Last Updated on December 22, 2023 by BVN

Article summary:

The O’Day Short Family Unity Garden was established at Randall Pepper Elementary School in Fontana, CA, to commemorate the lives of O’Day Short and his family who were murdered by white racist extremists in 1946. The family was killed when their home was bombed by angry white people who used housing restrictions and restrictive covenants to keep Blacks and other minorities out of white neighborhoods. The incident is now viewed as an opportunity for dialogue about unity, growth, and reconciliation. The garden was inspired by Dr. Daniel Walker, who attended Randall Pepper Elementary School.

S. E. Williams

It was the mid-1940’s when white racist extremists terrorized and murdered a young Black family with a vitriol and animosity that rivaled any of the worst race-based atrocities experienced by Blacks in the depths of Dixie. But, the incident did not occur in the deep south, this quadruple homicide happened right here in the inland region in the city of Fontana when the family dared to move into a white’s only neighborhood.

When President Franklin Roosevelt passed the New Deal in 1933, the nation faced a housing shortage. According to Richard Rothstein, author of “The Color of Law”, this deal set the stage for a federally sanctioned program that was explicitly designed to not only increase the nation’s housing stock, but also to intentionally segregate it. In essence, according to Rothstein, and as noted by NPR, the housing programs that flowed from the New Deal were nothing short of a “state-sponsored system of segregation.” Racists in America leveraged the concept of housing segregation to the extreme using restrictive covenants to work their will.

It would be 15 years (1948) before the U.S. Supreme Court, in the case of Shelly v Kraemer, determined that the government could not enforce restrictive covenants and prohibitions placed on houses, a process that undergirded redlining and prevented Blacks and other minorities from buying homes and living in communities of their choice.

Before the high court’s decision, the housing restrictions– including covenants and prohibitions–were perceived as the easiest way to keep Blacks and other minorities out of white neighborhoods. When that failed, however, white homeowners and other community members often took extreme measures to ensure their neighborhoods remained all white. These measures–more often than not–involved violence.

This was the case in 1946, during the peak of redlining and two years before the Supreme Court ruling, a time when racists took extreme measures in the city of Fontana that O’Day Short crossed the color line and bought a home for his family in Fontana. As a Black man during a tumultuous time, his realization of the American Dream came at an unreasonable and extremely high price–it cost him his life and the lives of his wife and two young children.

After being threatened by the local sheriff, Short was not deterred and moved his family into their new home. Sadly within weeks of settling in, the family was killed when their home was bombed. Short’s wife and two young children died immediately but Short remained alive for about a month before he ultimately made his transition according to the Color Lines in San Bernardino project.

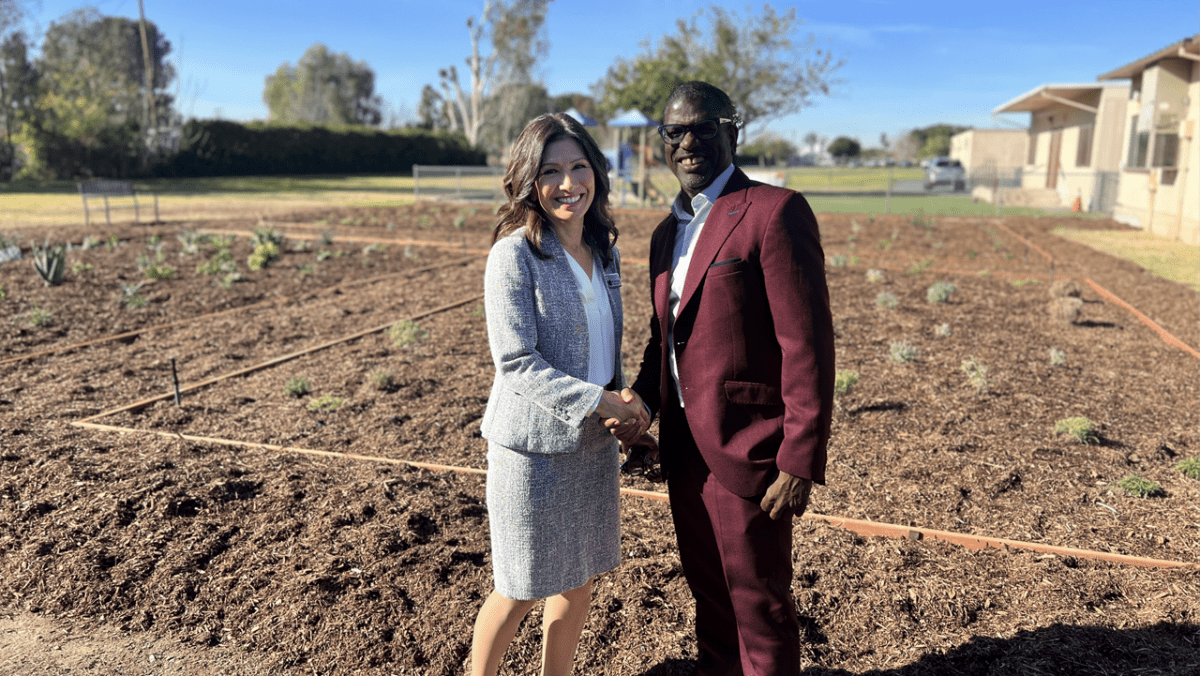

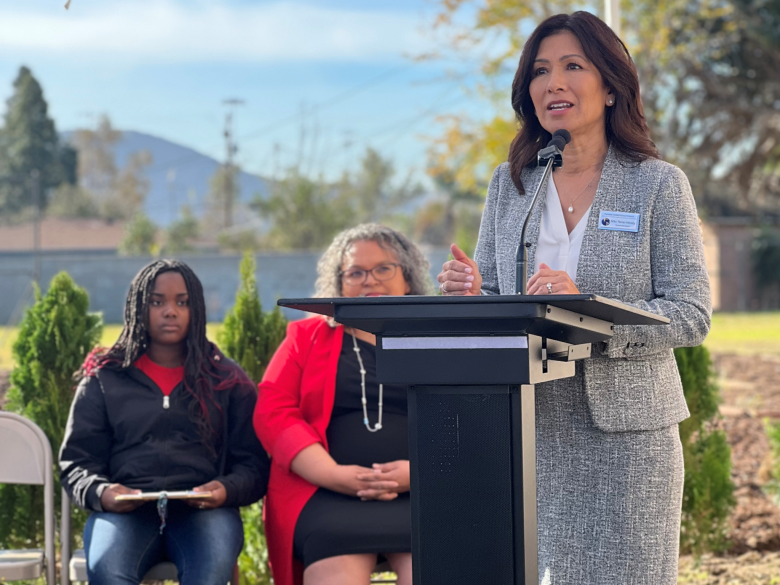

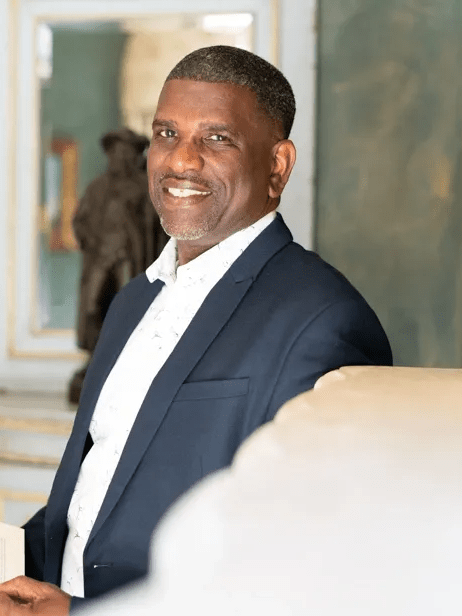

Dr. Daniel Walker, Board Chair/Arts Initiative Director of the Blu Educational Foundation was the inspiration behind the push to establish the O’Day Short Family Unity Garden to commemorate the lives of O’Day, Helen, Barry and Carol Ann Short at the Randall Pepper Elementary School.

In an exclusive exchange with Black Voice News, Walker shared what moved him to champion this initiative. “The fact that I attended [Randall Pepper Elementary School] and experienced some of the most hurtful things young people can do to one another was already a point of pain and anger for me,” he began when asked to share about his involvement with the O’Day Short Family Unity Garden and why he felt it was so important for the community to have this memorial.

Years later, when Walker attended college at San Diego State University he introduced himself as being from Fontana in a class taught by California’s current Secretary of State, Dr. Shirley Weber. “She asked me if I knew the story of O’Day Short and his family.”

Walker said when he told Weber he knew nothing about the incident, she sent him to the library to research the story. “When I read more, I knew that the spirits that were working so hard against my existence in that school at that time were the same spirits that killed O’Day, Helen, Carol Ann and Barry Short.”

Walker explained how he couldn’t figure out which part of the tragedy riled him the most. “Was it the murder of an entire family for simply wanting to live the American Dream? Was it that Barry and Carol Ann were elementary school-aged children and that the Fontana Unified School District bought the land and put an elementary school right on top of their ashes? No, I know what it was. . . It was the almost 80 year silence and erasure of their lives,” he declared.

For 30 years Walker said he’s been telling the O’Day Short family story wherever he went, especially in education settings given that the district still allowed the KKK to use its school facilities for their meetings as late as the mid 1980s.

In 2016, a group of concerned residents including Eduardo Gil, Ipyani Lockhart, and the descendants of Jesse Turner, a Fontana organizing legend, began pushing the school district to acknowledge the crime committed there, to memorialize the family, and to begin a process of using this incident as an opportunity for dialogue and deep programming about unity, growth, and reconciliation, according to Walker.

“In 2020, during COVID, I was the orientation day speaker for all of the employees in the district via zoom and I highlighted the story. When many in the district heard it for the first time.” Walker noted how they did their research, began to take action. It was these actions, from the ground up, that resulted in the Unity Garden.

“For me, to speak at this dedication exorcized 40+ years of hurt, and replaced it with deep hope for my community, the nation, and the world,” Walker concluded.

Despite the Supreme Court ruling in 1948, racists and restrictive practices in housing persists, though they often rest on more subtle means like mortgage denials for example.

To learn more about redlining in the Inland Empire (including additional information regarding O’Day Short) explore the Black Voice News three part series titled The Thick Red Line: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire.