Last Updated on December 4, 2023 by BVN

The American Dream

What does the term The American Dream really mean? The meaning of the phrase has changed over time, always encapsulating the idea of success. It started out as simply “a dream of equality, justice, and democracy” for all Americas and has evolved to what is more commonly known today, as a dream of wealth and prosperity.

Either way the coin is flipped, Blacks and other minority groups as a whole in America have run into difficulty attaining this dream because of racist and discriminatory practices. One of the main resources toward gaining economic success and sustaining generational growth is the right to homeownership. However, the history of redlining prohibited certain American families from achieving this dream.

Redlining

The idea of redlining originated during the Great Depression of the 1930’s when government-insured mortgage loans were created to help provide a way for Americans to own homes and begin to dig out of the economic crisis.

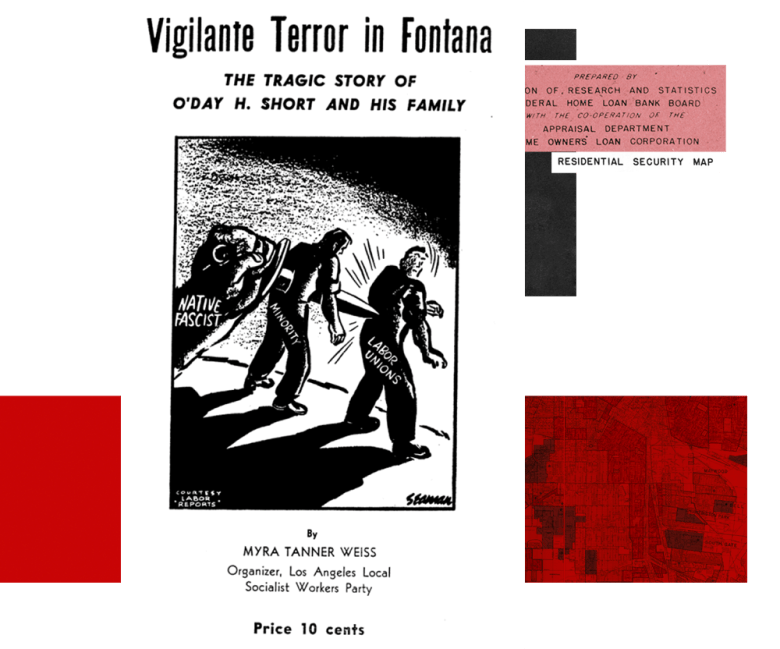

The Homeowners Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps to indicate which neighborhoods would qualify for such loans. Certain areas of the maps were separated with red lines around them. The areas drawn in red were considered unworthy of and risky to inclusion in the new homeownership program.

Simply put, redlining is the act of denying or limiting financial opportunities to specific groups of people or communities based on their race or ethnicity. On April 11, 1968, after several years of consideration and just seven days after the assassination of the African American Civil Rights leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., President Lyndon Johnson signed the Fair Housing Act. This act would make discriminatory practices within housing and “residential real estate-related transactions,” illegal.

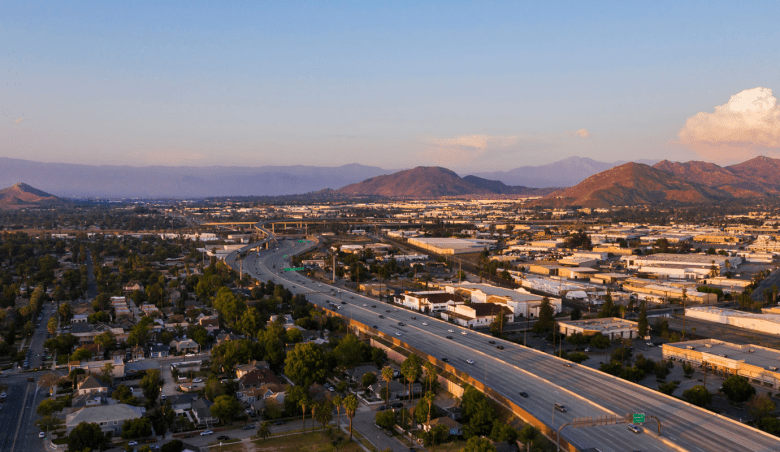

The Inland Empire and Redlining

Located around forty miles east of Los Angeles, California, is the region of the Inland Empire (IE), encompassing two counties known as Riverside and San Bernardino. From the 1920s through the 1960’s until the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968, this Southern California region was no exception in its practices of discrimination and racism, including redlining. However, unlike the larger cities, while the practice was very much at play, redlined maps for the area cannot be found, according to a study by the University of Redlands.

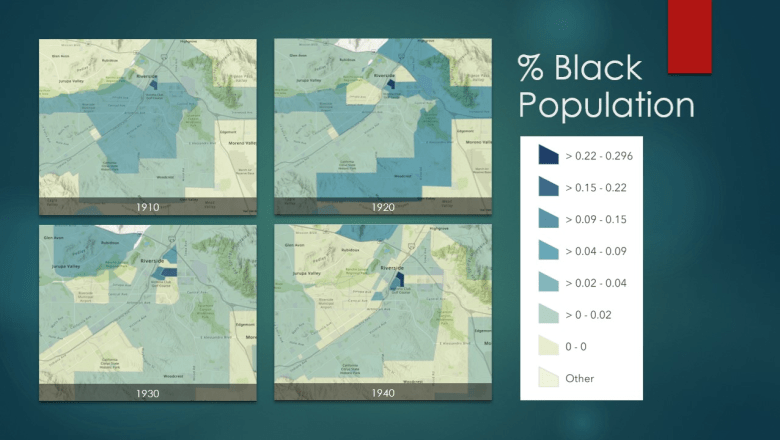

Professor of Race and Ethnic Studies, Jennifer Tilton and her team have built historic census maps that let us see how racial segregation developed in our region. They utilized census data, historical census maps and other local historical sources “to draw enumeration districts (early census geographical units)” for each of four decades (1910 to 1940), in the City of Riverside.

The maps depict how the Black population grew in Riverside through these four decades during the first half of the 20th century, as well as how housing “segregation increased on the Eastside of Riverside.”

Because of its agricultural industry and the prospect of job opportunities during the Second Migration, which began around 1940, many Blacks moved to the IE. In the slide map below, see how Riverside’s Black population grew between 1940 and 1960.

Much like other redlined communities, local newspapers in the area advertised homes with whites only specific language, racial covenants. The language of these covenants was included in deeds and used to discriminate based on race or class. Gentleman agreements were also a part of the process.

Language of a typical covenant might read:

“…hereafter no part of said property or any portion thereof shall be…occupied by any person not of the Caucasian race, it being intended hereby to restrict the use of said property…against occupancy as owners or tenants of any portion of said property for resident or other purposes by people of the Negro or Mongolian race.”

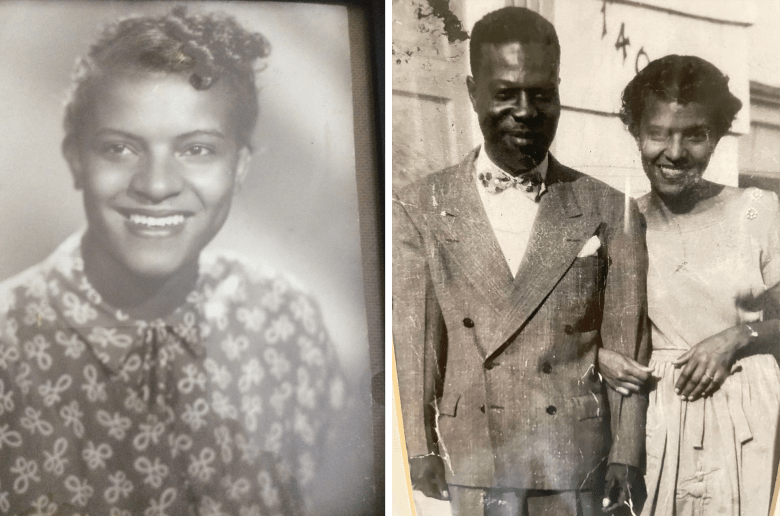

Aside from such written and verbal discrimination, some individuals were met with violence, such as the tragic story of O’day Short and his family, who lost their lives in 1946 because of a violent bombing.

The O’Day Short Family Tragedy

This video tells the tragic story of the O’Day Short family and the alleged story surrounding their loss, on December 16, 1945. (Source: youtube.com)

Overtime, and after the passing of the 1968 Fair Housing Act, racial divides in neighborhoods show more of an leveling out in the Inland Empire, but there are still areas with a higher concentration of minorities, and those areas reflect ones that were redlined during this period.

What about today?

During the era when redlining was still legal, it was a transparent and overt practice. Newspapers advertised properties with language that made it clear that none other than whites would be allowed to rent or own certain properties. Maps were clearly drawn to show where people of color, especially Blacks, could and could not buy properties for ownership.

While the Fair Housing Act of 1968, dissolved the overtness, elements of the practice of housing discrimination still exists today, but with subtlety.

Neighborhoods that were impacted by redlining experienced more poverty, lower educational opportunities, economic disparities, higher crime, and less access to health care. While other racial groups fell into the categories listed as high-risk investments and were redlined, the initial implementation of the practice was specifically targeted toward Blacks and as of 2019, the areas once redlined, are today, more likely to have a higher concentration of Blacks compared to other parts of most cities, according to a report by the Brookings Institute.

So, is redlining in the Inland Empire (and elsewhere) really gone?

The Flight from South Los Angeles to the Inland Empire

In the 1980s and 1990s, a migration took place into the Inland Empire when many were in search of more affordable housing.

Blacks left the “ghettos” of Los Angeles in search of their American Dream—home ownership, no drugs, and nicer schools. The Inland Empire offered such a space promising bigger homes and large yards.

At this time, Moreno Valley, a city on the west side of Riverside, boasted homes with more affordable costs and became the neighborhood that many Blacks leaving Los Angeles’s inner cities, settled in.

While many were enticed by the idea of a neighborhood that was more affordable and suburban, some of those involved in the development of this community were offering a new, risky type of loan that would initially provide the satisfaction of a happy new life, but soon after, prove to send many new homeowners plummeting into insurmountable debt and uncertain futures.

Moreno Valley and Perris

Located in Riverside County sits the city of Moreno Valley and around 11 miles away is the city of Perris. Both cities became more populated by working-class people during the flight from South Los Angeles to the Inland Empire. Moreno Valley was slightly more built up with track homes and Perris was more rural according to Professor of Anthropology and Associate Vice Chancellor for Diversity, Excellence and Equity at the University of California – Riverside, Dr. Yolanda Moses.

The growth of the Black population in Moreno Valley, the Inland Empire’s “blackest city” can be initially credited to the arrival of the March Air Reserve Base. However, in the 1980s, a subtle targeting of the Black communities in Los Angeles began as advertisements were being made to residents to move to Moreno Valley. Later, between the 1990s and 2000s, real estate agents began to give vouchers to residents in Los Angeles.

While some families moved due to these subtle pushes, others moved because of word of mouth from community members, like Candice Mays and her parents, who settled in the area.

Mays was born just months after her family moved from Carson, CA to Moreno Valley in 1986. Her parents were initially homeowners in Carson and decided on a fresh start.

“I’ve…heard stories about Black people who moved to Moreno Valley because they were looking to move inland. They were originally looking in Riverside and builders and real estate agents in Riverside were redirecting them out of Riverside and telling them to buy in Moreno Valley.”

Covenants

Once May’s parents moved their family here, they encouraged at least one of a group of cousins to move to the area. “Growing up, I had a fairly extensive family network in Moreno Valley.” said Mays, Project Director for Black Voice News’ Mapping Black California and Mapping Black initiatives, and resident of Moreno Valley.

Predominantly Hispanic with a 58% (124,204) Latino population in 2019, the Black population in the Moreno Valley was 18.8% (40,111), compared to areas like Riverside which stood at 5.4% and San Bernardino at 15.7 Black residents in the same time period.

While Mays tells the story of a young girl growing up in Moreno Valley, Yolanda Moses has an earlier recollection of the Inland Empire as she recalls her family’s move to Perris, CA.

Moses was a young girl when her father, Henry Moses Jr., moved from Compton, CA to Perris, CA because he had four daughters and did not want them to grow up around gang violence and crime. Moses and her sisters had to adjust to a less exciting life because Perris was so rural “there was nothing going on,” but for her father, it was about safety.

“[I]t was at a time when working-class people could move to places and start over again, or create the kind of lifestyle that they wanted. And because it was more rural, it was kind of open. It didn’t feel as harsh as living under, you know, police surveillance and stuff like that, because there were no real police, it was sheriffs and people like that,” recalls Anthropologist Dr. Yolanda Moses.

According to Moses, many families like her own had similar stories, with some moving into Moreno Valley and others into Perris, however, the newness of both communities meant there were limited jobs, and the people who moved from Los Angeles were still commuting to and fro for work.

While an exit from the inner city to the Inland Empire meant escaping certain types of crime, the lack of social movements at the time did not exempt Moses, or her fellow Black and Latino classmates from a different kind of problem—discrimination in education. With the area being rural, agricultural work had a strong presence, and the assumption was made, based on their race, that they would be attending high school without plans for college and would end up working in the fields.

Moses recounted that her mother, Willie Moses, was heavily involved in the formation of Human Relations Council groups in the Inland Empire, the NAACP local chapter and various churches and church councils, such as the African American AME Church. These groups contributed to getting people of color to vote and eventually led to some running for local office. She credits her mother as a “mover and shaker” and the work she did, and local newspapers, as influential in the area.

While at the time, the move from the inner city to the Inland Empire seemed to present better opportunities for people of color Moses, like Mays states that people of color would still experience real estate steering when moving into the neighborhoods.

Over time, as Blacks continued migrating to the area, a new issue loomed on the horizon that would result in an economic disaster for many–Subprime Loans.

Subprime Loans:

Subprime Loans emerged in the 1980s. This was when lenders bundled mortgages together and sold them as securities to investors, allowing them to gain profit through selling the loans instead of keeping them on their books.

Just a decade later, lenders began offering these loans as mortgage loans for those with lower credit scores. Borrowers would not be required to show as many documents as verification of their income or assets, resulting in higher interest rates and fees than a typical mortgage loan. Yet, it would afford opportunities to buyers who may not otherwise qualify to purchase a new home.

These loans were offered to some minorities moving into the Inland Empire as they left inner cities and the later impact of these loans would cause further economic damage to families. Originally created to be aimed at folks with lower credit scores or income, they were disproportionately offered to Blacks and Latinos, and even provided to some with high FICO scores and good credit.

The story of Billy Ross and his wife when they moved to Fontana, CA, a city in the Inland Empire county of San Bernardino, is an unfortunate example of this issue.

Ross recalls that many were moving from Compton, CA and the surrounding areas where he grew up to the Inland Empire. However, Ross adopted the mindset of his family of keeping roots in the Compton area and originally had not intended to leave. He credits his move as one of practicality, as his wife’s job was in the Inland Empire.

“It’s kind of like two waves for me and we were part of the second wave…the first wave that I saw was…maybe mid to late 90’s…there were a lot of Black people leaving LA…and moving to cities like Moreno Valley,San Bernardino and Rialto.” explained Ross.

Ross and his wife were part of the second wave, which he describes as around the housing cycle that ended in a crash. Many people were moving into the area at this time for opportunity, one that could get individuals more for their money, according to Ross. Although he moved primarily for his wife’s job, he includes them in this wave.

The year is 2006, Ross and his wife, both with great credit, moved into their home after being offered a mortgage loan that was almost too good to be true, with the incentive that they could refinance at any time—it was a subprime loan.

By 2008, their home lost value and they were drowning in payments, while simultaneously being unable to find lenders who would help them refinance their home. This eventually led them to have to take extreme measures to be able to keep their home.

“We had some tough calls to make…do we continue to pay this note, or do we look for some kind of alternative relief and we decided to look for some relief” recalls Ross.

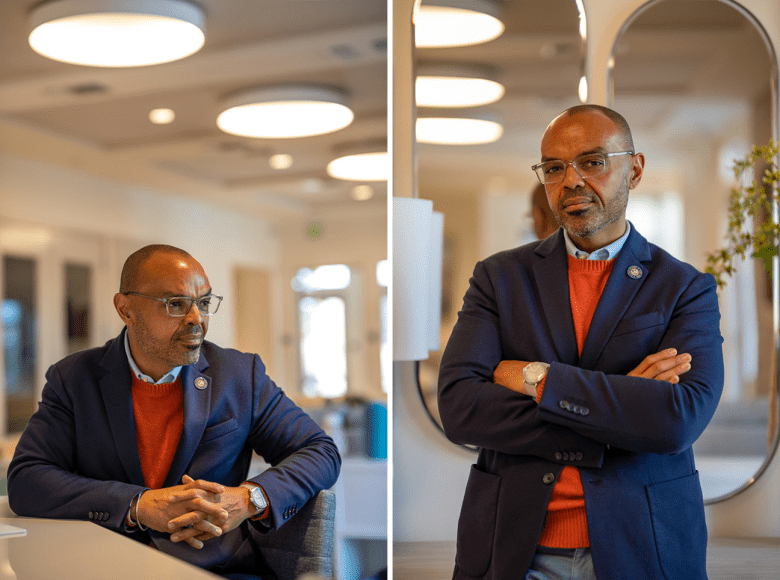

Ross is just one example of the kind of damage that was caused by the impact of loans with poor conditions. Ross, now a Real Estate Broker and the owner of Billy Ross Realtor, believes that he was targeted for this experience because of a narrative he and other Black people bought into. The narrative suggests that the way to build wealth through real estate is to not use one’s own money, but instead to use a loan for leverage. He believes that this strategy may work for investors, but not for families seeking homeownership. Full story of Billy Ross.

Modern Day Redlining

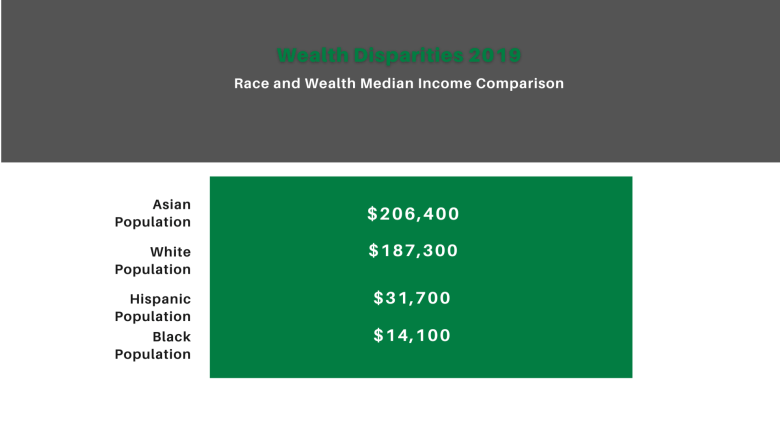

Today, though there have been improvements, studies suggest that the impacts of redlining on Blacks and other minority groups still exist. Wealth inequalities persisted in 2019, according to the latest Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) data released in October 2021.

Wealth is the value of assets owned, minus the liabilities (debts) owed. As described in a previous report on household wealth in 2017, the new U.S. Census Bureau report, and detailed tables on household wealth in 2019 show similarly wide variations across demographic and socioeconomic groups, but also detail generational wealth differences for the first time.

In 2019, Black and Hispanic householders, compared to white and Asian householders had lower median household wealth.

This gap in net worth can easily be tied to the lack of homeownership within the aforementioned groups as many Black and Latino households continue to face issues in their efforts to acquire conventional mortgage loans. Reports indicate they are more likely to be denied conventional loans compared to white applicants who have similar credit scores and credit histories. Such roadblocks to securing home loans only serve to exacerbate the damage already done by the long history of redlining, as homeownership is the primary way most Americans build wealth to pass to future generations.

The difference in homeownership rates between racial groups from the 1960s to now further shows the longer term impact of these discriminatory practices. In the 1960s, before the Fair Housing Act was passed, the rate of Blacks owning homes in California was higher than it is now. In the U.S. at large, Black and white homeownership moved from a 27 point gap to a 30 point gap as of 2017. While the housing gap in California seemed to begin shrinking in the four years prior to the pandemic, factors already in place, such as the previous economic collapse of 2008, which impacted Black and Latino families at a higher rate than whites, are seemingly creating a larger gap post pandemic.

Aside from poor lending practices that are still in existence in the Inland Empire and elsewhere, there are continuing reports and stories being told by residents that suggest Black people are steered into neighborhoods that are predominantly Black.

“I’ve had faculty of color, who have told me that when they first moved here, especially if they come from out of state, there are realtors who first take them to Black neighborhoods…not allowing them to decide…where they want to live,” said Dr. Moses.

Furthermore, while affordability was an upsell in the initial exodus from the inner cities to the Inland Empire, the reverse is now true. Housing costs have more than tripled in the area since the 1990s and early 2000s, with the average home price being around $129,000 in 2000 and is currently around $458,000 according to Federal Reserve Economic Data.

All Transactions House Price Index | Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario CA

(Glide cursor over map to see price by quarter and year.)

Housing costs have more than tripled in the inland region since the 1990s and early 2000s according to the All-Transactions House Price Index for Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA (MSA). (fred.stlouisfed.org)

Redistricting

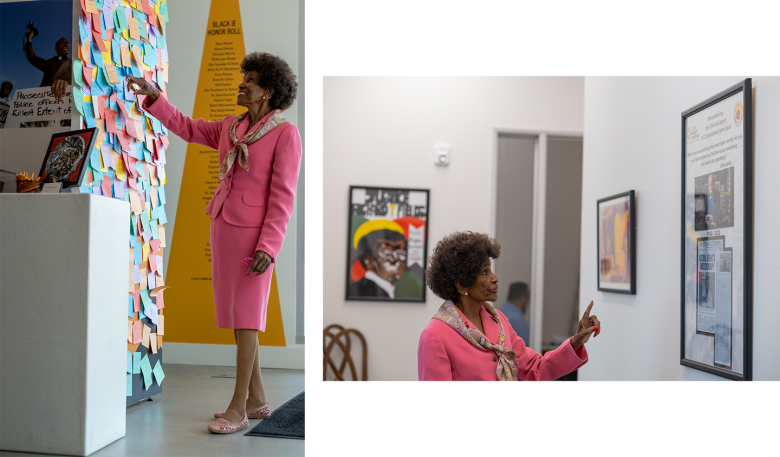

A very current area of concern is the ways in which the practice of redistricting is being implemented in predominantly minority communities. Redistricting is “the process of drawing district lines”. Simply put, this is when the boundaries of an area are changed every 10 years in alignment with the decennial census to balance voting districts based on population shifts at the local, state and federal levels. It also determines federal funding allocations for a number of programs important to underserved communities including Medicaid, Head Start, block grant programs for community mental health services, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, etc. Although this process should not be, it is often political, where areas can be realigned based on some government officials’ ability to see where the most votes are for their own political interests. They then realign the districts in favor of getting a majority vote for themselves and/or their party, according to Rose Mayes, the Executive Director of the Fair Housing Council of Riverside County.

“I’m concerned about that because the low to moderate income people always come out on the end where they don’t get very much support on the national, regional, nor the local level and we’re always having to fight for just the crumbs off the table,” said Mayes.

Based on the work the Fair Housing Council has been involved in, Mayes described that many neighborhoods do not want inclusionary housing in their communities because they don’t want low income families moving into those homes.

As a result, according to Mayes, instead of building this type of housing, the developers negotiate with the city so that low to moderate income housing is eliminated and only higher end housing is included. This leads to inequality in redistricting because people of color with low to moderate income are unable to integrate into other areas in the community due to the high cost of housing.

What or Who is Solving the Problem?

On October 22, 2021, the Justice Department under the Administration of President Joe Biden released an announcement regarding the Redlining Enforcement and Accountability Program (REAP), a new program to combat redlining. The initiative is intended to enforce fair lending practices and investigate instances of redlining. Some of its specifics include: pursuing legal action against lenders, insurers, and other financial institutions for discriminatory practices, supplying resources and training to these institutions, and partnering with relevant community organizations and advocacy groups.

On a local level, the Inland Empire has a few organizations and community groups working to address the issue of modern day redlining and the various ways it impacts the communities in this region.

For example, organizations like the Fair Housing Council of Riverside County, where Rose Mays is the Executive Director, work on a community-based level, providing services to ensure access to individuals and resources related to fair housing discrimination. If you need their assistance they can be reached at (951) 682-6581.

The California Reinvestment Coalition is another organization that focuses on a statewide level to advocate for communities of color and their equal access to financial services. They can be contacted at: (415) 864-3980.

Conclusion

America has a history of discriminatory practices against Blacks and other minorities, but redlining has proven to have severe and lasting impacts yet to be completely dissolved. The practice, in its many forms, continues to prevent predominantly Blacks and Latinos from homeownership. In turn, these communities have been severely disenfranchised of their opportunities for health equity, as was experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic, educational equity, as reflected in academic achievement gaps and lower graduation rates, in addition to the economic limits placed on their ability to generate sustainable, generational wealth.

A special thanks to Professor Jennifer Tilton, University of Redlands and Associate Professor Catherine Gudis, University of California, Riverside. Read and learn more about their work on Black history in the Inland Empire by following these links. Color Lines of San Bernardino, Fighting School Segregation in San Bernardino, Building a Movement on San Bernardino’s Westside, Claiming Our Space, A People’s History of the Inland Empire, and the Bridges That Carried Us Over Project.

This project was supported in whole or in part by funding provided by the State of California, administered by the California State Library.

References

1920s–1948: Racially restrictive covenants. Historical Shift from Explicit to Implicit Policies Affecting Housing Segregation in Eastern Massachussetts. (n.d.). Retrieved February 21, 2023, from https://www.bostonfairhousing.org/timeline/1920s1948-Restrictive-Covenants.html#:~:text=A%20covenant%20is%20a%20legally,future%20buyers%20of%20the%20property.

2020 fair housing trends report – NFHA. (n.d.). Retrieved January 20, 2023, from https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/NFHA-2020-Fair-Housing-Trends-Report.pdf

Agency, C. H. F. (n.d.). Building black wealth. Black Homeownership Initiative: Building Black Wealth | California Housing Finance Agency. https://www.calhfa.ca.gov/community/buildingblackwealth.htm

Brown, M. (2022, April 9). Then and now. Black Voice News. Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://blackvoicenews.com/2022/03/09/black-californians-move-voter-momentum-down-ballot-for-lasting-change/

California Reinvestment Coalition. FDIC. (2022, August 4). Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.fdic.gov/resources/regulations/federal-register-publications/2022/2022-community-reinvestment-act-3064-af81.html

Cornell Law School. (n.d.). Redlining. Legal Information Institute. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/redlining#:~:text=The%20term%20redlining%20finds%20its,the%20wake%20of%20the%20Depression.

Crvrdo. (2021, September 16). Decennial census P.L. 94-171 redistricting data. Census.gov. Retrieved February 21, 2023, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/about/rdo/summary-files.html

Diamond, A. (2018, October). The original meanings of the “American Dream” and “America first” were starkly different from how we use them today. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/behold-america-american-dream-slogan-book-sarah-churchwell-180970311/

Gorman, T. (1994, January 12). Column one : Bad Times for a boom town : In the ’80s, Moreno Valley was a model of affordable, if remote, suburbia. then came the recession. Today, rocked by foreclosures and dashed hopes, the city tries to regain its balance. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 19, 2023, from https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-01-12-mn-10930-story.html

Greene, D. (2018, November 27). Why real estate builds wealth more consistently than other asset classes. Forbes. Retrieved February 22, 2023, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/davidgreene/2018/11/27/why-real-estate-builds-wealth-more-consistently-than-other-asset-classes/?sh=92d0f5954056

Gudis, C. (2022, September 25). Claiming Our Space. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e441b082dd8646cfa48fd5017730e7e9

History of fair housing – HUD. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). (n.d.). Retrieved February 15, 2023, from https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/fair_housing_equal_opp/aboutfheo/history#:~:text=Title%20VIII%20of%20the%20Act,enough%20majority%20for%20its%20passage.

Jargowsky, P. A., Ding, L., & Fletcher, N. (2019, August 19). The Fair Housing Act at 50: Successes, failures, and Future Directions. Taylor & Francis. Retrieved February 27, 2023, from https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/10511482.2019.1639406#:~:text=harassment%2C%20and%20evictions.-,Success%20or%20Failure%3F,%2C%2040%2C%201%E2%80%935.

Johnson, J. (2022, June 30). Subprime mortgage. The Balance. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://www.thebalancemoney.com/what-is-a-subprime-mortgage-5248854

Justice Department announces New Initiative to Combat Redlining. The United States Department of Justice. (2022, July 6). Retrieved January 27, 2023, from https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/justice-department-announces-new-initiative-combat-redlining

Langley, B. (2023, February 10). Yolanda Moses: Move from Compton to Perris. personal.

Langley, B. (2023, March 28). Candice Mays: Living in Moreno Valley. personal.

Langley, B. (2023, March 15). Rose Mayes: Move from Compton to Perris. personal.

Langley, B. (2023, March 30). Billy Ross: SubPrime Loan Crisis. personal.

Legal Information Institute. (n.d.). Redlining. Cornell Law School. Retrieved January 26, 2023, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/wex/redlining#:~:text=The%20term%20redlining%20finds%20its,the%20wake%20of%20the%20Depression.

March Air Reserve Base. About Us. (n.d.). Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.march.afrc.af.mil/About-Us/

Martin, E. J. (2023, February 8). What is redlining? an overview of America’s legacy of racism in real estate. Bankrate. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.bankrate.com/mortgages/what-is-redlining/#redlining-affect-on-real-estate

Martinez, E., & Glantz, A. (2018, February 18). Modern-day redlining: Banks discriminate in lending. Reveal. Retrieved February 24, 2023, from https://revealnews.org/article/for-people-of-color-banks-are-shutting-the-door-to-homeownership/

Master, R. (2022, April 7). Modern Day Redlining. Juris Magazine. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://sites.law.duq.edu/juris/2022/04/07/modern-day-redlining/

Mejia, M. C., Johnson, H., & Lafortune, J. (2023, March 6). California’s housing divide. Public Policy Institute of California. https://www.ppic.org/blog/californias-housing-divide/

Moreno Valley Population. World Population. (2019). Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://www.populationu.com/cities/moreno-valley-ca-population

Moreno Valley. Moreno Valley – Place Explorer – Data Commons. (2021). Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://datacommons.org/place/geoId/0649270?utm_medium=explore&mprop=count&popt=Person&cpv=race%2CBlackOrAfricanAmericanAlone&hl=en

NFHA. (n.d.). Legal framework: Redlining violates the Fair Housing Act and the equal … Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://nationalfairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/Topic-2.pdf

PatientEngagementHIT. (2022, July 6). Redlining continues to impact cardiometabolic risk, health disparities. PatientEngagementHIT. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://patientengagementhit.com/news/redlining-continues-to-impact-cardiometabolic-risk-health-disparities

Perry, A. M., & Harshbarger, D. (2022, March 9). America’s formerly redlined neighborhoods have changed, and so must solutions to rectify them. Brookings. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.brookings.edu/research/americas-formerly-redlines-areas-changed-so-must-solutions/#:~:text=The%20practice%20of%20redlining%20was,same%20manner%20as%20Black%20residents.

Press, D. (2018, September 14). How the federal government created the Subprime Mortgage Crisis: Daniel Press. FEE Freeman Article. Retrieved February 25, 2023, from https://fee.org/articles/how-the-federal-government-created-the-subprime-mortgage-crisis/

Reducing the racial homeownership gap. Urban Institute. (n.d.). https://www.urban.org/policy-centers/housing-finance-policy-center/projects/reducing-racial-homeownership-gap

Redlining and neighborhood health ” NCRC. NCRC. (2021, October 12). Retrieved February 25, 2023, from https://ncrc.org/holc-health/

Riverside, CA. Data USA. (2019). Retrieved April 28, 2023, from https://datausa.io/profile/geo/riverside-ca

Rugh, J. S., & Massey, D. S. (2010, October 1). Racial segregation and the American foreclosure crisis. American sociological review. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4193596/#:~:text=Compared%20to%20whites%20with%20similar,et%20al%202005%2C%202007)

San Bernardino population. World Population. (2019). Retrieved April 14, 2023, from https://www.populationu.com/cities/san-bernardino-ca-population

Spencer, R. J. W. (2021, March 6). Blaxit: An exodus in Los Angeles. Ark Republic. Retrieved February 20, 2023, from https://www.arkrepublic.com/2019/10/01/blaxit-an-exodus-in-los-angeles/

Swope, C. B., Hernández, D., & Cushing, L. J. (2022, December). The relationship of historical redlining with present-day neighborhood environmental and Health Outcomes: A scoping review and conceptual model. Journal of urban health: bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. Retrieved February 28, 2023, from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9342590/#:~:text=Redlining%20thereby%20contributed%20to%20segregation,health%20and%20health%2Drelated%20outcomes.

Tanouye, M. (2021, March 4). Redlining in Riverside. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved February 21, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/8d5c935659954cfa83861bb20a8cb278

Tilton, J. (2022, October 20). Building a movement on San Bernardino’s Westside. ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved April 20, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/e2431587394f4f19b1afd4221881fa20

Tilton, J., Gomez, D., & Costello, M. (2022, November 30). Fighting School segregation in San Bernardino. Fighting School Segregation in San Bernardino. Retrieved December 10, 2022, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/13d98519b5e2499fa4c6c9eaf606c585

Tilton, J. (2023). Color lines in San Bernardino: Mapping Housing Segregation on San Bernardino’s Westside. Retrieved January 13, 2023, from https://storymaps.arcgis.com/stories/cc8794c1eb9041f48b9f43f929841c56

U.S. Federal Housing Finance Agency, All-Transactions House Price Index for Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA (MSA) [ATNHPIUS40140Q], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/ATNHPIUS40140Q, February 28, 2023

Centerpoint: The Thick Red Line

Part 1: The Line Begins Here: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire

Part 2: The Line Runs Through Here: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire

Part 3: Lines Keep Extending Through Times: A History of Redlining in Southern California’s Inland Empire