Last Updated on December 4, 2023 by BVN

Where The Inland Empire Story begins

The Inland Empire was one of the major epicenters of agriculture in the 19th century, encompassing two counties, San Bernardino and Riverside. Through the growth of industrialization and the two world wars, the Inland Empire held its own in the fabric of California as the state’s economic engine kept pace with time.

Many accounts tell the story of its beginnings, the popular owners of citrus groves, and even Booker T. Washington’s visit in the early 1900s. However, the diverse stories of those who helped weave the identity of this community and the discrimination they faced are often missed.

The establishment of housing segregation, while harder to document in the Inland Empire, carried the same traits as those marked in major urban centers like Los Angeles.

Housing segregation has various impacts, including interference with community connection, education, and financial longevity. In light of this, it is important to understand its historical imprint on Southern California’s inland region.

Beginning Settlement

Native Americans inhabited the Inland Empire for thousands of years prior to both Spanish and American Colonization. According to the web application Native Land, the Inland Empire was once home to the Tongva, the Payómkawichum (Luiseño); the Kizh; the Cahuilla, and the Yuhaviatam/Maarenga’yam (Serrano) tribes, whose presence date back to between 3500 and 5000 years. All of these tribes survived and are federally recognized today, including the Pechanga, San Manuel, Cahuilla and others.

In 1851, a group of Mormon settlers arrived from Utah and founded what would become San Bernardino.

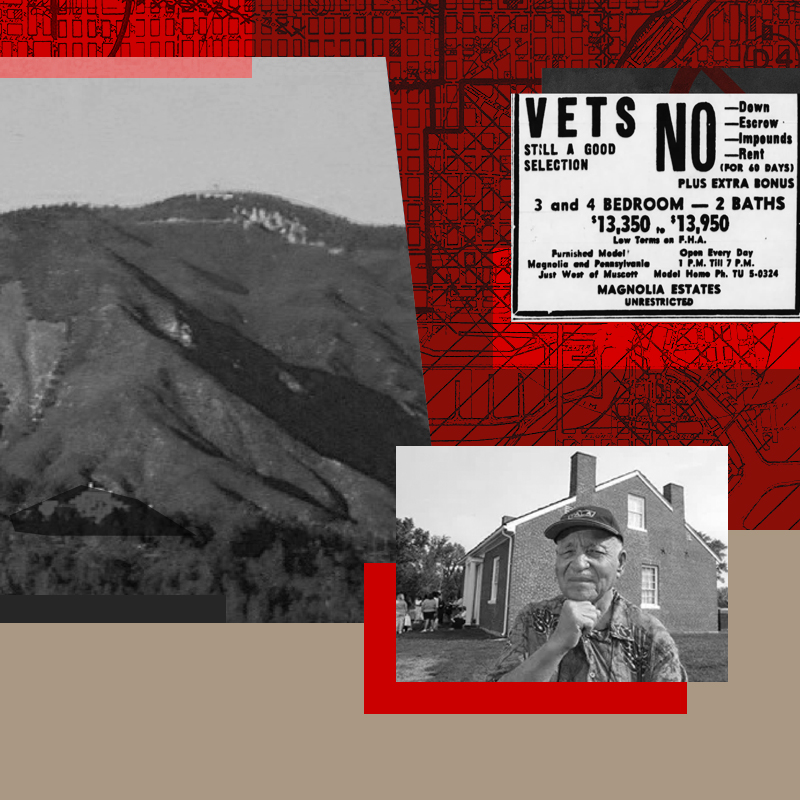

According to University of California, Riverside professor and author, Cathy Gudis, the first group of African Americans, though small, came with this settlement. Included among them was the late Biddy Mason, an enslaved Black woman who eventually sued her owner, Marion Smith, and in 1856 won her freedom. She would go on to become one of the wealthiest real estate moguls in California by the time of her death in 1891.

The community of settlers had a shared network, traveling to and from Los Angeles and the Inland Empire. The agricultural industry in the late 18th century meant the need for land development, which included new irrigation methods.

Many of the citrus groves were hiring Latino workers, but not as many African Americans. Hence, African Americans like the late Israel Beale, would own their own citrus groves and then clear land for others in the surrounding area for new crops. It should also be noted that available jobs were different for each group.

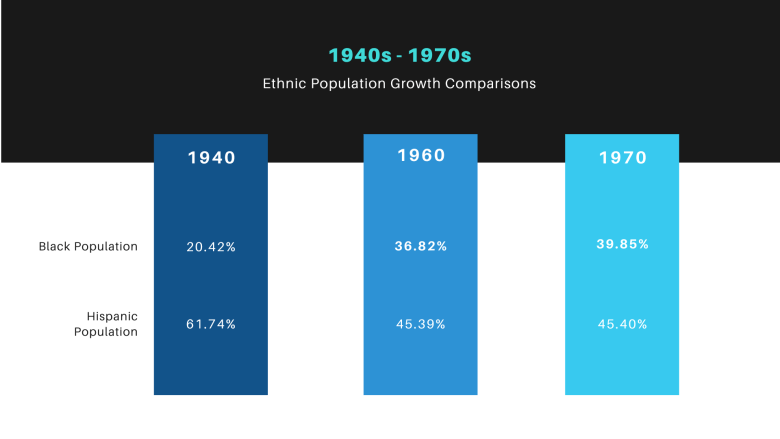

In the early 20th century through the 1940’s, Latinos were the larger part of the population residing in the heart of Riverside’s Eastside. However, by the 1960s and into the 1970’s, the Black and Latino populations were growing at a relative pace.

The Great Migration in the early 1900’s showed a large population of Blacks leaving the South and going mostly North, however, a small population arrived in the Inland Empire and joined the even smaller pre-existing community. Soon, the Black and Latino populations began to swell on the eastside of San Bernardino.

Migration of Blacks from the South by Decade

The Great Migration, that began in the early 1900s and spanned through 1930’s, was followed by a second wave of migration spawned by World War II. During the initial migration, a large population of Blacks left the South going mostly North, however, a small number do make their way to California, with some settling in the Inland Empire, joining the even smaller pre-existing community. A greater number of Blacks arrived with the second wave of migrants in the wake of World War II. (source: depts.washington.edu Mapping Social Movements Project. America’s Great Migration Project).

During this time, Blacks held a strong sense of entrepreneurial spirit and the rhetoric from the pulpit in Black churches on Sundays often reflected and encouraged this. Many early 20th century migrants were able to purchase property and become homeowners and business owners. Those who came later, would settle and become become part of a growing Black community on the Eastside of Riverside. This area, however, would later be among those redlined during housing segregation.

The greatest influx of Blacks within the Inland Empire was seen with the historical marker, the Second Great Migration, that began in the 1940’s through 1970’s. (See the Migration of Blacks from the South by Decade, above). Whereas with the first migration, many Blacks went North, this one began to expand more notably westward alongside historical events like World War II and the rise of industrialization. (See migration map above).

Housing Segregation & Redlining:

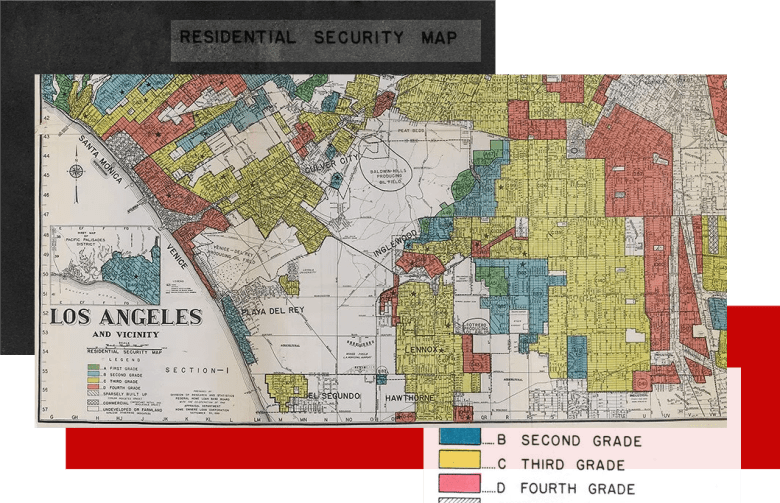

Because these migrations led to big cities like Los Angeles, there are clear markers on maps from agencies like the Home Owners Loan Corporation that show which areas were cut off and redlined, thus restricting housing access for Blacks, Latinos and other minority groups.

The Inland Empire, however, does not have official redlining maps, yet various informal practices enforced housing restrictions based on race and resulted in redlining of the area, were still implemented in the region. Some of these restrictions included covenants and gentlemen’s agreements.

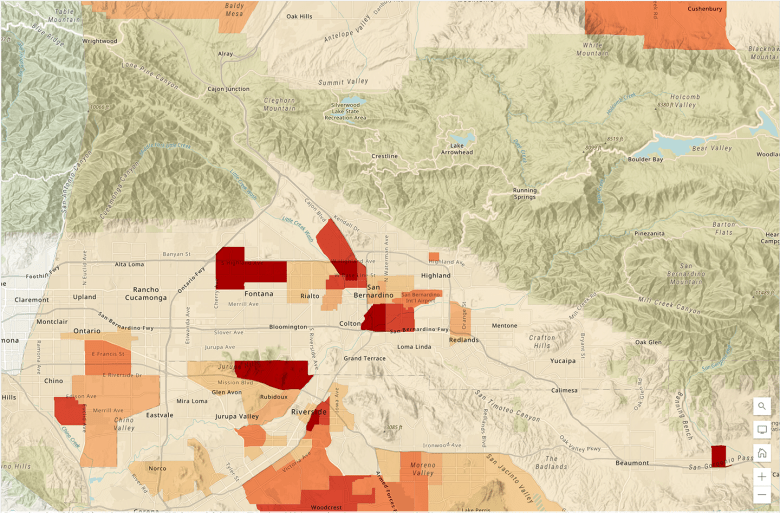

Inland Empire’s Black Population in the 1970’s

Although no official maps exist of redlining in the Inland Empire, the various practices that enforced housing restrictions based on race and resulted in redlining of the area, were still implemented in the region including covenants and gentleman agreements. (Source: Map showing Black population in 1970 in San Bernardino Riverside produced by a People’s History of the Inland Empire for Black Voice News).

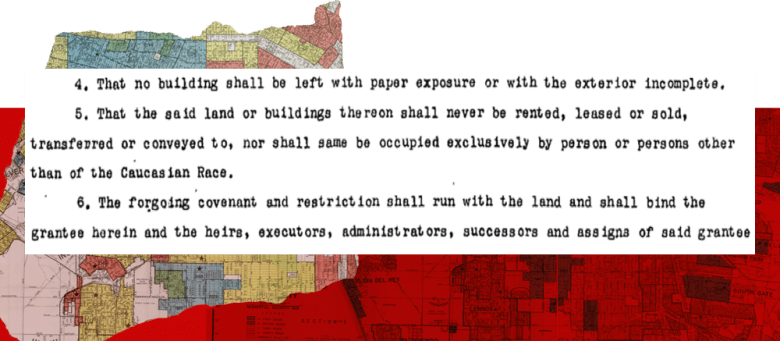

Covenants

In the 1950s when individuals like the late Dr. Barnett Grier, a physicist that worked in the defense industry, and other Blacks with advanced degrees moved into the inland region, they began to shake things up. At this same time, the practice of covenants began. These were put into place as deeds on homes that were used to restrict ownership on the basis of religion or race. The language would use exclusionary phrases, such as, “restricted to the white race” or “highly restricted” indicating that the housing would only be available to individuals and families who had the specified attributes. This was in an effort to “create exclusively white spaces” in the Inland Empire.

Gentlemen’s Agreements

Gentlemen’s agreements, where realtors, homeowners, or loan officers would agree to not sell or provide loans to nonwhites, were also made to ensure that areas would remain exclusively white. So strong were these efforts, that there are accounts of white homeowners going to the city council to stop Latino homeowners from moving to all-white areas.

“Property owners on both sides of 9th Street had agreed to restrict homebuyers to “whites only.” The city agreed to help their efforts by investing in improving sewers, curbs and sidewalks in the all white neighborhoods to increase home values, which would create another barrier for Black and Mexican homebuyers.”

Color lines in San Bernardino: Mapping Housing Segregation on San Bernardino’s Westside by Jennifer Tilton 2023

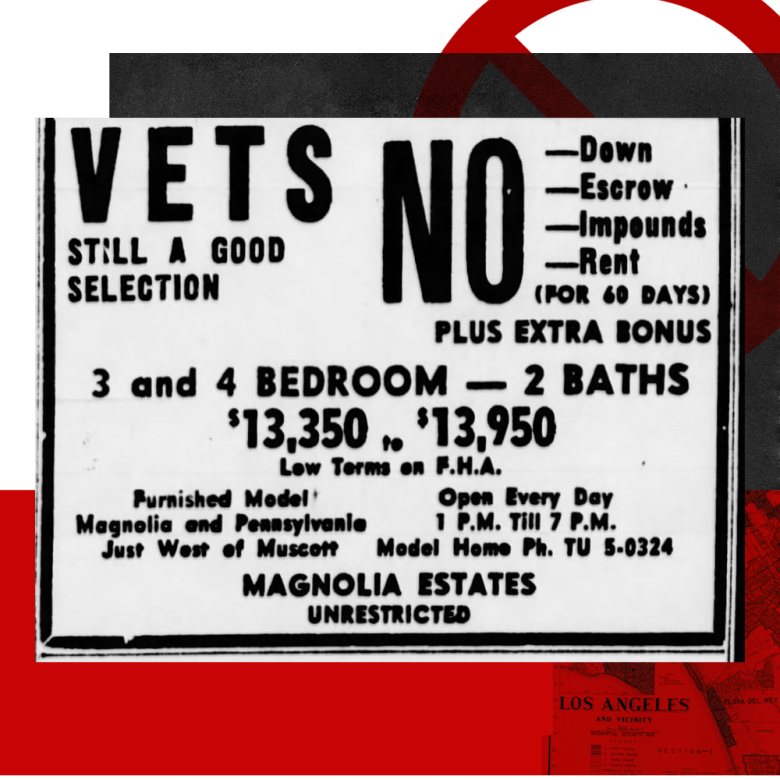

The practice of covenants extended beyond restricted access to average citizens and reached even Black GIs. Covenants would show better loan rates, fewer restrictions, and beautiful housing for GIs, but would follow with language that either overtly or covertly restricted access to Blacks or other non-whites.

In 1948, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in the case of Shelly v Kraemer that the government could not enforce restrictive covenants. However, the actions of the government did not stop the white community from continuing restrictive practices. Covenants and prohibitions were still in existence by the actions of white homeowners and other community members who would take extreme measures to keep their neighborhoods all white.

Violence Ensues

It should be noted, that most Blacks looking to move into all-white areas held higher degrees of education than those already inhabiting these areas and would therefore have great arguments for community contribution, according to University of California, Riverside professor and author, Catherine Gudis. Therefore, housing restrictions would be the easiest way to keep Blacks and other minorities out.

Aside from the covenants in place, white community members used violence to scare away nonwhites from moving into the communities they had deemed restricted.

In 1946, the late O’day Short found property by crossing the color line in Fontana, and was met with fatal violence. After being subtly threatened by the local sheriff, Short moved in with his wife and two young children, just weeks after moving, their home was set on fire, killing both of his daughters and his wife. Short died not long after (Tilton 2022).

This was not the only violent act that took place to keep Black and Latino families away. Many decided they did not want their families in these areas and would resort to moving back to unrestricted areas. These violent events continued through the early 1960’s, such as the story of Lt. K.G. Jefferson a UCLA Physics graduate, whose home was bombed before he was able to move in.

Blockbusting and White Flight

After World War II, some Blacks began to push past the color lines, building homes, then helping to bring others into the neighborhoods. While some white homeowners or community members would resort to violence, most would leave and move to the suburbs.

So what is white flight? The term “White Flight” comes from an exodus that happens when white residents leave a neighborhood en masse because of the entrance of Black residents.

Coinciding with White Flight enters the practice of “Blockbusting” which happened when owners were persuaded to sell their properties for lesser amounts because of fear that another ethnic group would move in. These two practices would often go hand in hand, when a Black family or two moved into an area, real estate agents would use fear tactics to convince white homeowners to sell their property at a lower rate. Subsequently, the agents would then sell these properties at higher rates to incoming non-white residents.

Some Blacks in the community would organize to stop the process of blockbusting, such as the late Lois Carson.

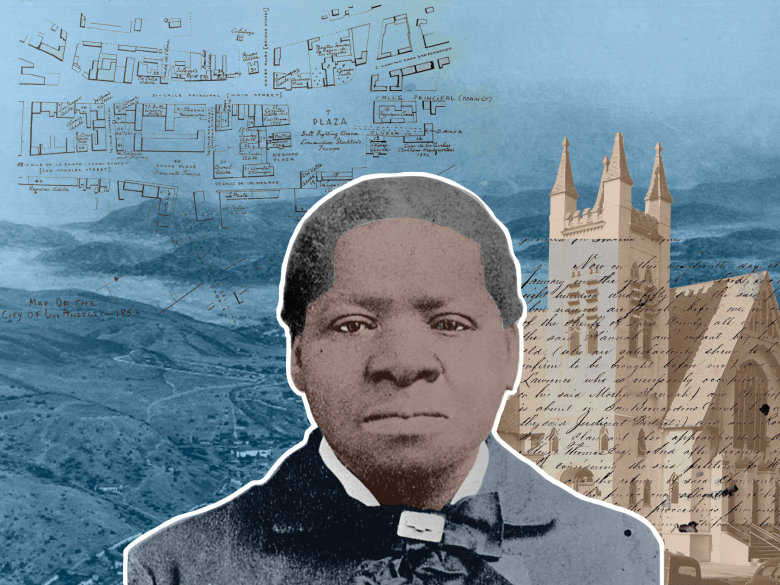

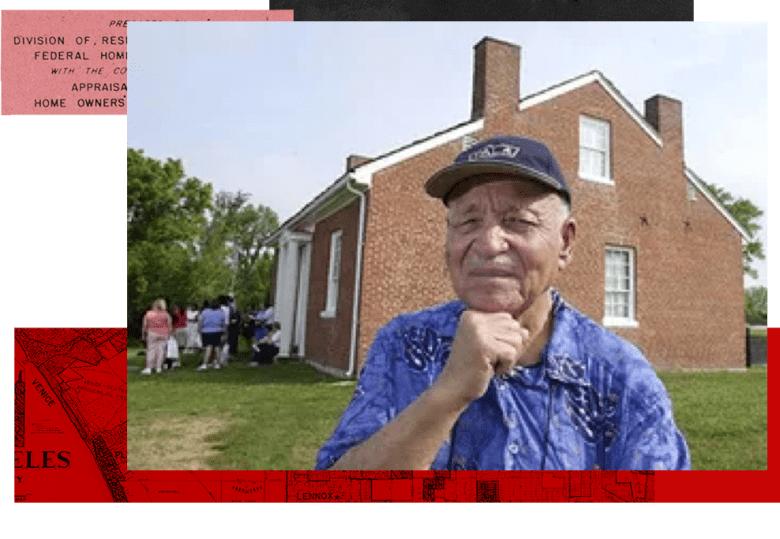

The late Lois Carson discussing the practice of Block Bustingin the Inland Empire. (Source:Bridges That Carried Us Over Project, CSUSB Pfau Library https://scholarworks.lib.csusb.edu/bridges/ ).

Unfortunately, these efforts would prove unsuccessful and the result would be the strengthening of racial segregation, only in different neighborhoods.

Real Estate Agents & Steering

As Black and Latino families began successfully crossing color lines into white neighborhoods, real estate agents would often guide prospective Black homeowners into areas predominantly inhabited by Blacks and Latinos. Some of these efforts were subtle, while others were obvious. Such as the story of the late Dr. Henry Holder, who looked for property near the Patton State Hospital in San Bernardino County where he worked.

“But when he met with a real estate agent to discuss options, the agent encouraged him to look for homes in the Muscott St. area west of the freeway. The San Bernardino Sun reported on September 5, 1965, that “after a few tries, he gave up on the option of living near work and bought a home on the Westside [of San Bernardino].”

While there were Black real estate agents like Talmage Hughes, who helped sell the Magnolia Estates, they often worked within the already segregated confines, this only encouraged and helped to cement the segregation of the area. This led to a 70% Black community by the 1970s, for example, within the borders west of Mount Vernon, north of Ninth Street and extending up to Highland to the wash in San Bernardino.

Conclusion:

The data and accounts from residents who resided in the Inland Empire during this time make it clear that redlining in this community was a large part of the history of its formation and growth. Like other individuals who lived through an era when racially discriminatory practices were overt, the Inland Empire’s Black residents tell a story of building resistance against redlining at the height of its existence. Their stories draw a closer look into the origins of systemic racism in the area and can be referenced to explore the current state of the Inland Empire.

Follow this story in Part 3 of The Thick Red Line, The Line Keeps Extending Through Time

This project was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library.

References:

Education, N. G. (2012). The Second Great Migration. National Geographic Education. Retrieved December 8, 2022, from https://media.nationalgeographic.org/assets/file/african_american_MIG.pdf

Gregory, J. (n.d.). 2nd Great Migration. University of Michigan. Retrieved December 2, 2022, from https://faculty.washington.edu/gregoryj/2nd%20great%20migration_James%20Gregory.pdf

Gudis, C. (2022, September 25). Claiming Our Space. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e441b082dd8646cfa48fd5017730e7e9

Langley, B. (2022, December 20). Interview with Professor Catherine Gudis. personal.

Langley, B. (2022, November 22). Interview with Jennifer Tilton. personal.

Meares, H. (2017, March 1). Biddy Mason was one of La’s first black real estate moguls. Curbed LA. Retrieved December 13, 2022, from https://la.curbed.com/2017/3/1/14756308/biddy-mason-california-black-history

Smigel, Z. (2022, December 6). Steering in real estate definition. Real Estate License Wizard. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://realestatelicensewizard.com/steering/

Tilton, J. (2022, October 20). Building a movement on San Bernardino’s westside. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e2431587394f4f19b1afd4221881fa20

Tilton, J., Gomez, D., & Costello, M. (2022, November 30). Fighting School segregation in San Bernardino. Fighting School Segregation in San Bernardino. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/13d98519b5e2499fa4c6c9eaf606c585

Tilton, J. (2023). Color lines in San Bernardino: Mapping Housing Segregation on San Bernardino’s Westside. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/cc8794c1eb9041f48b9f43f929841c56

Yarbrough, B. (2021, November 22). Here are the 13 Native American tribes in the inland empire recognized by the Federal Government. San Bernardino Sun. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.sbsun.com/2021/11/19/here-are-the-12-native-american-tribes-in-the-inland-empire-recognized-by-the-federal-government/#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20crowd%2Dsourced,%2FMaarenga’yam%20(Serrano)

Centerpoint: The Thick Red Line

Part 1: The Line Begins Here: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire

Part 2: The Line Runs Through Here: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire

Part 3: Lines Keep Extending Through Times: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire