Last Updated on June 4, 2024 by BVN

If you are the victim of a hate crime, please contact your local law enforcement agency. For additional information please visit oag.ca.gov/hatecrimes.

Mariah Brown

In the sweltering summer of 1946, a modest community center in San Bernardino buzzed with anticipation. The room was packed, a sea of faces reflecting the area’s rich diversity. On stage, Ignacio Lopez, a fervent advocate for Mexican American rights, prepared to speak. Beside him stood a leader from the local chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). The crowd, a mix of Black and Mexican American residents, had gathered for a joint meeting to address rampant housing discrimination.

Lopez stepped forward, his voice carrying the weight of the moment. He spoke about the shared struggle against injustice and the power of unity. The room responded with enthusiastic applause, reflecting their collective resolve to fight for equal rights.

This alliance marked a turning point in the Inland Empire’s civil rights movement, demonstrating the profound impact of multiracial collaboration. As the meeting continued, stories were shared, strategies were planned, and a unified front was formed. This moment of solidarity echoed through the decades, laying the groundwork for continued activism and reinforcing the region’s enduring commitment to justice.

In the narrative of American civil rights, the Inland Empire in California holds a profound, yet often overlooked chapter. While many associate the movement with spontaneous events in the mid-20th century South, the Inland Empire’s history reveals a deep-rooted and persistent struggle for racial justice that predates these more widely recognized milestones. The region’s legacy of civil rights activism, spanning diverse communities and numerous decades, underscores a continuous fight for equity and justice.

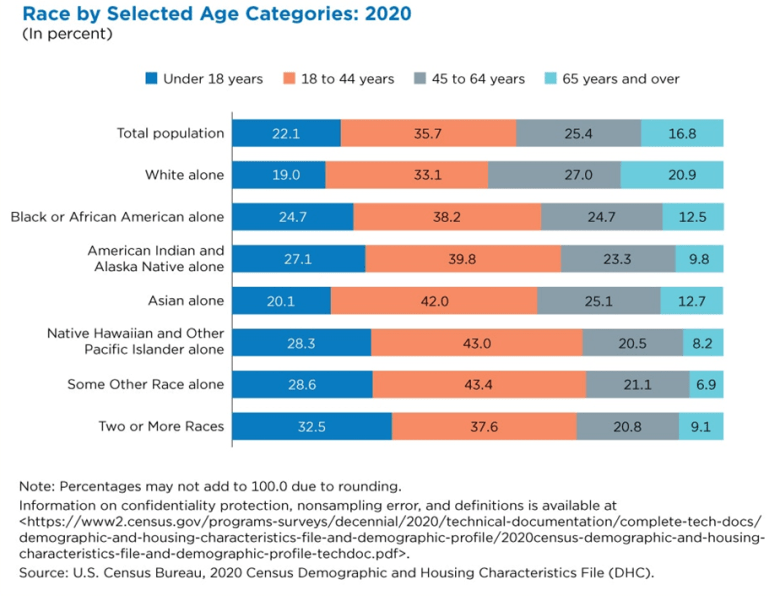

The history of coalition building among races in the Inland Empire underpins continuous efforts for racial equity and the region’s future. Building constructive bridges between groups, while everlasting, may be enhanced by a growing Multiracial population. The 2020 Census showed the Multiracial population has increased exponentially in California and is the youngest of any racial group, with about 32.5% under age 18.

Multifaceted Struggles: Diverse Racial and Ethnic Groups Fighting Injustice

The fight for civil rights in the Inland Empire has deep roots, spanning various racial and ethnic groups who rallied against injustice. As early as 1919, chapters of the NAACP were established in Riverside and San Bernardino. These early activists worked tirelessly to desegregate public spaces, such as the public pool in Riverside, and to protest discriminatory practices in local restaurants, employment, and healthcare facilities.

Mexican workers at the CalPort Cement plant also played a critical role, striving for equal pay when they discovered wage disparities between themselves and their white counterparts. The Harada family, of Japanese descent, challenged racial segregation in housing, setting a precedent for future legal battles. The indigenous people, including the San Manuel Band of Mission Indians of San Bernardino County and the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians of Riverside County, have long fought for civil rights, seeking recognition and protection of their ancestral lands and culture. Among the nine federally recognized Cahuilla tribes, each with its own reservation and tribal council, the Agua Caliente Band established their Tribal Council in 1955, a major milestone in their sovereignty after years of separation, discrimination, and government control.

In the 1960s and 70s, nationwide protests improved relations between Native Americans and the federal government. President Richard Nixon’s 1970 call for tribal self-determination led to the 1975 Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act, allowing San Manuel and all federally recognized tribes to exercise self-governance.

These early efforts reveal that civil rights activism in the Inland Empire was a mosaic of different racial and ethnic groups, each fighting their own battles against injustice, according to Jen Tilton, associate professor, race and ethnic studies, and co-director of Liberal Studies at University of Redlands.

Moments of Multiracial Collaboration

While civil rights organizing often occurred within separate racial or ethnic groups, there were significant moments of collaboration. In the mid-1940s, both Black and Mexican residents on the Westside were actively engaged in civil rights activism. Although their networks largely operated independently, leaders like Lopez, a prominent figure in Mexican American civil rights, worked alongside Black NAACP leaders at conferences to advocate for fair housing and employment.

In the Inland Empire during the first half of the 20th century, housing segregation was deeply rooted, leading to the Eastside of Riverside and the West Side of San Bernardino emerging as densely populated multiracial hubs. Faced with discriminatory practices such as racial covenants, informal agreements among real estate agents and homeowners, and reluctance from lenders, “residents united through coalitional politics and entrepreneurial efforts,” said Catherine Gudis, associate professor at UC Riverside, exploring race, place, and space histories in Southern California.

These moments of collaboration, though sometimes under-documented, were crucial in uniting different communities in their shared fight against discrimination, according to Tilton.

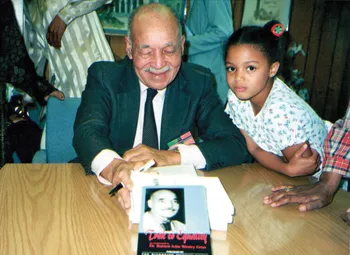

In 1962, Dr. Barnett Grier, a physicist new to the Inland Empire, catalyzed change. By facilitating the sale of a Rialto home to a Black family, he not only broke barriers, but also became the region’s first Black real estate broker. His bold action stirred a storm of protest, leading to a month of demonstrations and vandalism. Despite the turmoil, Grier and his allies remained steadfast, inspiring others to challenge the entrenched racial divide. With legal tactics learned from NAACP chapters in San Bernardino and Los Angeles, residents waged an unwavering fight for representation to push back against the color line.

The 1960s: A High Point of Activism

The 1960s marked a significant era of civil rights activity in the Inland Empire, with local leaders supporting national movements and organizing on the ground. In San Bernardino, activists like Frances Grice, Bonnie Johnson, and Valerie Pope founded the Community League of Mothers, leading school boycotts and protests to demand desegregation and equal education for Black and Mexican students on the Westside.

The NAACP and Congress of Racial Equality intensified their efforts during this period, advocating for fair housing policies and demanding that employers open their doors to Black and Mexican workers, who were often relegated to menial jobs.

The collective efforts of African American and Mexican American women within institutions like the Community Settlement Association in Eastside laid the groundwork for broader community engagement in civil rights activism. This collaborative spirit extended to initiatives such as electing John Sotelo as the first person of color to the Riverside City Council in 1963 and advocating for desegregation within the school board, demonstrating the cohesive approach towards addressing systemic inequalities in the region. Furthermore, local small businesses not only served as economic engines but also played integral roles in fostering leadership development and facilitating discussions on civil rights issues within the community.

These activists were bolstered by the guidance and support of an older generation of leaders, such as Art Townsend, founder of the Precinct Reporter. Townsend utilized the power of the Black press to amplify calls for justice and mobilize the community. “When you look carefully at decades of civil rights activity, you see what scholars call the “long civil rights movement” – and how activists of earlier generations set the stage for later generations of activists,” Tilton said.

The Long Civil Rights Movement: Generations of Struggle

The civil rights movement in the Inland Empire is a testament to what scholars refer to as the “long civil rights movement.” This concept recognizes the continuous and evolving nature of the struggle for racial justice, with each generation building on the victories and lessons of its predecessors. Over the decades, activists achieved numerous concrete victories, such as securing the employment of Jimmy Jews, the first Black firefighter in the area, and ensuring that school districts supported students’ rights to organize Black Student Unions (BSU) and Movimiento Estudiantil Chicano de Aztlán (MEChA) chapters.

However, the fight for racial justice has remained a persistent need. Each new generation of activists in the Inland Empire finds itself defending or extending the gains made by those who came before them. This enduring struggle highlights the region’s commitment to justice and the continuous effort required to achieve and maintain equality, according to Tilton. “Wherever there is injustice, you find everyday people standing up for civil rights and racial justice,” she said.

The pursuit of self-determination has remained a cornerstone of African American and multicultural political activism, reflecting an enduring commitment to collective empowerment and equitable solutions to systemic injustices.

Examining the lessons gleaned from self-determining movements reinforces the notion that progress often requires forging new paths amidst uncertainty, said Marc Robinson, Assistant Professor at California State University at San Bernardino. “We may not have all the answers, and the path forward may be unclear, but we should continue the struggle and believe that we are the leaders we are waiting for,” he said.

This resource is supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library in partnership with the California Department of Social Services and the California Commission on Asian and Pacific Islander American Affairs as part of the Stop the Hate program. To report a hate incident or hate crime and get support, go to CA vs Hate.