Last Updated on December 4, 2023 by BVN

Today, rice stands as an ancient, but prominent, cross-cultural staple grain with a global history traceable for thousands of years.

Whether you are enjoying paella, jambalaya, cơm chiên, or another rice centered dish, this grain serves as a food bridge across centuries, continents and cultures.

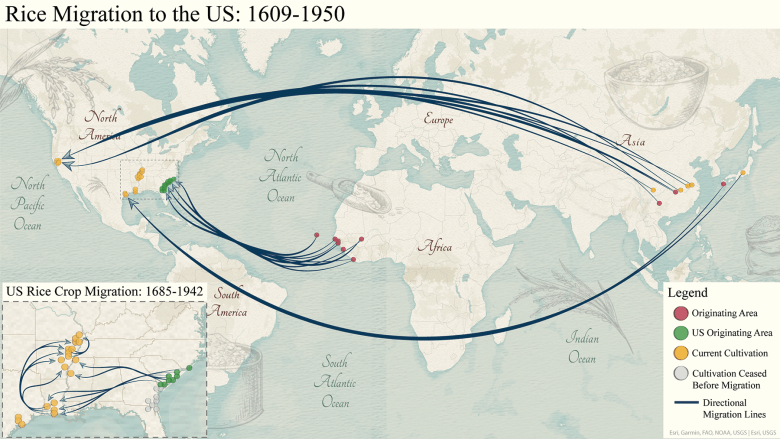

The earliest traces of rice identified by archaeologists begin with the Oryza sativa grain, found in China’s central and eastern regions between 7000–5000 BCE.

Later came the cultivation of African wet rice, Oryza glaberrima. The grain is connected to communities along the Niger, Sine-Saloum, and Casamance Rivers from approximately three thousand years ago.

Rice was first identified in the U.S. in the 17th century.

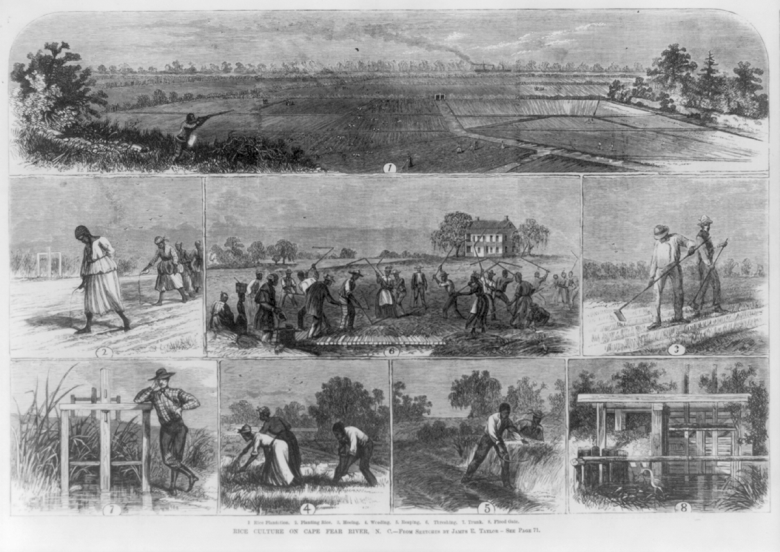

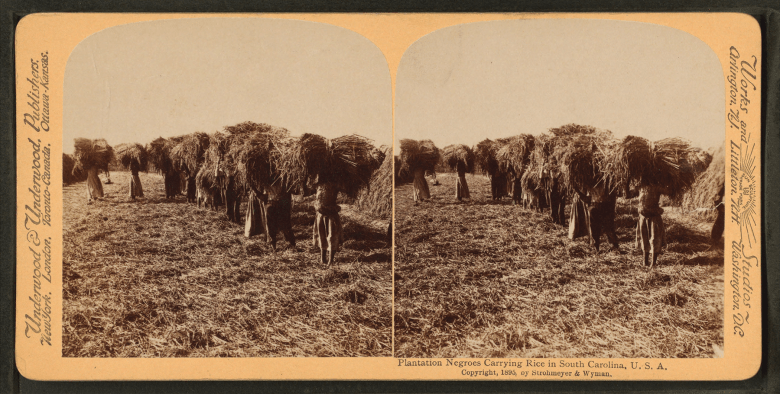

Until the cusp of the 20th century, rice production boomed in the marsh coastal areas of the American Southeast, primarily in South Carolina and Georgia. Historical records indicate that colonizers within these regions sought to enslave West Africans due to their knowledge of rice production throughout the 17th century.

Before Cotton was King

On July 11, 1785 the Charleston Evening Gazette advertised, “a choice cargo of Windward and Gold Coast Negroes, who have been accustomed to the planting of rice.”

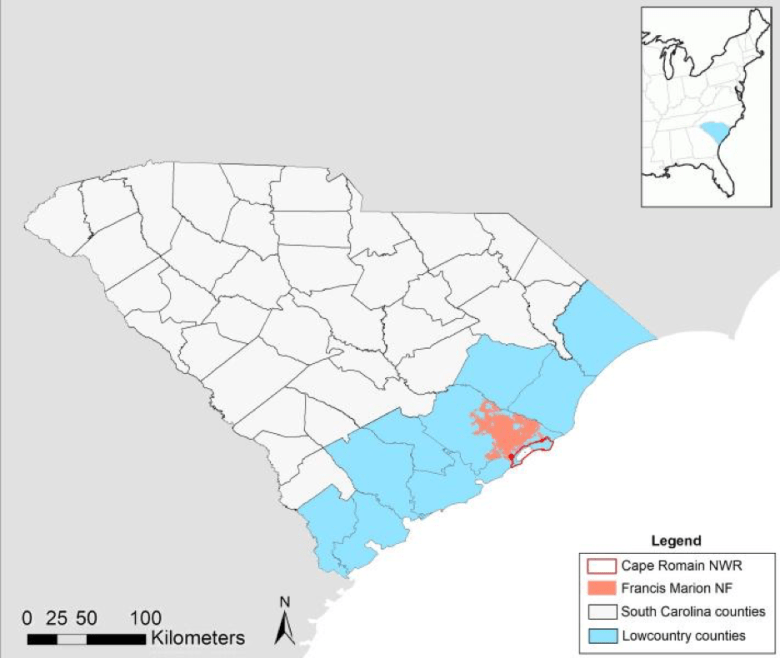

While a portion of the red-colored rice found in early South Carolina was the African Oryza glaberrima grain, which may have arrived on slave ships, rice plantations quickly adopted two varieties of Asian Oryza sativa: the “Carolina White” and “Carolina Gold.” Rice cultivation was centered in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, a geographic and cultural region along the coast.

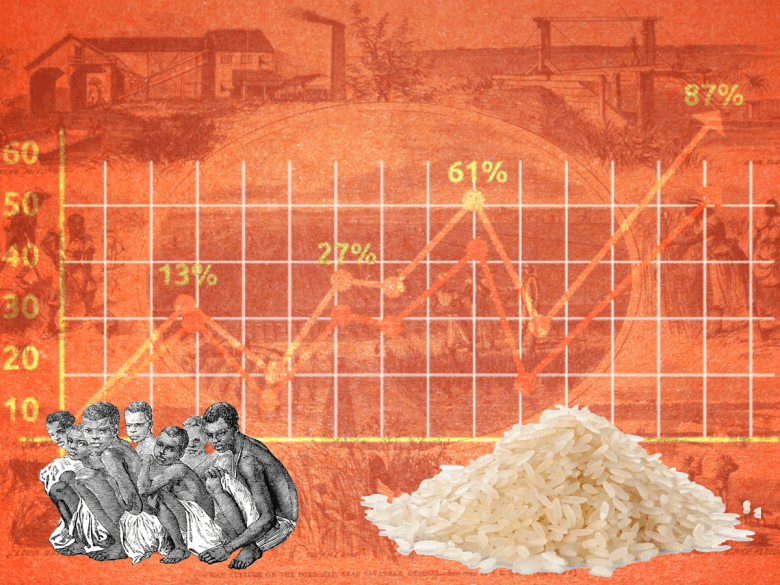

Forty percent of all American enslaved Africans passed through the Port of Charleston. In the 17th century, individuals from the African regions that cultivated rice (the Upper Guinea Coast, Senegambia, and the Windward Coast) were purchased at the highest amounts by rice plantation owners from Georgetown and Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia.

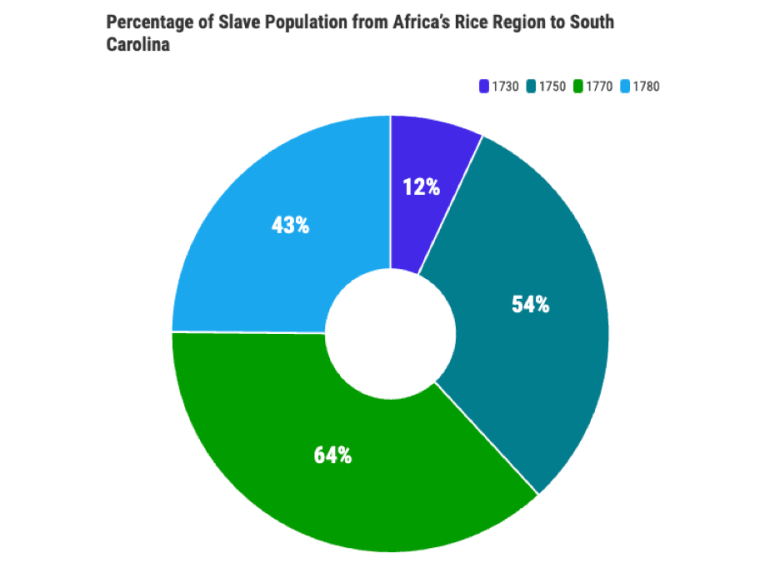

According to a report produced by Jean M. West “Rice and Slavery: A Fatal Gold Seede,” in the 1730s, roughly 12 percent of South Carolina’s enslaved Africans were from the center of Africa’s rice-production region.

By the mid-17th century that number rose to 54 percent, and reached 64 percent in the 1770s before receding in the 1780s and averaging 43 percent in the 18th century.

A Dangerous and Lethal Crop

Historians say that rice cultivation in the American South was not only dangerous, but often lethal. Inadequate living conditions, nutrition and medical treatment posed serious risks to the enslaved coupled with deadly infections such as malaria and yellow fever. The land also presented the dangers of venomous snakes and alligators which killed nearly a third of the enslaved within a year in Lowcountry South Carolina. In this same region, less than one in ten children lived to age sixteen, according to a report published by the University of Minnesota Press.

In the 1770s, an enslaved African could produce rice worth more than six times his or her own market value within a year, making the high rate of death still economical for plantation owners.

Under these dangerous conditions, a majority of owners fled their plantations during the summer months, leaving the enslaved to harvest rice themselves under a task labor system. In this system, they were assigned tasks that often amounted to ten hours of work a day. Once the work was completed to an overseer’s satisfaction, they were allowed to spend the remainder of the day as they chose. Historians say the nature of this system provided more autonomy for the coastal southern enslaved populations than those in other regions who harvested different crops.

“It’s [the system of cultivating rice] something that can make you feel empowered. It’s enough to make you feel like you have some self-esteem that you have the things that slavery is trying to do away with. Being in these complex, socially, hierarchical slave communities can give one a sense of self and place and belonging, and purpose,” said University of California, Riverside Professor of History Natasha McPherson

The majority of the enslaved population in the Southeastern region originated from Angola. Their descendants are known as the Gullah people. “Gullah” is believed to be derived from the pronunciation of Angola during that period, “N’Gulla.” Some historians attribute the isolated nature of the task system as a space where culture and language not only survived, but was passed down. Today, American English contains words of the Gullah origin, including “yam,” “okra” and “tote.”

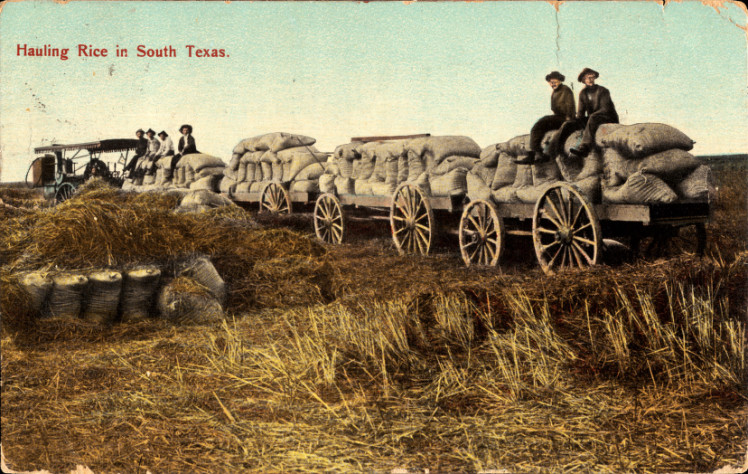

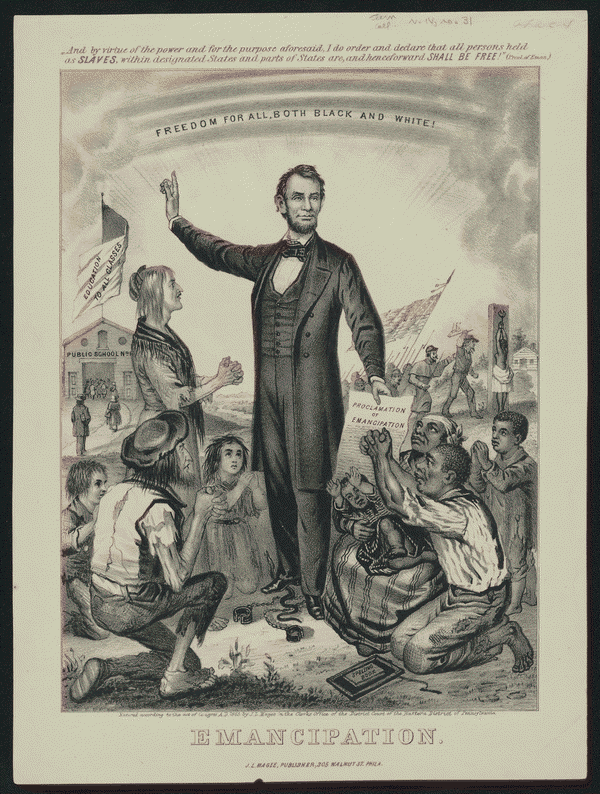

In the mid-19th century, rice was introduced to Louisiana and Texas. Shortly after, in 1865, came emancipation. The end of slavery meant an end to slave labor which quickly reduced rice production’s profitability. Rice production fell steeply. This, in combination with a series of hurricanes that devastated South Carolina in 1893 and damaged levees, ceased rice production within the region.

Innovations and Rice

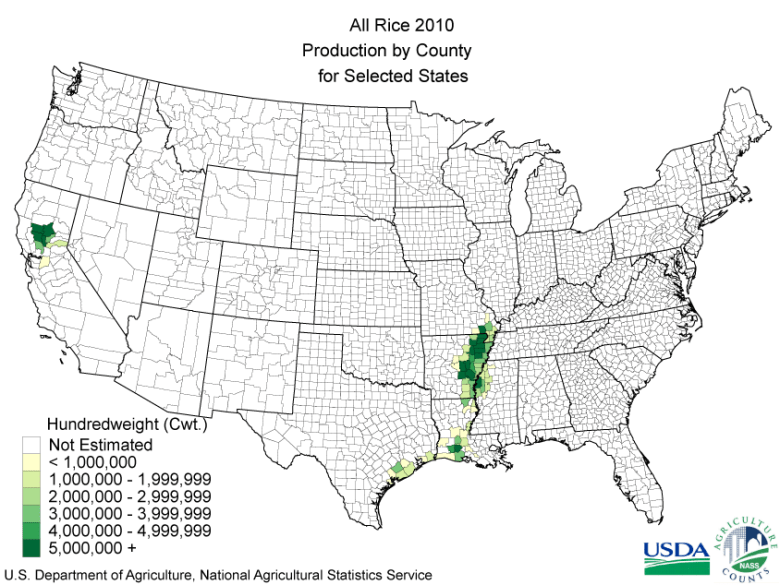

Across the South, the rise of advanced machinery and new technological innovations allowed for rice production to boom in Arkansas, Louisiana and Texas. Between 1890 and 1900, Louisiana and Texas produced almost 75 percent of the nation’s rice.

Simultaneously, westward, across the nation rice traveled from China to California. Initially, the grain was consumed by the population of roughly 40,000 Chinese immigrant laborers. In 1912, commercial rice production began in California, in Butte County’s town of Richvale.

Today, California is the second largest rice-producing state behind Arkansas. According to the University of California, Davis’ Agriculture News, about half of the state’s rice production, $900 million in production value, is exported. Most of the rice produced in California is medium-grain Japonica, which is used primarily in Asian and Mediterranean dishes such as sushi, paella and risotto. Long-grain rice such as basmati and jasmine rice are typically produced in other states such as Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana.

The history of rice reveals a complex past, evidenced by practices of trade, colonization, immigration and technological advancement. Throughout this series, Black Voice News will document how the history of rice manifested through accounts of visual and oral history, and stories of the grain and its importance to various communities through recipes and art.

This project was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library.

Still I Rice!

Part 1: Origins: The History of Rice in American Culture

Part 2: A Visual Archive: Rice’s History in African American Culture

Part 3: Un-Gumbo

Part 4: Traditions and Core Memories: Stories through Rice

Part 5: Middle Passage into the Future

Part 6: A Tale of Two Rices

Part 7: Sitting Pretty