted in owners abandoning the homes they couldn’t afford, not being able to perform renovations or upkeep, and more, creating more crime-ridden and poverty-stricken neighborhoods.

White flight

Enter the term “white flight”,]. While neighborhood conditions were worsening in these areas, white people would be convinced to flee to newer, suburban communities which excluded Black residents from buying homes. Real estate agents often encouraged the process of white flight through blockbusting, a practice where owners would be convinced to sell homes for cheap due to fear of another race or class moving in, then the homes would be sold at a higher rate.

“Realtors came in, scared the white people who lived there and then lured Black people into moving and they didn’t know they were part of a blockbusting campaign.” recalled the late Lois Carson, a San Bernardino resident who resided on 16th street and who organized against blockbusting.

When the National Housing Act was passed in 1934, examples of this practice could be seen in many major cities across the nation, including the Inland Empire where unofficial redlining took place in the 1920s according to University of Redlands’ Professor Jennifer Tilton.

As time moved on, many minorities were impacted by redlining, but in the Inland Empire, African Americans experienced the greatest impact. The decision to segregate Blacks and minorities through redlining created additional issues that have had a lasting impact such as poverty, health inequality, food apartheid, and education.

The Fair Housing Act

In the year 1968, the Fair Housing Act was passed by Congress, a policy meant to bring about equal housing opportunities. In the early 70s to 80s, the lines started to blur a little but were still visible.

(Source: courtesy of University of Redlands Professor and Author of the Building a movement on San Bernardino’s Westside, Jennifer Tilton)

Community

While the practice of redlining has disproportionately impacted Blacks, it should not be ignored that other minority groups also experienced housing discrimination. Those groups included Mexican Americans, Japanese Americans, and others, who in the Inland Empire, played a role in the area’s agricultural and railroad industry growth. Yet, tools like racial covenants and others that make up the ingredients of redlining, were used towards these groups as well.

In minority neighborhoods residents built and strengthened community bonds through various means, such as patronizing local businesses and enjoying recreational spaces. However, housing segregation often limited the potential for true community growth, as these communities often lacked the support needed for sustainability, including school quality and job opportunities. Yet, there remained the benefits of good neighbors, as described by former California Assemblymember Cheryl Brown, a resident of the Inland Empire since the 1950s.

“We had a wonderful wonderful neighborhood. Doctor Holder lived next door to us, across the street were two teachers, on the corner was a military family,” recalled Brown.

Initial movement into areas that were squared off may have posed some positives for residents as shared by Brown. In addition to places like the Community Settlement House on Bermuda Avenue in Riverside that provided services, housing segregation and redlining restricted many minority homeowners from permanent ownership or even being able to repair and improve their properties. This continued to result in crime and poverty, which may have impacted social interactions.

The importance of education in building community

Education is one of the key spaces where community connection begins within neighborhoods, thus highlighting the importance of quality schools for a positive social impact on the individual. In redlined neighborhoods, the decline in economic access created a decrease in home value, which, in turn, resulted in less financial support (including property taxes) being available for schools in the neighborhood. The status of local schools would impact the value of homes and vice versa in the red-lined communities, therefore, creating a never-ending downward spiral in segregated areas, many of which became impoverished.

The lack of economic mobility posed a problem in general for homeowners’ ability to accrue generational wealth and maintain and build the community they had moved into, a problem that persists to today. The exit of some homeowners or the nonexistence of wholesome upkeep, resulted in more people leaving or those who stayed, experiencing the decline in their neighborhood. However, the exit of some residents would result in other issues as they looked to relocate to other neighborhoods.

The Mill School, located in a neighborhood in South San Bernardino known as the Valley Truck Farms, was a thriving school in a racially mixed neighborhood, but as the Black population increased, white flight “sprouted wings” and accelerated in the 1940’s when the school hired its first Black teacher, Dorothy Inghram.

The lack of economic mobility posed a problem in general for homeowners’ ability to accrue generational wealth and maintain and build the community they had moved into, a problem that persists to today. The exit of some homeowners or the nonexistence of wholesome upkeep, resulted in more people leaving or those who stayed, experiencing the decline in their neighborhood. However, even the exit of some residents would result in more issues as they looked to relocate to other neighborhoods.

For the few who successfully moved in where covenants against Blacks were in place, some experienced cross burnings and bombings, used as tactics by racists to scare them off. Some would choose to stay, while others would decide that it was not worth it.

These kinds of displays along with the many other resistances that were met, began the longstanding historical impact on the Black community’s efforts to establish sustainable infrastructure and wealth.

What was done?

Many civil rights groups and activists did their best to combat the issues that arose from housing segregation, as well as to work to dissolve redlining altogether. Such actions were often birthed at local Black churches, as Black churches are historically the epicenter of community connection, resistance, demands for change, and growth. The church also serves as a place for solace and help, networking among Black professionals, and community building.

An example of this were the comments made by the Rev. J. H. Wilson, minister and leader of the Black community’s oldest place of worship in Riverside, the Allen Chapel African Methodist Espicopal Church (12th and Howard) during the opening of Mercantile Hall in 1905. Speaking about the importance of securing political recognition and economic advantage through education and self reliance he said, “[S]eparation of the races on planes of equality is more valuable than a lot of sentimental platitudes resulting in actual race discrimination.”

Recognizing homeownership as pivotal to economic growth and advantage, members of the Black community fought against redlining in a number of ways including organized demonstrations.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had chapters where leaders often pushed back against local covenants and created community networks. One such example in the Inland Empire was that of the NAACP Youth Council which was active in the 1950s and met in Johnson Hall previously on the corner of 9th and Wilson in Riverside. Protests were also organized to fight against segregation in schools, one is cited from San Bernardino’s Congress of Racial Equality group in 1963, where leaders were arrested, but many more protests would continue during this era.

Other actions were taken by residents to create community and build up the neighborhoods while also looking to create opportunities for integration into better neighborhoods down the line.

A lingering impact

The practice of redlining, which was only officially in play for the better part of 30 years, is still felt within Black communities. Many see the “Martin Luther King Blvd. streets” as the marker for these underprivileged Black neighborhoods, but these areas are simply the outcome of a practice that intentionally restricted a certain sector of people from accessing the American dream.

As we dive more deeply into the history of redlining in the Inland Empire, we will also begin to look at what solutions are being put in place, almost a full century later, to continue combating the practice of redlining and its consequences.

Because redlining became illegal with the signing of the Fair Housing Act, many assumed that the issues resulting from it, as well as the segregated neighborhoods, were dissolved. But, practices continued that perpetuated the existence of limited expansion beyond redlined neighborhoods for several decades.

Interestingly, “The gap in homeownership rates between white and Black families is larger today than it was before the passage of the Fair Housing Act of 1968,” noted the US Justice Department in an October 2021 press release.

In 2021, the United States Justice Department released a statement regarding a new initiative being put into place to address the existing impacts of redlining. The new initiative aims to work with the Civil Rights Division’s Housing and Civil Enforcement, as well as US Attorney’s offices to create a plan that provides equal opportunities for homeownership and mortgage credit. While this may seem similar to the Fair Housing Act, the statement provides more details on how this will be implemented.

This initiative does not provide a solution that completely and immediately dissolves the issue, yet it indicates that the work of many to bring awareness to its constant existence, community involvement, in addition to the interest and work of Civil Rights activists are finally being heard in spaces where real change is being made.

For a more comprehensive understanding of how redlining impacted Blacks and other people of color in the Inland Empire, watch for Part 2 of The Thick Redline series, The Line Runs Through Here.

This project was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library.

References:

Maps produced by A People’s History of the Inland Empire with data from Ruggles, Steven, Sarah Flood, Ronald Goeken, Megan Schouweiler and Matthew Sobek. IPUMS USA: Version 12.0 [dataset]. Minneapolis, MN: IPUMS, 2022. https://doi.org/10.18128/D010.V12.0

Video Citations (and Frances Grice quote from)

Bridges That Carried Us Over Project: Documenting Black History in the Inland Empire https://www.csusb.edu/special-collections/projects/bridges-carried-us-over-project

Blockbusting. (n.d.). Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/blockbusting

Census Bureau (U.S.) Decennial Census P.L. 94-171 Redistricting Data. (2021, September 16). Retrieved November 20, 2022 from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/rdo/summary-files.html

Fair Housing Act – federal reserve. Federal Reserve. (n.d.). Retrieved November 12, 2022, from https://www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/supmanual/cch/fair_lend_fhact.pdf

Frances Grice Oral History. Bridges That Carried Us Over Project: Documenting Black History in the Inland Empire, Pfau Library CSUSB at https://www.csusb.edu/special-collections/projects/bridges-carried-us-over-project

Gibbons, J. (2015). Does Community Connection Vary between Different Segregated Neighborhoods? Population Association. Retrieved November 27, 2022, from https://paa2015.populationassociation.org/papers/152134

Gudis, C. (2022, September 25). Claiming Our Space. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e441b082dd8646cfa48fd5017730e7e9

Hayes, A. (2023). What is Redlining? Definition, Legality, and Effects. Investopedia. Retrieved February 1, 2023 from https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/redlining.asp

Justice Department announces New Initiative to Combat Redlining. The United States Department of Justice. (2021, July 6). Retrieved November 28, 2022, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-new-initiative-combat-redlining

Meier, H. C. S., & Mitchell, B. C. (2022, July 8). Tracing the legacy of redlining: A new method for tracking the origins of housing segregation” NCRC. National Community Reinvestment Coalition. Retrieved November 8, 2022, from https://ncrc.org/redlining-score/#:~:text=Persisting%20segregation%20%E2%80%93%208.25%20million%20people,belonging%20to%20a%20minority%20group.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). White flight definition & meaning. Merriam-Webster. Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/white%20flight

Perry, A. M., & Harshbarger, D. (2022, March 9). America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them. Brookings. Retrieved November 8, 2022, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/#:~:text=Together%20with%20racially%20restrictive%20housing,improvements%20to%20homes%20already%20owned.

Person. (2008, April 18). Housing and Education: The inextricable link: 11: Segregation: Tayl. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved November 24, 2022, from https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.4324/9780203895023-11/housing-education-inextricable-link

Tilton, J. (2022, October 20). Building a movement on San Bernardino’s westside. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e2431587394f4f19b1afd4221881fa20

Tilton, J., Gomez, D., & Costello, M. (2022, November 30). Fighting School segregation in San Bernardino. Fighting School Segregation in San Bernardino. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/13d98519b5e2499fa4c6c9eaf606c585

Tilton, J. (2023). Color lines in San Bernardino: Mapping Housing Segregation on San Bernardino’s Westside. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/cc8794c1eb9041f48b9f43f929841c56

U.S. Census Bureau quick facts: United States. (2020, April 1). Retrieved November 25, 2022, from https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/POP010220U.S. Department of State. (n.d.). Mission. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved November 26, 2022, from https://2009-2017.state.gov/s/d/rm/rls/dosstrat/2004/23503.htm#:~:text=Create%20a%20more%20secure%2C%20democratic,people%20and%20the%20international%20community

Centerpoint: The Thick Red Line

Part 1: The Line Begins Here: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire

Part 2: The Line Runs Through Here: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire