Last Updated on November 27, 2023 by BVN

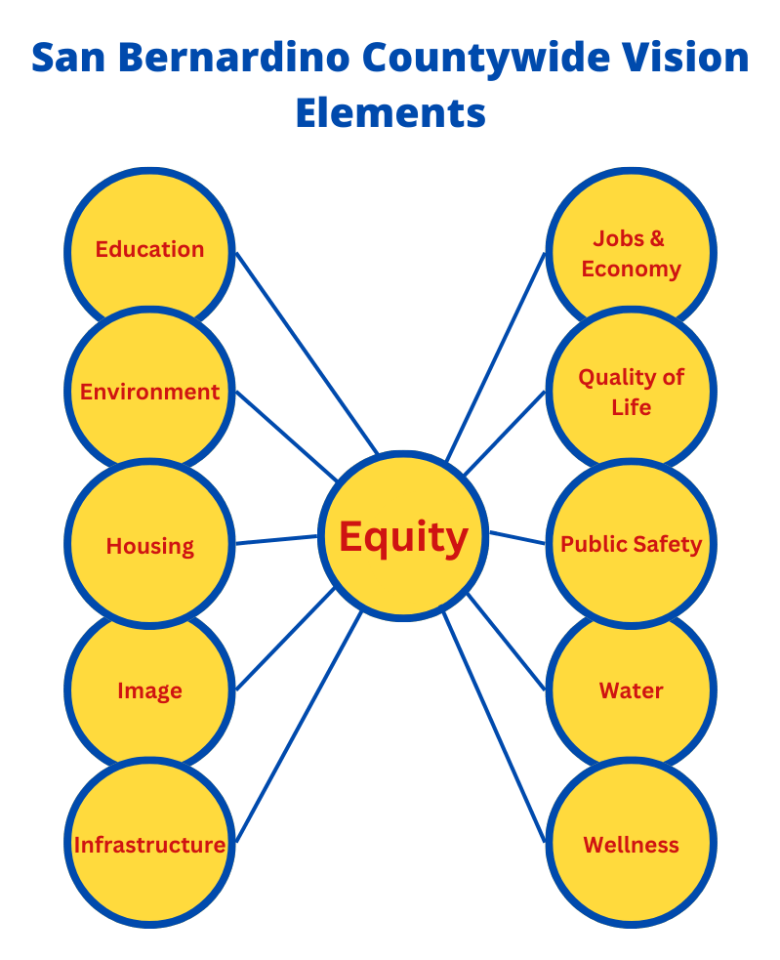

San Bernardino County passed the first resolution in the state of CA declaring racism a public health crisis and pledged to take action to address it. The county added Equity as the 11th element to its Countywide Vision and created an equity element committee that is integrated into the county’s other 10 element groups to provide an equity lens across their decision-making processes. Meanwhile, Riverside County’s declaration pledged to increase diversity across the county’s workforce, address the social determinants of health, and support equitable policies countywide. There were also municipalities around the state including the City of Fontana and Yolo County that did not include any actions in their resolutions to address racism as a public health crisis, leaving many to wonder if such declarations were purely symbolic.

Breanna Reeves

Editor’s Note: Mapping Black California (MBC), created by Black Voice News, is a project that aims to collect and publish data to help eliminate systemic inequalities. One of MBC’s projects is an interactive map of official declarations by local and regional government officials establishing racism as a public health crisis. The aim of this is to provide a resource for tracking and holding these entities accountable for following through on declarations and statements. For this series, Black Voice News partnered with The Starling Lab for Data Integrity, a research lab anchored at Stanford University’s School of Engineering and the University of Southern California’s Shoah Foundation. The Lab prototypes authentication technologies and principles to bring journalists, legal experts and archivists into the emerging world of the decentralized web. These tools underscore the importance of accuracy and serve to combat mis- and disinformation. Decentralized tools can create a technological chain that identifies the history, or “provenance,” of a piece of digital content, serving to reduce information uncertainty and bolster trust in digital content. To learn more about these technologies, click here.

On March 3, 1991, before the age of social media, Los Angeles plumber George Holliday recorded an 89-second video of Los Angeles Police Department officers beating a Black man, 25-year-old Rodney King.

Severely beaten, King was handcuffed, and later taken to the hospital with a fractured leg, bruises and other injuries. Holliday sold the footage to KTLA which broadcast the video before selling it to CNN.

It’s been more than 30 years since this incident of police brutality ignited an uprising in LA after a jury acquitted the four officers involved in the incident.

Today, there’s an entire generation who probably never heard of King or the LA Riots. Instead, they know the story of another Black man, 46-year-old George Floyd, who was killed by Derek Chauvin, a white Minneapolis police officer, who kneeled on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds on May 25, 2020.

In an episode of history repeating itself, this incident of police brutality was captured on camera by then 17-year-old Darnella Frazier. Similar to King’s violent encounter with police, the video of Floyd’s murder quickly went viral across the world, sparking a wave of rage among Black communities and rekindling the flame of anger for older generations who witnessed King’s beating.

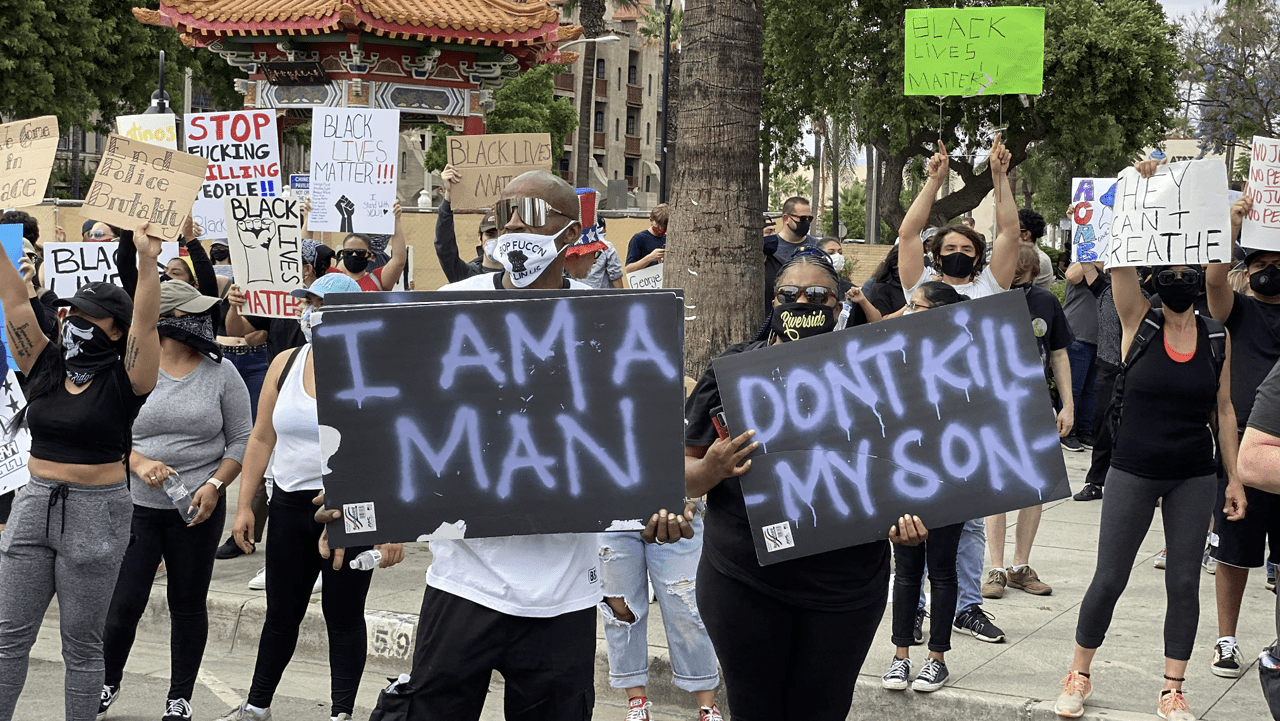

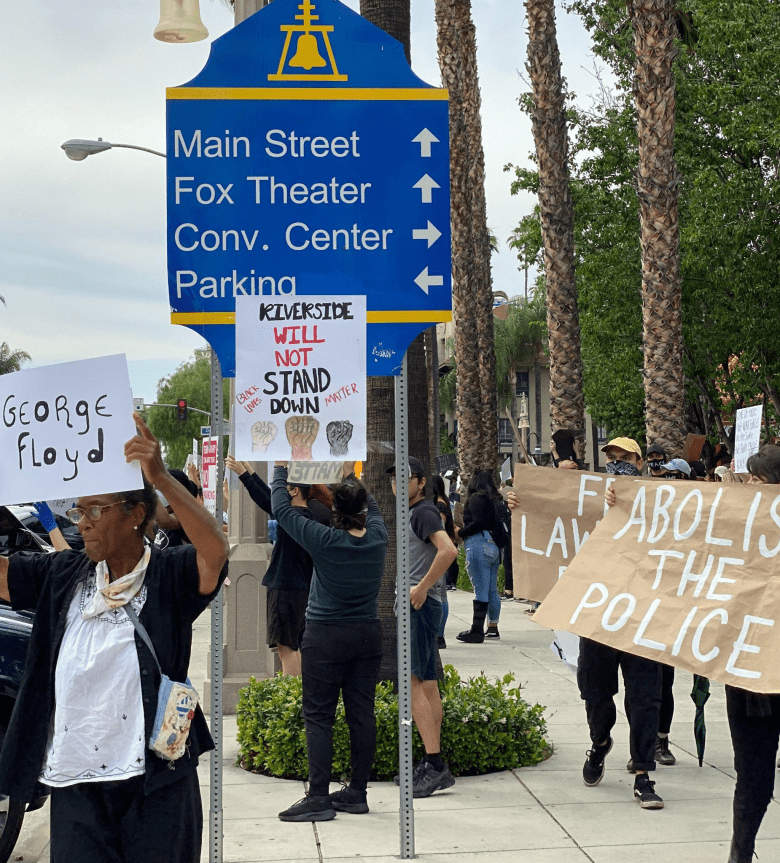

What followed Floyd’s murder was a summer of unwavering protests against police brutality, anti-Black sentiments, racial violence and calls for justice for Floyd as well as for the dozens of Black individuals who had been killed as a direct result of racism.

The culmination of centuries of racism, the global COVID-19 pandemic that disproportionately impacted Black communities and communities of color, and Floyd’s murder led to demands for change in the U.S. It also directly contributed to an unprecedented chain reaction: counties and local governments declared that racism was a public health crisis.

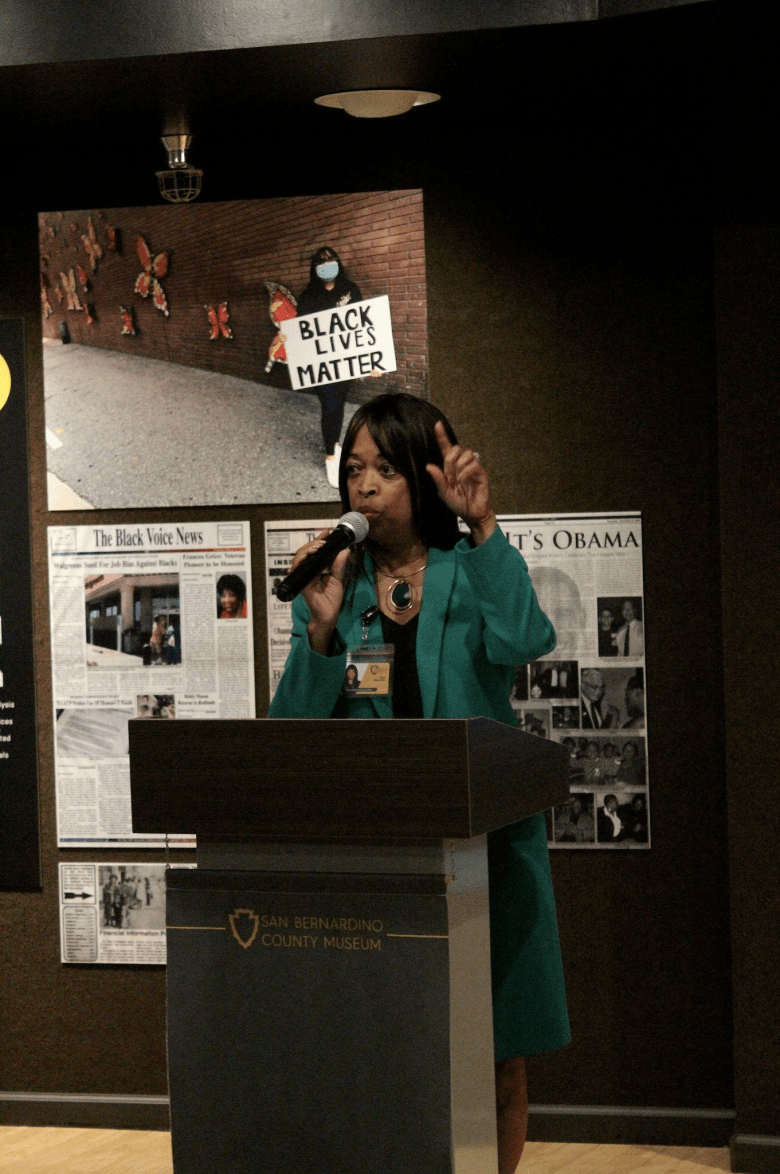

Like most of the world, Diana Alexander, San Bernardino County assistant executive officer, witnessed Floyd become a victim of police brutality. Alexander explained that people in San Bernardino acted like they were far removed from what happened in Minneapolis, but they weren’t.

“I had gone to our [chief executive officer] at the time and said, ‘We need to do something. We need to realize that even though that’s way over there, we got stuff right here,’” she recalled.

“We ought to be able to do something to show our county, our community and our country — and whoever else — that we recognize [the] need. We don’t [have] to wait for a George Floyd or something like that to come up.”

COVID-19 Pandemic Impacts Momentum of Equity Resolution

On June 23, 2020, the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors passed the first resolution in the state declaring racism a public health crisis and pledged to take action to address it.

The Starling Lab for Data Integrity used webrecorder technology to capture and store San Bernardino County’s declaration, along with hundreds of other declarations and associated documents to establish a digital ledger of these promises and pledges.

In an age of mis- and dis-information, it can be hard for the public to trust what they see on social media or across some news websites. With growing use of artificial intelligence, the spread of fake information has also increased, according to Lindsay Walker, product lead at The Starling Lab for Data Integrity.

“We’re trying to create even better tools and more comprehensive tools, so that we can have as much reliable information out there as possible,” Walker said.

Among the county’s actions as listed in their resolution is the commitment to “actively participate in the dismantling of racism by” establishing equity as an additional element as part of San Bernardino’s Countywide Vision and creating an equity element committee. The Board adopted a Countywide Vision in 2011, which outlines the county’s perception of the future.

Once the board of supervisors approved the resolution, they assigned it to the county administrative office to oversee. The county’s Chief Executive Officer Leonard X. Hernandez requested Alexander begin taking steps to lay the foundation for making the resolution actionable.

At the community’s request and with board approval, the county officially added Equity as the 11th element to their Countywide Vision.

The other elements include public safety, education, jobs & economy and wellness, among others. Members of the Equity Element Group (EEG) have been divided and integrated into the other 10 element groups to provide an equity lens across those decision-making processes.

County officials decided to reach out to roughly 16 Black-led organizations throughout the county and ask leaders within them if they were interested in participating in the group.

The first year was spent acclimating group members to the Countywide Vision. Alexander and her team brought individuals from the other element groups and new members of the equity group together to examine the different visions through an equity lens. A lot of time was spent teaching members of the equity group about how the county runs, what role everyone plays and what resources the county has available.

“After we’d done that for a while, one of the things that I really wanted to do was to bring in a consultant, because I recognize that just because I’m Black, [that] doesn’t make me an expert,” Alexander pointed out.

In the midst of this planning, the COVID-19 pandemic was ongoing. During the holiday season of 2020, the county experienced sharp increases in COVID-19 cases which continued into 2021. According to the county’s data dashboard, there were more than 4,000 new cases per day from Dec. 14, 2020 through Jan. 5, 2021.

San Bernardino County’s Community Inidcator’s Report shows COVID-19 case rates in the county “outpaced” state and national rates as of January 2021.

“It was difficult to focus,” Alexander admitted.

Like most plans during the pandemic, the declaration fell to the wayside as COVID-19 became a greater priority. Counties across the state shut down and residents were ordered to shelter in place. At the time, Alexander was juggling several other jobs.

The resolution dropped lower on the county’s list of priorities.

“It did take a hit to the momentum that we had as far as focusing on equity because we were so focused on COVID-19 for the rest of 2020, and 2021,” Alexander explained.

San Bernardino County’s Progress and Challenges

As the COVID-19 pandemic slowed following the release of vaccines, establishing the EEG again became a top priority. The county hired Equity & Results, a consulting firm who utilizes anti-racist principles “with a results-based framework.”

Under the guidance of Anti-Racist Impact Facilitators Theodore B. Miller and Hyma Menath, the EEG has been working to establish goals and how to move forward to make an impact in the county.

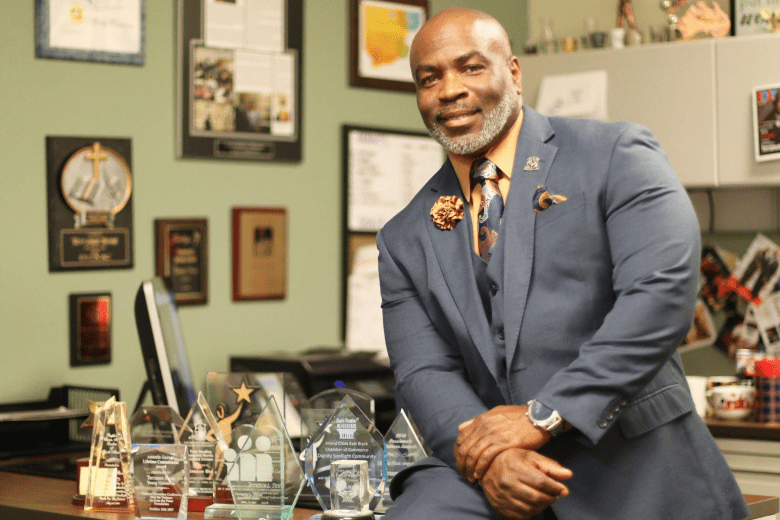

“When you think of systematic racism, there’s a lot of different arms — tentacles really — that are involved in that,” said Terrance Stone, founder and CEO of Young Visionaries Youth Leadership Academy. Stone is one of the 16 members of the EEG, and is also part of the Education element group and the Jobs & Opportunities element group.

On June 22, 2023 — three years after declaring racism a public health crisis – San Bernardino County and the EEG hosted a community address to give residents an update about the progress of the resolution.

During the community address, members of the element group such as Pastor Samuel Casey of Congregations Organized for Prophetic Engagement (COPE) and Stone addressed residents and stakeholders about ongoing EEG plans.

“People say, ‘Well, it’s been three years, what have you done?’” Stone said. “I’m like, ‘We’re trying to break down a system that has been in effect for probably 100 years or so.’ We’re dealing with that. We have to deal with it systematically.”

While people in the community may be concerned with individual issues such as getting contracts with the county and diversifying the county’s workforce, the EEG is taking a systematic and structural approach such as examining practices and policies that will support Black and brown communities as a whole.

“We have to be willing to be bold and courageous to do what we’ve never done if we want to see what we’ve never seen,” Casey emphasized.

As the county works to adopt an equity lens that will impact the greater community, they are also taking steps to examine their internal structure. They recently launched an inaugural Racial Equity Cohort in which 46 members from eight departments are participating. These individuals will explore how equity and diversity are defined, and what equitable policies look like in San Bernardino County.

The County has spent three years strategizing and planning, and is now working to execute plans and consider proposals made by the EEG, but the group itself has been met with challenges.

“I think we underestimated the time and effort that it really would take to actually move a system because that’s what we’re really dealing with,” Stone admitted. “But if we can change the system, so that the system doesn’t benefit the racist, but benefits the people — that’s what we’re working on now.”

With the recent changes in leadership in San Bernardino County, Stone said it will take time for these element groups to establish meetings as new leadership prioritizes other duties.

On Sept. 12, the San Bernardino County Board of Supervisors appointed Luther Snoke as the county’s new CEO who replaced former CEO Leonard X. Hernandez. Previously, Snoke served as the chief operating officer (COO) where he “worked closely with county executive leadership and department heads to develop the Countywide Vision,” according to a county statement.

Since declaring racism as a public health crisis and the subsequent development of EEG, members of the group often get one question from community members: “What are you guys doing?”

“The simple answer to that is that we’re meeting, we’re trying to figure out how to collaborate effectively and work with the whole county of San Bernardino with 16 people [who are] representing all the Black people in the county of San Bernardino,” Stone said. “We’ve been meeting and strategizing.”

As the group surveys different communities across the county, they are learning about the difference in needs of Black residents who reside in Chino Hills or Rancho Cucamonga compared to those who live in the cities of San Bernardino and Victorville.

Across the county, Alexander has learned that there are a lot of Black business owners and community members who are interested in job and economic growth. Oftentimes, business leaders in the community lack the capacity or have no training on how to submit adequate requests for proposals (RFP) for open calls that will allow them to secure contracts with the county.

Alexander is optimistic and proud of what the county has accomplished, not only with their declaration, but with the plans they have coming down the pipeline including hiring a communications consultant and developing capacity building training for small businesses.

“It’s like, you plant the seed and you water it and it takes a while to grow,” Alexander described. “There’s been a lot of stuff behind the scenes that maybe people aren’t aware of, but now it’s starting to grow and it’s going to start producing fruit.”

Riverside County’s Commitment to Equity and Health

On June 30, 2020, the Riverside City Council declared racism a public health crisis, and called on the county to join them in doing so. On Aug. 4, 2020, Riverside County’s Board of Supervisors adopted a similar resolution.

The city’s resolution emphasized its commitment to promote equity by requiring equity training for city staff, to generate periodic progress reports on city goals and to support equitable policies. The city’s resolution offered relatively vague pledges that provided no specific details about funding, explicit goals or timeframes for when these pledges would begin. The declaration made no mention of police reform, but does employ an independent review of complaints against riverside police under the city’s Community Police Review Commission.

Among the county’s actions as listed in their resolution is the commitment to “actively participate in the dismantling of racism by” establishing equity as an additional element as part of San Bernardino’s Countywide Vision and creating an equity element committee. The Board adopted a Countywide Vision in 2011, which outlines the county’s perception of the future.

However, by August, the city hit the ground running as then Mayor Rusty Bailey and his team developed the Riverside Anti-Racist Vision. The vision includes a series of anti-racist principles and practices that promote racial equity such as having “courageous conversations,” using evidence-based analysis and supporting anti-racist actions.

In line with the city’s declaration, Riverside County pledged to increase diversity across the county workforce, address the social determinants of health and support the creation of a Riverside County task force to address implicit bias as it impacts health and wellness. In 2020, the county engaged the community in a series of listening sessions to understand residents’ lived experiences with racism and social injustice.

As part of their commitment to promoting equity across the county, both within county departments and in the community, Riverside County developed a Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Access (DEIA) Task Force. In October 2022, the county hired Barry E. Knight as the DEIA Officer. The task force has outlined upcoming plans as they continue to carry out the pledges currently in process such as making implicit bias training available to all county employees by Spring 2024 and publishing a county wide equity plan in 2024.

Several departments in the county are working to implement equitable policies and practices as a result of the declaration including Riverside County Probation which assigned the Justice System Change Initiative division to examine internal processes and utilize data to make recommendations for improvement.

To further promote health equity, Riverside University Health System developed the health equity team to address the social determinants of health and barriers to health as it impacts communities of color.

“You can’t move forward on something until you recognize there’s an issue. It’s now countywide that we’re working together on challenges, to be more inclusive, to be more equitable, as a county,” said District 5 Supervisor Karen Spiegel.

Some declarations more symbolic than substantive

As dozens of local governments and counties across California passed resolutions to address racism as a public health crisis in the last three years, many of them committed to taking tangible actions that would transform their communities, their cities and their policies.

For other cities and counties, making the declaration was a symbolic act that didn’t include any commitments, changes or offer anything to the community other than a statement.

According to Mapping Black California’s (MBC) dashboard, Yolo County and the City of Fontana did not include any actions in their resolutions. While Fontana’s proclamation recognized that COVID-19 exacerbated existing racial inequity and declared racism a public health crisis, the city offered no solutions or statements of change.

“Based upon this Proclamation, the City of Fontana initiates and supports efforts that work toward promoting a fair and just society; ending racial and social disparities; eliminating barriers that reduce opportunities for residents of color; and meaningfully advancing justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion,” the proclamation stated.

In the absence of specific actions listed in the declaration, the mayor’s office has recognized that promises without action are fruitless. Accordingly, the city has expanded on existing programs such as Fontana Mayor’s Education Coalition, which develops career pathway initiatives for students, and the Healthy Fontana Initiative, a program that promotes a healthy lifestyle in communities.

“We are committed to fostering a city where everyone, regardless of their background, can lead a healthy, fulfilling life. Fontana is leading the way, showing that change is not just a possibility but a reality,” said Mayor Acquanetta Warren.

One concrete step Fontana took was addressing mental health crisis calls in the wake of George Floyd’s murder by launching the Police Chief’s Roundtable to foster “open discussions and enhance relationships throughout the community.”

The development of the Crisis Outreach and Support Team (C.O.A.S.T.) was a result of the roundtable. The team is composed of a Fontana Police Department officer, a social worker from the San Bernardino County Department of Behavioral Health and a firefighter from the San Bernardino County Fire Department.

Similarly, Yolo County offered no details on specific commitments or actions they would take to address racism as a public health crisis.

As some of these vague declarations fade into the background, there’s no way to hold these city and county officials accountable because they didn’t make any concrete commitments.

Without offering any specific pledges, Yolo County’s declaration stated, “The Board of Supervisors of Yolo County has committed to a course of action that recognizes and addresses racism and its attendant inequities in a manner that will endeavor to erase the pernicious and destructive damage of racism by ensuring meaningful progress in improving.”

Although not stated in the declaration, Yolo County created the Inclusions and Diversity Working Group in 2019. The group includes staff from all county departments who are tasked with examining current county practices and making recommendations to those practices so they benefit staff and community interests.

Part of the reason MBC researchers Alex Reed and Candice Mays developed a dashboard with a collection of all declarations made across California is to help communities stay informed about what their local officials said they would — or wouldn’t — do to address racism as a public health crisis.

“By having this collection of declarations, not only is the public able to access these declarations in perpetuity, to see what promises are made, they’re also able to assess whether or not where they live [declared] anything,” Mays explained.

The end goal of the dashboard is to illustrate that racism is still very real and impacts people in their daily lives, Reed emphasized.

“When you can break those numbers down, and you can present them plainly in front of people, it’s so much harder to refute. It’s so much harder to say [racism is] all in your head,” said Reed.

Public Safety Reform Absent in Resolutions Declaring Racism a Health Crisis

When jurisdictions across the country declared racism a public health crisis after witnessing ongoing fatal instances of police brutality against Black people and witnessing the disparate way COVID-19 impacted Black and brown communities, many believed this to be a turning point.

With these one-of-a-kind declarations, it seemed as if government leaders and communities were on the same page about the pervasive nature of racism and came to a consensus that institutions must be transformed.

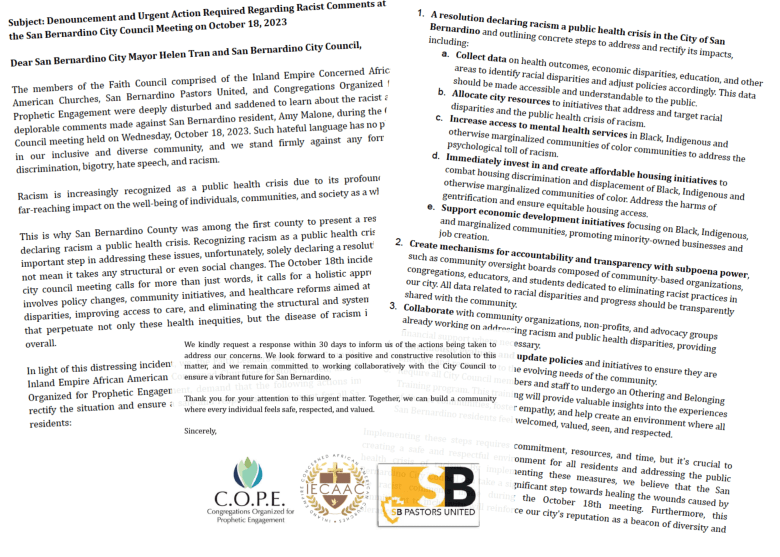

During a San Bernardino City Council meeting on Oct. 18, 2023, Amy Malone was verbally attacked by persons who used racist and hateful language through the Zoom audio feature, during the public comment section. Following the incident, community members and leaders called for more action — more than an apology by city officials — to be taken in response.

“The racist comments made during the October 18, 2023 City Council meeting by individuals connected remotely through Zoom were offensive and unacceptable, and the City of San Bernardino condemns what happened in no uncertain terms,” according to a city statement. “The City apologizes to anyone who heard what was said.”

In a letter addressed to Mayor Helen Tran and the city council, faith leaders in the community demanded tangible action from city officials, including passing a resolution declaring racism a public health crisis in the city. They also requested that the city take concrete steps such as collecting data, allocating resources, increasing access to mental health services and investing in affordable housing.

“Recognizing racism as a public health crisis is an important step in addressing these issues, unfortunately, solely declaring a resolution does not mean it takes any structural or even social changes,” the letter read. “The October 18th incident at the city council meeting calls for more than just words…”

Despite the intentions of these resolutions, addressing racism at the institutional, economic and social level is a heavier lift than most local governments realized. Transforming these resolutions into reformative actions is a long-term commitment that requires the participation of the community, government leaders, county department heads and community-based organizations.

Notably across many declarations is the absence of reform to public safety and police oversight. According to MBC’s dashboard, less than six jurisdictions included language committing to external/internal reform of police department policies or any public safety considerations.

Considering that violent police actions and flawed police procedures were, in part, the impetus for the declarations, there is a glaring absence of police or public safety reform in a majority of efforts. While some jurisdictions have addressed law enforcement reform like Santa Cruz County’s new Office of the Inspector General, other counties have not. County boards of supervisors have very little oversight of these independently elected sheriffs and how they manage their departments. As such, efforts related to potential reforms are primarily in the sheriffs’ hands.

While declarations recognizing racism as a public health crisis continue to develop and evolve, many believe it is essential that police or public safety be incorporated as an essential part of these efforts. If not, the narratives of King, Floyd and countless others will be replicated as history continues to repeat itself. With this in mind, although the well-intentioned efforts to address the public health crisis of racism will progress, many jurisdictions will fall short of their overarching goal by failing to address one of the key elements that sparked the movement initially — police use of deadly force.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that San Bernardino County’s Racial Equity Cohort chose six members from several departments to participate.

Combating Racism as a Public Health Crisis

Part 1: Holding Leaders Accountable

Part 2: Santa Cruz County’s Inclusive Resolution

Part 3: Oakland Addresses Systemic Racism with Data-driven Approach

Part 4: Riverside and San Bernardino Counties Take Action Against Racism as a Public Health Crisis